Djinns in Berlin

At the 13th Berlin Biennale, works from Zambia and beyond summon unseen forces to ask whether solidarity can withstand the gaze of surveillance.

Photo by Alan Alves on Unsplash.

Upon arriving at Heathrow from Lusaka in June, I was met with semi-aggressive cross-questions about my visa and passport from a fellow Muslim hijabi immigration officer. I wondered where her parents and grandparents had traveled from, wanting to return the interrogation and confront her with the irony of our interaction in a country that doesn’t really belong to either of us.

My experience at Heathrow is echoed, if not narrated scene for scene, in Sarnath Banerjee’s work at the KW Berlin. He states that at border control, you are often met with someone who looks like you—a brown or black Other. A “friendly native,” an “informer,” or better yet, a Djinn.

Djinns are invisible beings that live among us. They see us, but we cannot see them. They exist in our homes, commutes, cities, and streets. The Djinn in Sarnath’s comic-book style story is a police informer, because after all, “the best way to control a native is by using another.” In the context of the biennale, Sarnath’s character of the Djinn takes shape as the fugitive, the migrant, the deviant, the fox.

Nothing about my experience at Heathrow was postcolonial. Or perhaps that is the reality of postcoloniality: the empire now runs on internalised suspicion. We watch ourselves for them. But indeed, as Sarnath puts it: “nobody wakes up feeling postcolonial in Delhi.” I argue that we cannot talk about “decolonization” and “post-colonialism” when colonization continues to be exercised, yet it is hardly taught in educational, bureaucratic, or immigration systems. How can we talk about decolonization when countries like Palestine, Sudan, or Congo are currently experiencing a form of it? Why does our framework of history continually center the word “colonial”? Does it not give it too much power?

The concept of this thing, unseen, invisible, and feared by the oppressor, continued to resonate through the biennale, especially in the works from Zambia. Out of around 10 artists exhibiting from Africa, three were from my home country of Zambia. In hearing the wailing women from sculptures whose forms borrow from drums, baskets, or stools, Anawana Haloba’s Looking for Mukamusaba – An Experimental Opera presented intergenerational conversations weighted with eerie tension. The transtemporality of matriarchal voices such as Alice Lenshina, Mukamusaba, and Lucy Sichone resound through echoing forms punctuated with textures of copper, horns, and wood. Calling from a threshold we cannot reach, these women who have been wrongly written, repressed, or silenced in Zambian history wail in anger and grief. Devoid of visibility, their existence is recovered in an honorable oral ode.

Both Isaac Kalambata and Bwanga “Benny Blow” Kapumpa reckon with the threshold between tangible and unseen in Zambian traditional beliefs. Practicing traditional healing meant being outcast due to legal and educational interruptions by colonial and religious ideologies. “Benny Blow” modernizes the traditional healer or Ng’aka as “Dr. Bwanga,” who offers advice via a telephone booth. His take on digital divinity and relationship to the “algorithm” offers a futuristic imagination of how to cure 21st-century ailments. Doctor Bwanga’s space reads like a confession booth with a thatched roof and transparent window. But he’s not there. Maybe an algorithm, maybe a fox, maybe a witch.

Bwanga „Benny Blow“ Kapumpa, Doctor Bwanga in Berlin, 2025, installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2025. © Bwanga „Benny Blow“ Kapumpa; image: Eike Walkenhorst.

While “witch” might read as evil, Kalambata redeems the term, making visible how the colonial campaign silenced traditional healers in the name of capitalism. His bark cloth works weave text from the 1914 Witchcraft Act to discuss how land occupation disrupted access to healing plants, denying vital ingredients to those who needed them.

This tension between erasure and presence is held tightly in Salik Ansari’s Altar of Absences, which focuses on demolition as state violence. He doesn’t show victims or devastation, but instead paints the machinery of destruction on jagged forms resembling shrapnel. These works jut out like wreckage archives. The aerial image of Gaza, filmed during Jordan’s food-aid drop in August 2025, whispers in the same breath.

Salik Ansari, Altars of Absences, 2025, installation view, 13th Berlin Biennale, Former Courthouse Lehrter Straße, 2025. © Salik Ansari; Sakshi Gallery, Mumbai; image: Raisa Galofr

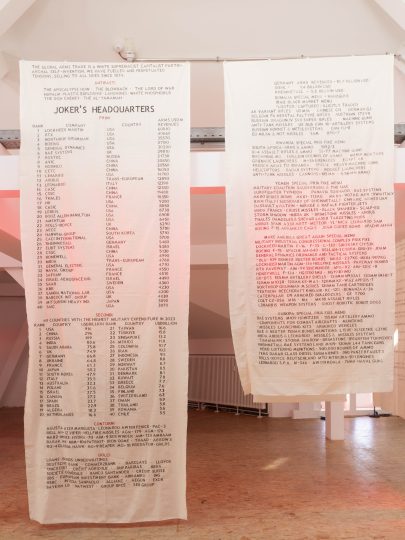

Grupa Spomenik insists genocide is fully speakable but critiques how contemporary forensic science quantifies victims into depersonalized “identified missing persons” devoid of political agency. The Biennale’s cry crescendos with Sawangwongse Yawnghwe’s red-tinted Joker’s Headquarters, which presents evidence quantifying weapons of mass destruction, exposing militaries and nations complicit in arms funding genocides.

What might be read as silence or invisibility in this biennale actually feels like a loud scream trapped in a jar. Allyship and solidarity of artists outside Western art consciousness have been pulled together to acknowledge the plight of Palestine.

Sarnath Banerjee warned against making a “cemetery of dead words.” I worry I’ve done that. What can writing do when Gaza continues to be erased? When solidarity feels like a whisper sealed in a jar? But maybe that whisper matters. Maybe it will crescendo—awakening the Djinn to cross the threshold and finally crack it open.