Guinea’s bet on iron ore

A $20 billion iron ore mega-project is reshaping Guinea’s economy and politics, but communities in Simandou say they still lack water, electricity, and accountability.

Simandou mine. Image via Rio Tinto website (Fair Use).

In November, Ibrahima Sory embarked on a trip to southeastern Guinea—a two-day, 800km road journey from the country’s capital, Conakry, to the rugged mountains of Simandou. It was his third and final trip of the year, and as head of operations of the community-impact NGO, Action Mine Guinée, he’d come to collect information on how mining was affecting the towns and villages there and report to the companies concerned.

In his first few days, tension broke out in two of the communities. Young people in Kérouané—where Singaporean-Chinese company Winning Consortium Simandou is mining iron ore from the first two blocks of four holding the world’s largest untapped iron ore deposit—staged a protest against poor roads, lack of portable water and electricity. In Beyla, where the 110km Simandou mountain chain starts, women railed against Rio Tinto, the British-Australian company drilling blocks three and four, for polluting a stream and digging boreholes that don’t produce enough water.

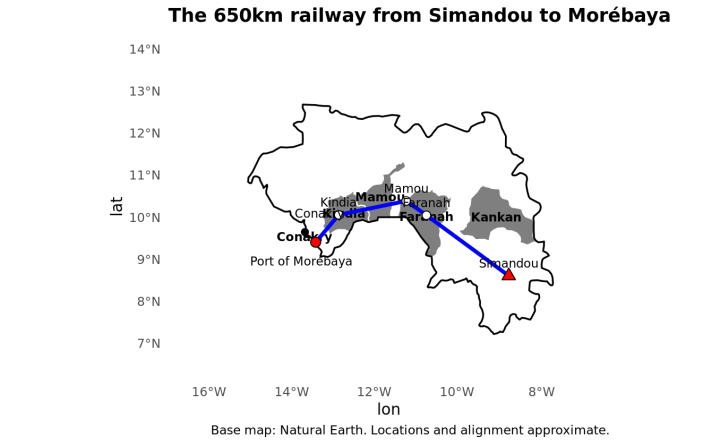

“In the Simandou zone, people are without electricity and water,” said Sory, who mentioned he’d warned Rio Tinto, in one of his policy papers about the water condition in Beyla. “This is what frustrates these communities, who are forced to protest.” The tension flared just days after the inauguration of the Simandou iron ore mine. This $20 billion investment came with a 650km railway and a minerals seaport to export the iron ore, the main component for producing steel. Capital to finance the project came from Winning Consortium and Rio Tinto, with Chinese investors having a greater share.

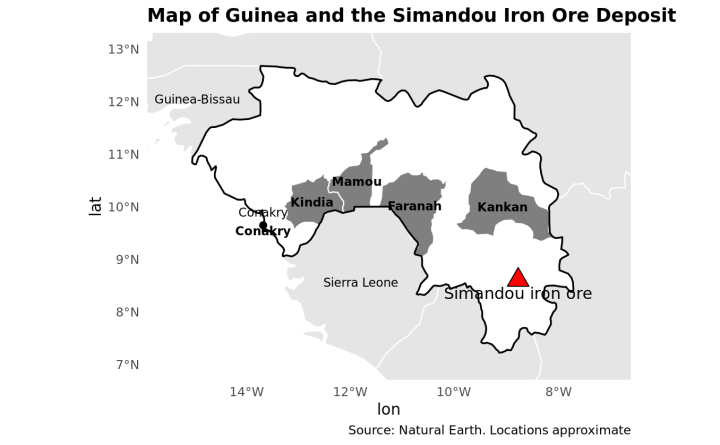

Located in Guinea’s Kankan and Nzérékoré regions—not far from the borders with Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire, Simandou holds 2-4 billion tonnes of exceptionally rich iron ore deposits, with grades hovering around 65.8 per cent, according to S&P Global. When production hits full annual capacity of 120 million tonnes in a few years, Simandou would contribute 3.4 per cent GDP growth to Guinea’s economy by 2039, per the IMF. That would spur investments worth $200 billion, the country’s mining minister Bouna Sylla has said. “We have an opportunity to change the size of our country and the life of our people,” Sylla said.

Guinea’s government, led by military leader General Mamady Doumbouya, wants to use the mine’s proceeds to set up a $1 billion sovereign wealth fund. It’s part of its “Simandou 2040” strategy, a 15-year plan to finance education, infrastructure, and agricultural and industrial projects that would transform the small West African nation of 15 million people. If everything goes well, Guinea will join Botswana and Angola, which have also set up sovereign wealth funds, generated by revenues from diamonds and oil, to shore up their countries against economic headwinds. But experts worry there’s not enough transparency in Simandou, which mirrors management of previous mining booms and casts doubts on whether any promises of infrastructure and a buffer fund will be realized. “[The Simandou] program is rather general,” Sory said, noting that “it doesn’t specify the aspects that will [benefit the] communities [around it].”

Guinea is a top bauxite producer, only second to Australia. Additionally, the country mines significant amounts of gold and diamonds and other precious metals, accounting for 21% of its GDP in 2022 and 90% of its total exports, according to a 2024 World Bank report. The government had set up the Fonds National de Développement Local (FNDL) and Fonds de Développement Économique Local (FODEL), to ensure that proceeds of the mining industry are used for developmental projects across the country, especially in mining zones. But as Le Monde reported in 2019, locals are yet to reap any real benefits from these funding initiatives.

“The first experiences were not good because the [funds collected weren’t] used very effectively,” said Oumar Totiya Barry of Observatoire Guinéen des Mines et Métaux, a Guinean minerals think tank. Barry said Guinea’s military junta suspended the funds when it seized power in 2021; since then, “the communities living in the mining zones are suffering the negative impacts, but they are not directly benefiting from the redistribution of revenues from the exploitation.” He said the government announced last month it would resume FNDL and FODEL operations, but he worried whether there would be any disclosure on the amounts the mining companies have paid into the funds in the past four years.

Barry said good governance is the biggest challenge in the government’s push to use Simandou as an economic driver, as the terms of the contract between the government and its mining partners, Rio Tinto and Winning Consortium, are not sufficiently known, though Jeune Afrique reports the government gets 15% of proceeds from the mine and from the railway, respectively. “The mining sector has suffered a lack of transparency for a long time, often in contracts and payments,” he said.

For ordinary Guineans to benefit from “Simandou 2040,” Barry believes the country’s political institutions will have to be reinforced both at the national and local levels. Guinea’s presidential election is scheduled for December 28, and according to François Conradie, lead political economist of Oxford Economics Africa, General Doumbouya will claim the ballots. “The junta under Mamady Doumbouya has been hostile to journalists and civil society activists—precisely the people who could have been counted on to keep an eye on the management of a sovereign wealth fund,” said Conradie.

General Doumbaya made Simandou, whose development plans started almost three decades ago and was plagued by legal battles and corruption scandals, his top priority after toppling Alpha Condé’s government, when it exceeded its constitutional limit. In 2022, he suspended all activities at the mine, forcing Rio Tinto, which has held mining rights since 1997, to work with Winning Consortium to build the extensive rail line from the Simandou mountains all the way to the western Port of Morebaya. It was easier and cheaper to connect the railway to neighboring Liberia, but Doumbaya’s government insisted on the steel line cutting across the country.

According to the Financial Times, a Guinean lawyer was ordered to slam the door on their way out as a sign of Guinea’s grit when government negotiations with investors got intense. When Winning Consortium acquired Chinese locomotives against General Doumbouya’s advice that they buy them from an American manufacturer, he had them return the units. “Negotiations about Simandou were long and complicated, and I tend to think Guinea got a good deal,” said Conradie. “Chinese firms often pay a bit more for mining assets than their competitors to ensure long-term supply sources.”

Instead of cozying up with the other military rulers in the Sahel region, General Doumbouya has instead found a friend in Rwanda’s pragmatic, yet authoritarian leader, Paul Kagame, who was one of the handful of heads of state present at the Simandou ribbon-cutting ceremony. General Doumbouya could be taking notes from Kagame, credited for putting genocide-scarred Rwanda on a path to economic growth.

The first shipment of the iron ore should be on its way to China. China might have won the race to control global iron ore distribution and steel production, but for Guinea it is an opportunity to leverage the proceeds like Gulf nations, including Saudi Arabia and Qatar, did on oil. However, Barry is cautious. He maintains the country must break with the mindset of earlier mining cycles if it is to achieve more equitable growth. “The mining companies are not there to develop Guinea; they are there for business,” said Barry. “It is up to the state to make very good use of mining revenues to transform governance, political, and economic structures of Guinea.”While General Doumbouya’s government strategizes in Conakry, communities in the Simandou mountains are waiting to see if Simandou’s proceeds will bring meaningful improvements to their lives.