How much does a Nigerian intellectual cost?

The country that once produced some of Africa’s fiercest moral voices now struggles to sustain independent thought.

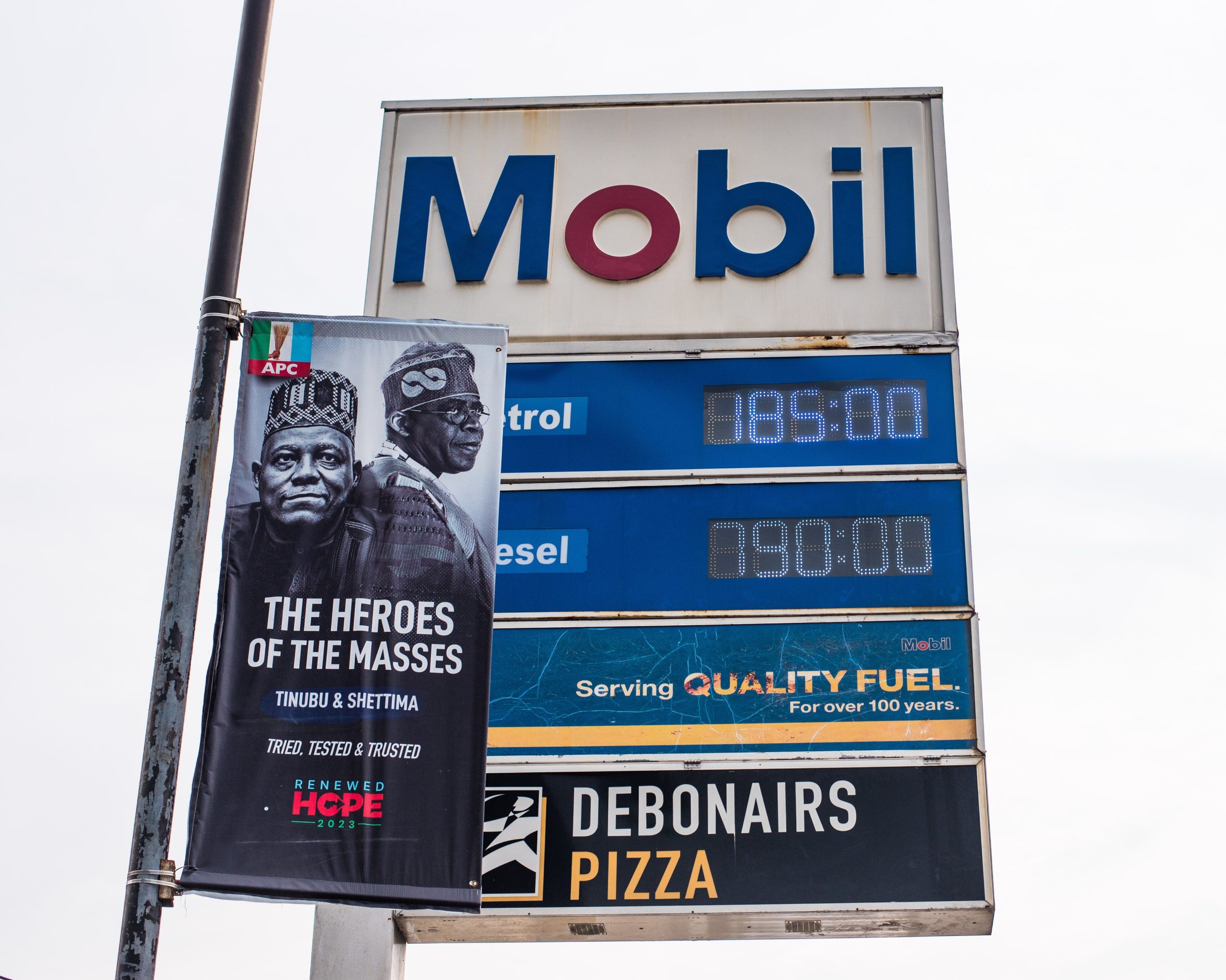

Lagos. Image credit Tolu Owoeye via Shutterstock © 2023

In the early 2000s, during one of the prolonged strikes of the Academic Staff Union of Universities that shuttered Nigerian campuses for months, I encountered an essay in the Nigerian Tribune that challenged my understanding of literature’s place in the world and the mediating power of language. The article, written by the late Abubakar Gimba, examined the government’s criminal neglect of the education sector while also appealing to striking academics to consider the children caught in the crossfire of institutional failure.

I was deeply drawn by the architecture of his argument. The way his prose moved from indictment to appeal without sacrificing its intellectual honesty; literature as a kind of surgery on the body politic, painful but necessary, demanding that we confront uncomfortable truths about ourselves and our society.

I came to literature through writers who understood that in societies still bleeding from the wounds of colonial extraction, one of the writer’s key obligations was to serve as witness, agitator, and keeper of the collective memory, a generation of intellectuals who refused to accept that independence had been achieved merely by the lowering of one flag and the raising of another.

From the anti-colonial pamphleteers of the 1940s to the Newswatch generation, Nigeria’s intellectuals once stood between citizen and state like unpaid sentries. Dele Giwa lost his life to a parcel bomb in 1986; Ken Saro‑Wiwa lost his to Abacha’s hangman in 1995. Between 1994 and 1998, hundreds of writers, editors, and organisers slipped through the borders to escape Abacha’s bloodlust. The National Democratic Coalition (NADECO), formed in May 1994, was the fulcrum of exile politics. Wole Soyinka, Anthony Enahoro, Ayo Opadokun, and others carried the struggle from London basements to Capitol Hill hearing rooms. Within this matrix was Bola Ahmed Tinubu, a fugitive senator with deep pockets and deeper ambitions.

Depending on who’s telling it, Tinubu was either a hero of Nigeria’s democratic struggle or a successful Third Republic politician whose financial contributions earned him proximity to the moral glow of exile politics and helped launder his credentials.

According to NADECO lore, Tinubu, who had fled Nigeria through a hospital window in those heady days, became a source of financial succor to the movement’s exiled group of intellectuals and activists: trading rice with Taiwan to support the cause, in Soyinka’s telling; contributing to the purchase of the transmitter that powered Radio Kudirat, the pirate station that rattled the junta at large. Political exile makes for complicated bedfellows: Trotsky once found himself dependent on the hospitality of bourgeois democracies he had spent his life denouncing; the ANC in exile accepted funds from Scandinavian governments and multinational unions with their own interests to protect; Ho Chi Minh collaborated briefly with the American OSS against Japan. Sometimes the geography of the struggle blurs conviction and convenience.

Tinubu returned to Nigeria following the restoration of democracy in the late 1990s as a hero, Saul among the prophets. His NADECO aura played no small part in his ascension to the governorship of Lagos State. When Chief Anthony Enahoro returned from exile in 2000 to a reception hosted in Lagos, Frank Kokori, the respected unionist and stalwart of the pro-democracy struggle, remarked:

What I told Pa Enahoro in America has today come to pass. Revolutionaries must have a base. We don’t just boycott the political process. If Tinubu does not reign (as governor) in Lagos today, we would not have been able to give Pa Enahoro this kind of rousing welcome…

More than two decades later, when Tinubu was elected President after the 2023 elections, a columnist writing for the Vanguard described it as, “a reward for NADECO, June 12 struggles.”

Yet the story of NADECO reveals the deeper pathology that would eventually consume Nigeria’s oppositional culture. The same individuals who once organized against military dictatorship would later become architects of the very system they had once opposed: radicals turned governors, columnists turned presidential advisers. Reuben Abati swapped The Guardian’s back page for Aso Rock’s briefing room; Femi Adesina would do the same under Buhari. The title “Special Adviser on Media and Communication” became Abuja’s gilded quarantine for former scolds.

Meanwhile, the lecture halls that produced earlier generations of intellectuals and visionaries have progressively declined. Over the last quarter-century, Nigerian universities have been closed for nearly 1,600 days, equivalent to more than four academic years, due to ASUU strikes. Even when classrooms reopen, they do so on starvation rations: the 2024 federal budget allotted barely 7% to education, less than half of UNESCO’s recommended floor.

Tinubu’s evolution, from NADECO financier to one of Nigeria’s most powerful political godfathers, represents the systematic and structural transformation of opposition into complicity. More than any of his contemporaries, he grasped the psychological economy of power and had a practised instinct for making even his opponents dependent on his largesse. What has emerged under his watch is a sophisticated system in which intellectuals, clergy, thugs, and politicians alike have been drawn into a single patronage network whose gravitational pull is so strong it now defines the political horizon itself. At least five governors from the opposition party and a retinue of state and federal legislators have recently defected to the ruling APC, marking a near-perfect consolidation of a decades-long project of converting dissent into property. The Nigerian state, having learned from the Abacha years that direct repression generated too much international attention, developed more sophisticated methods for neutralizing opposition. Instead of killing intellectuals, it began buying them.

Still, for clarity, we must expand our lens beyond individuals and consider structure. That the post-colonial state in Africa inherited its colonial borders along with the colonizer’s extractive psychology has been rigorously observed. The unfortunate archetype of nationalist intellectuals, who once promised liberation, has been thoughtfully drawn out, separately, by Fanon and Cabral, as the transmission line between the nation-state and a predatory bourgeoisie. Yet Nigeria’s variant of this tragedy is intensified by its peculiar history of dehumanisation.

The British did not so much govern Nigeria as manage its competing interests and contradictions. To the colonial authorities, Nigerians were resources, measurable in tonnage, taxation, and labor. The moral questions of citizenship and belonging were ceded to the new political elite who inherited the machine. What ensued, predictably, was an existential scramble for positioning. The government became a factory for privilege, and ordinary Nigerians were the raw material it consumed.

The deeper tragedy lies in how this extractive order deformed the moral imagination. Few governments in human history have treated their citizens with as much disdain as the Nigerian government. The people have been literally made to eat shit and say thank you while at it. In a society where the state’s primary function is predation over protection, the people have learned to survive through mimicry: by bending rules and currying favour, shamelessly cultivating proximity to power, a Darwinian survivalism that has since hardened into culture.

This is why the Nigerian obsession with status and the bloated sense of self-importance should not be mistaken for mere vanity. It is a kind of self-defence, a desperate performance of worth in a system that recognizes only power and indexes your humanity to wealth. To be poor is to be invisible. And so, every act of corruption, every betrayal of principle, every silence purchased with a contract or appointment, is animated by a quiet terror: the fear of returning to nothingness.

It is from this context that the contemporary Nigerian intellectual class emerges, more mirror than counterforce, fluent in critique, yet complicit in the very hierarchies they diagnose. To speak truth to power has become less a civic duty than a career strategy. Nigeria’s sheer size, its violent fusions of ethnicity and religion, and its oil wealth have all intensified the collapse of trust between citizen and state. The result is a moral economy where the vocabulary of value has been inverted: wealth without work, faith without ethics, intellect without integrity.

Under this dispensation, the intellectual who maintains principled opposition to corruption is seen as naive or, worse, unsuccessful. The writer or journalist who refuses to sell their platform to the highest bidder is viewed as lacking business acumen. The academic who turns down lucrative government consultancies to maintain their independence is considered foolish rather than principled.

Nowhere are these issues more evident than in the approach to political engagement. What was once a testing ground for ideas and ideals has since degenerated into another avenue for personal advancement. The phrase “politics is not a do-or-die affair” has been weaponised to justify the most cynical forms of opportunism, as if treating politics as a matter of life and death were somehow primitive rather than an appropriate response to systems that literally determine who lives and dies.

When former critics become government apologists, the very language of accountability becomes corrupted. Citizens lose the ability to distinguish between propaganda and analysis, between genuine reform and cosmetic changes designed to manage public perception. This has created more than a crisis of interpretation in Nigerian public life.

The absence of intellectuals capable of articulating a hope grounded in serious analysis and concrete possibilities has left Nigerians vulnerable to both despair and false prophets. Within a single generation, a tradition that had produced some of the world’s most powerful voices for justice and human dignity has been largely destroyed. The country that gave the world Achebe’s moral clarity and Soyinka’s righteous fury now struggles to produce intellectuals capable of sustained critique of even the most obvious failures.

The digital revolution, which might have democratized access to information and expanded platforms for dissent, has, instead, accelerated the degradation of public discourse. Social media platforms that could have served as modern equivalents of the newspaper columns where intellectuals once published their critiques have become echo chambers of misinformation and tribal antagonism.

The Occupy Nigeria crowd of social media agitators, who contributed significantly to hounding Goodluck Jonathan out of office, have also found plush jobs in government or found themselves close enough to leverage influence for personal ends. The space that figures like Abubakar Gimba once occupied, characterized by thoughtful, nuanced, and morally serious engagement with public issues, has been replaced by performative outrage and simplified sloganeering that digital platforms reward.

Any counteracting effort, beyond nostalgia for a golden age that may have been less golden than memory suggests, must begin with a recognition that intellectual independence cannot be sustained in conditions of economic desperation. Where rent is unpaid and children go hungry, the space for moral courage inevitably collapses into the daily arithmetic of survival. Nothing that can be said about integrity will hold if the social structure rewards sycophancy and punishes honesty. Nigeria’s unending cycle of poverty and precarity can be effectively seen as an instrument of control that renders citizens docile through exhaustion.

But what is made can be unmade. The search for a just society has not been abandoned. The moral voice has become itinerant, diffused into new forms across non-traditional routes; data collectives pushing for transparency, feminist movements with unrelenting civic courage, satirists, independent presses, and citizen archives. A new civic imagination is struggling to assert itself. It is imperfect, fragmented, and often co-opted, but the work of re-establishing a baseline for shared ethical imagination continues. The #EndSARS protests revealed a generation’s rage and its longing for dignity, a demand for accountability rooted in the simplest of civic rights: that a citizen’s life should count. Despite the fresh wave of migration it triggered after it was crushed by the Nigerian military, ghosts of its discontent still linger.

Yet moral renewal cannot rely on outrage alone. It will require the deliberate rebuilding of the intellectual and imaginative infrastructure that allows a people to see themselves truthfully. For all the failures of the state, the imagination remains the one institution the powerful cannot fully capture. It is there, in the stubborn work of writing, teaching, organizing, and making, of refusing to be silenced or bought, that moral authority can be rebuilt. In classrooms kept alive by teachers who refuse despair; in newsrooms that still risk integrity for accuracy; in reading collectives, film labs, community libraries, and digital platforms that prize inquiry over impression.

As with everything else that ensures their continued survival, Nigerians must, on their own, continue the slow restoration of conditions in which knowledge can exist for its own sake, untethered from the demand for utility. They must lean further into new forms of patronage and community, networks of solidarity that enlarge interiority: citizen-funded art spaces, regional residencies, literary festivals, and community gatherings that nurture the life of the mind. These are the laboratories where the moral imagination must again come alive.

Whether these efforts can overcome the internal and external fissures that contend with Nigerian life and coalesce into a critical and functional mass is a question that time alone can answer. What is certain is that without them, Nigeria will continue its descent into moral and intellectual darkness, making genuine development impossible. The choice, as always, is between the easy path of accommodation and the difficult, necessary work of building alternatives.