Policing black women’s hair

The policing of black hair often begins at a very young age, in the most subtle and intimate spaces, long before you get to school.

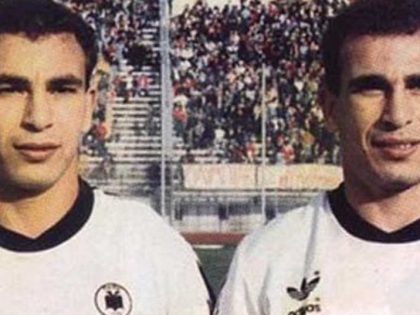

Angela Davis meets Zulaikha Patel, the student at the lead of the protests at Pretoria Girls High in September 2016. Image credit Leila Dee Dougan

The thickness and texture of my black hair was under constant scrutiny when I was a child. My aunt used to call me bossiekop (from the Afrikaans, meaning bushy head). The kids at school would use terms like Goema hare (candyfloss hair) and kroeskop (fuzzy head). My cousin would joke: “You can’t even put a comb through your hair.”

Black women’s hair was big news in South Africa earlier this month as protests at South African schools across the country saw brave young women stand up against racist policies in the various ‘codes of conduct’ enforced in their places of learning. The demonstrations at middle class, Model C (former whites-only public) schools like Pretoria Girls High, Sans Souci in Cape Town and Lawson Girls High School in Nelson Mandela Bay – all schools where the students are mostly black and the teachers mostly white – were about much much more than hair, but these protests spoke to our roots as a site of struggle, and a route for resistance.

The policing of black hair often begins at a very young age, in the most subtle and intimate spaces, long before you get to school. I hated when my mother “did” my hair. From a young age I knew the hairdryer wasn’t hot enough and the rollers not tight enough to tame my curls. I knew the brush she was using would never leave me with hair straight enough to flick back, or cut a fringe.

My sister and I would sit between my mothers legs. Her on the couch, us taking turns on the pillow at her feet. Armed with a hairdryer and a brush she would pull and tug at our scalps, trying her best to get it “manageable.” My hair would turn out big. Just big. A huge soft afro that was long enough to tie back for school, but nowhere near “tame” enough to delicately shake off the shoulder.

When my mother was done with my hair I would stand in front of the mirror in the room I shared with my older sister, look at my reflection, and cry. I felt so ugly and so helpless with my afro. I knew that my mother could never make me look like the white women in the shampoo adverts. It was only the aunties at the hairdresser who had all the right tools to “fix” my locks.

I have more memories of the hairdresser down the road than I do of nursery school. I must have been as young as five when the women with the dye-stained apron, hair clips gripped to the bottom of her t-shirt, would stack white plastic chairs at the basin so that my head could reach the sink. My neck would ache in the basin dent, the water would always be either too hot, or too cold and the hairdressers’ vigorous shampoo scrubbing would make me dizzy. The rollers were always too tight, the hair pins would be jabbed into my tender, young scalp and the hour sitting under the hot dryer felt like a lifetime.

No one understands the phrase “pain is beauty” like a young black girl who has just been to the hairdresser. And after all that pain I would indeed feel beautiful. I had long, straight hair that I could leave loose, flick and comb through. But it was temporary. My hair would “last” for a mere two days, more specifically, my hair would “last” until school swimming lessons on a Wednesday.

Throughout primary and high school, the code of conduct stated that hair should be “neat,” and is just one example of the many way these institutions, which have their own roots firmly growing from our colonial history, govern not only children but also parents. The outdated and outright racist rules were something our parents tolerated during term time, but over school holidays our curls were left to grow.

Summer holidays would be spent at my cousins house in Atlantis, about an hour from downtown Cape Town. They had a caravan, a massive garden and a huge swimming pool (our favorite). We would swim until our feet and fingers turned rubbery. Our eyes would turn blood red from the chlorine, and we would lie belly-down on the hot bricks to warm our shaking bodies before jumping back in to the freezing cold water. Those were days of Kreol chips, fizzers and two-rand coins pushed into your palm by an adoring aunty or uncle for a Double O soft drink. Bompies (frozen juice) and sugary bunnylicks (ice lollies) would leave your tongue rainbow green, red or orange. But most importantly, they were days of afros, when parents rarely fought the tangles (there was really no point considering we spent most of our time in the pool) and left our hair to it’s natural state because there was no “code of conduct,” no threat of punishment.

The joy of swimming, and bunnylicks and afros was limited to school holidays. During term time swimming would more often than not be followed by tears. I recall my aunt sitting on the edge of the bath and pulling at my cousin’s long, mousy-brown hair as she sat in a tub of amateur alchemy. Everything from whiskey to egg was sworn by to nourish and soften. Half-used jars and tubs of the latest conditioners, oils and moisturizers would line the windowsill above the bath like ammo, a site of battle between mother, and daughter’s curls, all for the sake of looking “neat.”

My white friends hair always looked neat and they didn’t know the amount of time it took, or the pain I had to endure to get my hair looking like theirs. They would plait each others thin, blonde strands while I looked on with envy. After swimming their hair would dry “perfectly” whereas any form of humidity or moisture was my nemesis. Anything from shower steam to a light mist was enough to provide extreme levels of anxiety about whether my hair would “mince” or “go home.”

By that point my curls were long internalized as a mark of shame, and what I was expressing on the outside had much to do with how my hair was managed within the home and at school. A prime example was weekend family gatherings. You see, in my family, Sunday lunch would always be followed by “Sunday hair” in order to get ready for the week ahead.

As the aunties washed the dishes and the uncles read their newspapers waiting for tea at five (I shake my head thinking about the gender norms enforced through mundane family rituals, but that’s for another time), the cousins (all girls), had our own rituals. Relaxer would be followed by curlers, blow drying and a swirlkouse, which would leave the room hot, and smelling like product and burnt hair.

With the money I earned from my first job, for instance, I bought a large hairdryer, rollers and an assortment of round brushes and as a teenager I saw these tools as allies. It was only at university that I threw them all out.

Reuniting with my curls was less a conscious decision to rebel against the system of whiteness that taught me self-hate, and more about being free from the pain of curlers, the dizzying heat from the hairdryer and the hours spent fighting what naturally grew from my head (I would “blow out” my hair almost three times a week, it would take as long as three hours a time).

But of course you’re not free from the arrogance of whiteness once you’ve taken this route. Since going natural I’ve had numerous instances of my hair being touched, patted and pulled at by strangers (mostly white women), who’ve called it “exotic,” have compared it to a pineapple and referred to it as “surprisingly soft.” Hairdressers tell me that they don’t do “ethnic hair” and an Australian tourist once grabbed onto my curls and said “It’s like a sheep” before turning to her husband to say “go on, touch it, she won’t mind.”

To this very day, my grandfather will pass comments before the Rooibos tea has even been poured “Leila, what’s happening to your hair, why don’t you brush your hair?” Why is black hair such a threat?

Thinking back to those Sunday hair sessions, above the hum of the portable hairdryer, we laughed, we shared secrets, we gossiped, we spent time. Isn’t that the real beauty when it comes to black women’s hair? The ritual between sisters, mothers and daughters, spending time and passing down knowledge. Why were we not styling afros and dreads, why not twists and braids, cornrows and locs?

Every black woman has their own stories about their hair, their curls and societies endless need to tame, manage and straighten whether at school, in the home, or both. But the young black women who used their natural hair as a form of protest this month have clearly stated that they will no longer tolerate the racist frameworks, formal and informal, that teach them self-hate.