Angola’s Flash Mobs

Should the tipping point against the MPLA - in power since independence - arrive in Angola, there are some activists ready to hit the ground, running.

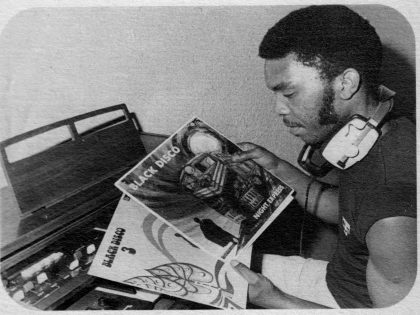

"Luaty Beirão-The Prophets Of Change" by Daniel Arrhakis (2015).

There has been an increase in protest activity across sub-Saharan Africa recently: Burkina Faso’s citizen uprising dominated Africa-focused news outlets and twitter feeds as the president of the country resigned and the military took control of the state; protests also erupted in Togo with citizen calls for constitutional changes in order to bar President Faure Gnassingbe from seeking a third term; and citizens have also taken to the streets in Burundi to voice concerns over the shrinking political space and in DRC to reject any constitutional changes to remove presidential terms. While these countries draw hundreds and thousands of protestors to the streets, a small group of pro-democracy activists in Angola mark the success of their movement through a series of five minute protests.

During the past few months, youth activists have been organizing flash mob protests in front of government buildings around Angola’s capital city of Luanda. Like many other countries, Angolan law requires demonstrators obtain a permit. Activists argue that the information is used to arrest them as soon as they arrive at the protest location. Angolan youth have not been deterred however. Instead they came up with the idea of flash mob protests, organized via text message, to draw even just a few moments of attention for their cause before they are arrested beaten and dragged away by police. In a brief interview early Saturday morning, rapper-activist Luaty da Silva Beirão explained, “If our protests were going to be interrupted after just five minutes, why should we comply strictly with permit laws? It is clear that the police use the information about our location to stop us. This is why we decided to use the element of surprise.”

The activists are from a small-scale youth movement, named Central Angola 7311 after the day of the first protest of 2011. An anonymous call for a mass protest on March 7, 2011, at the Independence Square in Angola’s capital city, Luanda, went viral via the Internet and text message. On the day of the rally, police briefly detained all in attendance, including 17 rappers and three journalists of the private weekly newspaper Novo Jornal, who were there to cover the demonstration. The organizers include rappers, intellectuals, and journalists who call for access to higher education and employment, better housing conditions, improved service delivery of water and electricity, and improved democratic institutions. The youth movement has also called for the resignation of President Eduardo do Santos who has been in office for 33 years.

For these activists, each brief protest serves to “erode the machine of the Angolan state.” 71 year old José Eduardo dos Santos has been president since 1979. He remains in office after the country’s 27 year-long civil war. The war began in 1975, immediately after Angola became independent from Portugal. In 2010 dos Santos strengthened his grip on power with a new constitution that ended the need for a direct presidential ballot— the head of the party that wins in parliamentary elections now automatically becomes president.

In the lead up to the 2012 elections, dos Santos faced increasing opposition as youth groups stepped up anti-government protests. The ruling MPLA prevailed in the polls, maintaining a majority in parliament and securing another term in office for dos Santos. Although a limit of two five-year presidential terms has been set in the country, this does not apply retroactively, meaning that dos Santos could remain in the post until 2022.

While the protests remain small and youth activists say, “sometimes we laugh at ourselves and what we call progress,” they know they have made small gains. Since 2011 when youth first started protesting, there has been an increase in smaller, low-level protests throughout the country including civil service workers demanding better pay and working conditions. Most recently, residents of the Lamarão neighborhood in Aracaju, held a protest after a power cut. This view is echoed by Tiseke Kasambala, Southern Africa Director of Human Rights Watch, who states, “What we’ve seen is an intensification in the number of peaceful protests in Angola, as a result of poor governance issues and the poor economic situation and the gross inequalities that exist in the country.” Given Angola’s culture of fear and intimidation, these protests suggest that various sectors among the population are no longer afraid of the regime the way they once were.

Well-known journalist Rafael Marques de Morais notes that the fear is very real, because journalists and youth activists are routinely arrested and tortured—including him. Amnesty International has also accused the Angolan state of torturing and killing opponents and using violence and excessive force to suppress dissent against the government.

Interviews conducted in Luanda in 2013 with 35 activists indicated that youth were in the process of rethinking strategies. One of the primary youth leaders explained, “We learned that we could attract more attention by marching instead of staying in one place. This helped because we were not large in number so we got attention but we also made the population aware of the protest because you know, we’re never on the news.”

These flash mob protests are the latest tool in their arsenal of strategies. Protesters also utilize a network of citizen journalists to document demonstrations and the violent police response in the moments before they are shut down. Beirão explains that the goal of these flash mob protests is break the barrier of fear, inspire others to feel free to protest, and to create spaces for discussion.

Demonstrations in Angola illustrate the importance of considering the social and political context in which activists must struggle to achieve their goals. In Burkina Faso the situation unfolded quickly as thousands of people took to the streets, demanded that Blaise Campaore who was in power for 27 years step down, and within days the situation shifted as the president resigned and the military took control of the state. The protests in Togo are still playing out with citizens and opposition groups calling for a change in the constitution to limit a third run for a man whose family has been in control of the state since for nearly 50 years. The opposition and youth activists in Angola have not been able to gather the masses or topple the MPLA regime; does this mean that the nascent youth-driven protest movement has been a failure? Is there a clear way to determine the success or failure of citizen uprisings?

Angolan anti-corruption journalist Rafael Marques de Morais recently asserted that the Angolan government is tightening the noose around free expression. Given that collective citizen action in Angola is rare and the majority of the population believes they are under government surveillance, these protests can be viewed not only as a success but as the seeds of change in a country that rarely experienced demonstrations before 2011. Protestors are developing the building blocks needed to sustain a citizen uprising: they have a structure and are developing strategies to continue getting the message out and keeping the pressure on even in their current socio-political environment. Should the tipping point arrive in Angola, there are some activists ready to hit the ground, running.