Mapping Johannesburg’s wounds

In his latest exhibition, Khanya Zibaya charts the psychic and spatial terrain of a city where homelessness, decay, and human resilience sit uneasily together.

"We Should All Be Dead" exhibition in Cape Town. All images courtesy Vela Projects.

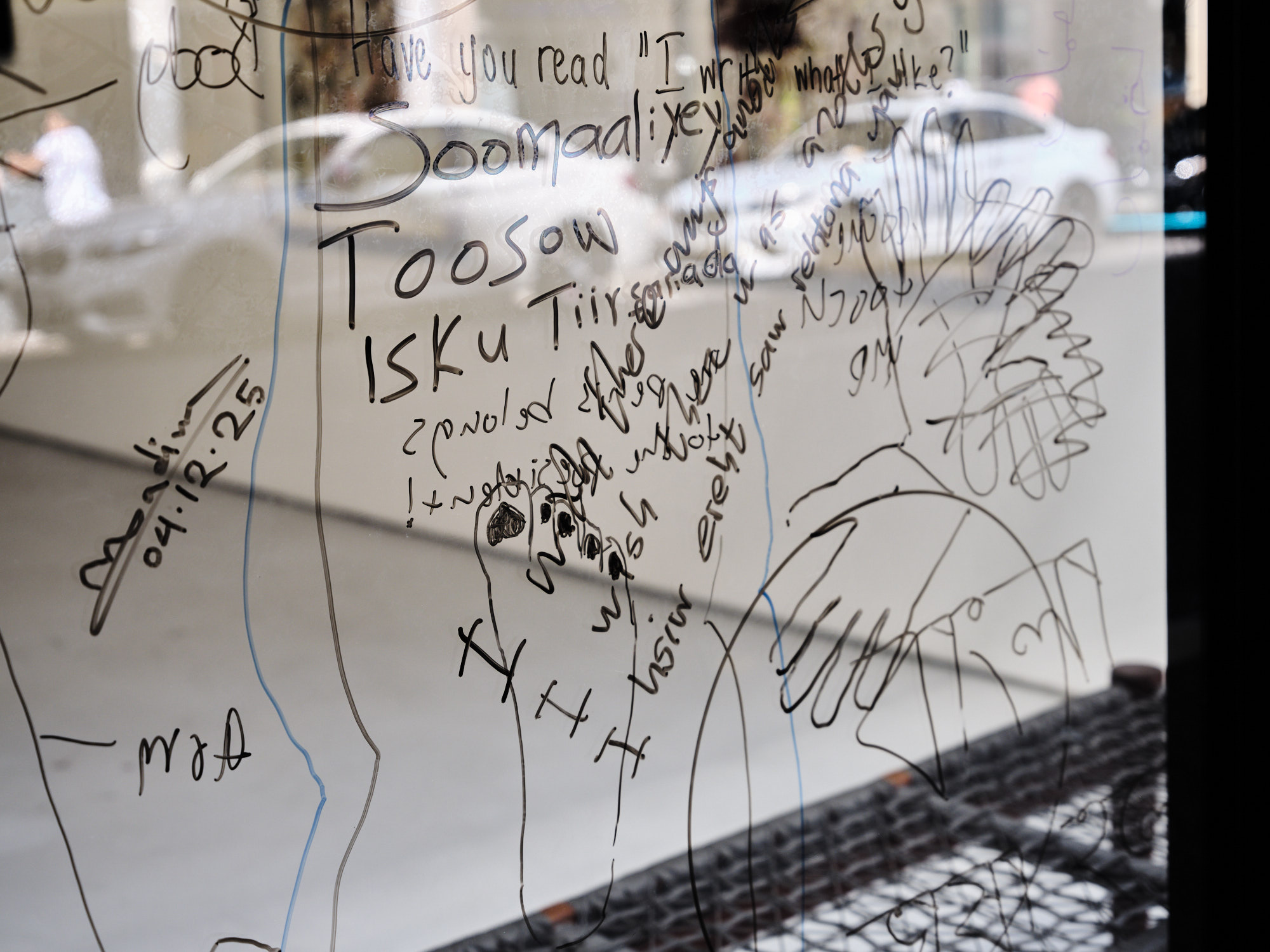

In his solo exhibition, ominously titled “We Should All Be Dead,” Eastern Cape–born and Johannesburg-based artist Khanya Zibaya charts and interprets the hidden social and spatial anomalies that shape everyday life in Johannesburg. Moving ambidextrously between photography and paper collage, Zibaya fixes his gaze on the city—a boundless metropolis rife with contradictions, both humane and grotesque. Johannesburg is a city of contrasts. On one hand, “Jo’burg,” as it is affectionately known, is celebrated as Africa’s bustling economic epicenter; on the other, it is notorious for high crime levels, pervasive violence, and creeping infrastructural decline. In his presentation at Cape Town’s Vela Projects, Zibaya meditates on these polarities by constructing a visual field of artistic analysis composed of fragments drawn from the lived experiences of the city’s most vulnerable inhabitants

A concrete metropolis where the dreams of many are both realized and trampled upon, Johannesburg is small in geographic size but larger than life in its continental and global stature. It is, indeed, a city of complexity. The city is cloaked in an urban mythology, rooted in the economic and political significance it gained following the discovery of gold in the region in the late 1800s. This phenomenon birthed numerous industries in the city and its surroundings over successive generations, fostering Johannesburg’s enduring reputation as a destination for those seeking upward mobility. Consequently, large numbers of people have relocated to the city and its adjacent areas in search of employment and the promise of a better life.

Societies emerging from conflict, such as South Africa, carry deep-seated psycho-social traumas rooted in their past. These scars are embodied by their people, persisting in both their minds and future aspirations. Despite the mechanisms implemented by the post-apartheid state to redress past injustices, there has been minimal rupture between the past and the present. The detritus of the country’s painful history is evident across all spheres of South African society, embedded in the scaffolding of social and public spaces and stretching across both rural areas and metropolitan landscapes.

Like many of Johannesburg’s inhabitants, Zibaya comes from elsewhere. He migrated to the economic capital from his hometown of Sikote in Tlokoeng, having grown up moving from one orphanage to another. Upon resettling in Johannesburg, Zibaya encountered a new and unfamiliar world, becoming a stranger in his newfound home. Having had a nomadic upbringing, Zibaya is intimately familiar with this sense of estrangement from his surroundings—an acute experience of solastalgia, the feeling of homesickness while still at home. For Zibaya, home is a shifting target, making him not a typical stranger; he is the kind of stranger who is unusually familiar with, and intimately aware of, the opaque predicaments that must be navigated in his new home. This knowledge resides quietly within him—and, in fact, occupies the recesses of many South Africans’ minds, shaped by the realities we share as inhabitants of this country. At one period in history, South African cities were segregated spaces; following the country’s political transformation, these cities had to remould themselves.

Indeed, cities can be understood as organisms, constructed to respond to the ever-changing conditions of modernity. It is therefore not uncommon for inhabitants of bustling cities, such as Johannesburg and many others around the world, to experience moments of dysfamiliarity with their urban surroundings. Cities are terrains that are socio-geographically designed to be mutable, and Johannesburg is one such amorphous city. Zibaya, an attentive inhabitant of this formless metropolis, perceptively uncovers the layered imprints the city leaves upon us. He also uncovers the man-made marks we leave behind in cities and their built environments, revealing traces of our existence within them. There is a profound symbiotic relationship between humans and their environments—a truth as old as human civilization itself. If the spaces we inhabit reflect the human condition, what might Zibaya’s collages and photographic works reveal about us?

Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, in his book Civilization and its Discontents argues that two fundamental drives can explain the phenomena of life. These drives are Eros or the God of love, synonymous with the life instinct, and Thanatos—the God of death, also known as the death drive. Freud’s meta-psychological consideration was not only to enrich the therapeutic process, but he also believed that they would help to critically analyze the individual and societal developments in the bourgeois culture of his era. Although times have changed and culture has evolved, Freud’s theory of drives continues to offer a generative framework for understanding the multiple layers of meaning that shape both the individual and society. I want to use Freud’s theory of drives to understand Zibaya’s presentation at Vela Projects. Considering Freud’s concept of the interplay between the individual and society, we can speculate that societies, whether understood through the collective unconscious that underpins them or the socio-spatial configuration, tend to mirror these dynamics in profound ways.

Freud argues that humans are primarily concerned with their own survival, as members of a species whose continuation is ensured through procreation. The ego and sexual drives are components of Eros: while the ego is oriented toward self-preservation, the sexual drives extend beyond the self, uniting with another to transfer genetic material. Eros, however, is driven by more than the mere urge for genetic procreation. While procreation involves the sexual act, it is also part of a more fundamental and abstract process: the creation of higher unities. Thus, Eros is the drive that continually generates higher unities; it is in this extended form that Eros truly emerges as a fundamental force. This impulse is evident in Zibaya’s work, insofar as the artist seeks to reconstitute his ephemeral recollections of fragments of Johannesburg into consolidated cultural objects of both aesthetic and commercial value. In this process, the notions of creation and survival become legible.

The practice of adorning walls has a long-standing lineage within the Bantu cultural ecosystem. Among the Basotho, for example, women have historically practiced the art of Ditema, an intricate visual language rendered onto the outside surfaces of their homes. This is a rich tradition of symbolic, geometric mural art articulated on the homes of the Basotho, functioning as both aesthetic expression and cultural inscription. This practice is not unique to the Basotho; sub-groups within South Africa’s Bantu-language speaking communities have also long engaged in this decorative tradition. More recently, this aesthetic has been reappropriated within the South African art world, with artists such as Asemahle Ntlonti, Kamyar Binestarigh, and Guy Simpson producing work inspired by walls and the idiomatic exterior features of homes, as well as the interior textures of artist studio spaces.

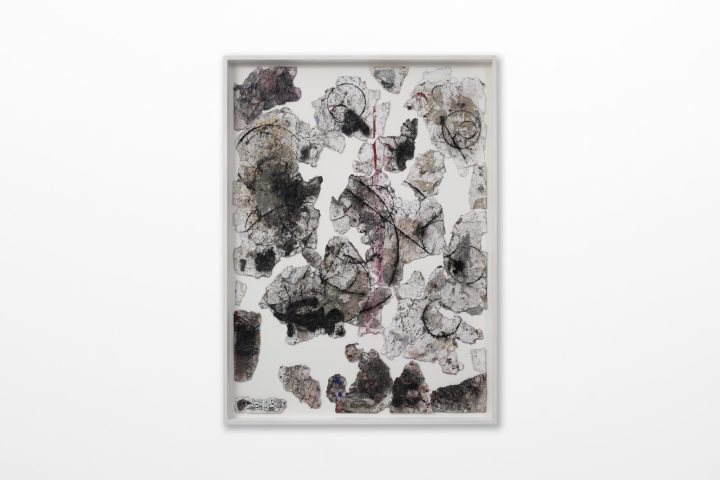

Zibaya states that, in this body of work, he reflects on the ongoing social decay, structural erosion, and spiritual entropy he has observed in everyday life in Johannesburg. He is drawn to the disintegration of the city’s membrane, materialized in the decaying facades of its numerous buildings. Like a surgeon, Zibaya nips and tucks at these walls, aestheticizing the moral, social, and architectural degradation in his striking collages—reproducing the coarse, corroded, and cracked exteriors of Johannesburg’s cityscape. These transmuted surfaces serve as metaphors for the city’s tumultuous status quo and as signifiers of the socio-political, economic, urban, and geographic dissolution affecting segments of Johannesburg. They also evoke the psycho-social trauma endured by its residents.

Zibaya’s work primarily focuses on the lower classes, drawing heavily from his own experiences as a vagabond on the streets of Johannesburg. Lower-class populations, particularly the homeless, are often pushed to the margins of both the city and society at large. Having experienced homelessness in a city as brutal as Johannesburg, Zibaya found himself relegated to a subcategory of citizen—a misfit within the urban landscape. While living as an unhoused member of the city, it is unsurprising that he could only come to know the manifold faces of the buildings from which he was excluded. This is because homeless individuals are deliberately alienated from participating in the urban logics that define what it means to be a “good” citizen, reflecting how Western models of society are often structured around the exclusion of others. In societies structured in this way, political and social systems legitimize themselves through what, or whom, they exclude. Zibaya, like countless others whose bodies populate the streets and pavements like lifeless shadows, was denied access to the protections and shelter offered by urban society.

Rendered obsolete in this sense by the city, Zibaya, a wandering subject, was left without a sense of place or a notion of home. The homeless remain a perennial footnote in the social text of society, particularly in urban areas. As Giorgio Agamben insightfully observes, in Western politics, “bare life” holds the paradoxical distinction of being that which, through its exclusion, constitutes the very foundation of the city of men. The paper collage works, these magnified frames of the artist’s experiences as a displaced body roaming the streets of Johannesburg, demonstrate that the sublime can be encountered in all walks of life. Through the autoethnographic lens he applies to Johannesburg’s brutalist cityscape, Zibaya imparts a coating of dignity to the plight of those marginalized and disregarded by the city. He achieves this through a process that entails the aesthetic sublimation of his own experiences of homelessness, enacted through the production of these collage works. It is noteworthy that Zibaya engages with these cropped representations of isolated architectural elements, transposing them into compelling two-dimensional works of art. Once these works enter the interior of a building—whether an art gallery, a private home, or another space—they are imbued with new meaning, as well as commercial and aesthetic value. The artist’s recontextualisation of these wall abstractions into objects of artistic consumption represents a compelling act of interpolation and transposition.

Returning to Freud, as noted above, the Eros drive is counterbalanced by Thanatos, the death drive. Unlike the drive for survival or self-preservation, Thanatos operates in opposition to it, seeking the shortest path toward decomposition. We know that cities enact a modality of violence on their inhabitants, and this violence happens on various levels. As human-mimicking organisms, cities—when perceived as having human characteristics—can be pushed beyond the egotism that seeks to preserve an internal sense of unity, and instead toward a process that unravels and abolishes such unities. This drive, antithetical to Eros, aims to dissolve these unities and return them to their primordial, inorganic state.

The violence that cities inflict on their homeless is both grotesque and often indescribable. In these spaces, the homeless are stripped of their humanity. It is not the cities themselves that perpetrate this violence, but the human actors who control them. Cities are machines operated by people in positions of power, who enact social, political, and economic forms of violence upon their inhabitants. The homeless are disproportionately at the receiving end of this direct and indirect violence. Like humans, cities unconsciously will themselves toward destruction. This drive toward self-destruction is not accidental; it is an inherent aspect of human existence, and by extension, a fundamental feature of what constitutes a city.

The photographs included in the exhibition offer an expanded articulation of the liminal zones Zibaya traversed during his wanderings through the city. While the paper collages abstractly represent the realities he explores, the images provide a more socio-realist documentation of these spaces. Captured in black-and-white monochrome, the photographs dwell on the familiar scenes one meets while commuting or moving on foot through the city. Shot largely in the soft fade of evening, their atmospheric stillness and observational sensitivity echo the photographic vernacular associated with acclaimed South African photographer Santu Mofokeng. Mofokeng’s photographs illuminate the textures of everyday South African life, moving beyond the stereotypical news images of Soweto that so often fixate on violence or poverty. Instead, through a deeply personal lens, he records communities living in townships and rural areas, capturing religious rituals and landscapes imbued with historical significance, spiritual resonance, memory, and trauma. Zibaya captures similar scenes with a quasi-romantic air, merging the uncertainty that the dark monochrome casts over the imagery with the aliveness of the fleeting moments he memorializes.

Overall, Zibaya’s exhibition at Vela Projects offers a novel account of aspects of city life that unfold on its margins. However, in this context, the edges are internal, deeply imbricated with the core machinations of city life. This is despite the demographic in question, the homeless and lower-class populations, often crudely referred to as the so-called dregs of society who, from a biopolitical perspective, represent some of the most vulnerable and marginalized members of civil society. Zibaya’s artistic perspective blends collage abstraction as a lens into the spatial injustices and socio-political violence inherent in the dynamics of cities. The photographs offer a more intimate encounter with these spaces, and when considered alongside the paper collage works, both can be seen as unconventional forms of cartography, mapping and elucidating the violent spatial realities that exist within the city. Moreover, encoded within these works is a vision of human social space that transcends the predetermined constraints of our current reality—a realm that is more inclusive and no longer a cemetery for society’s outliers, the walking dead.