Empty riddles

Drawing on his forced migration from Rwanda, Serge Alain Nitegeka reflects on the forms, fragments, and unsettled histories behind his latest exhibition in Johannesburg.

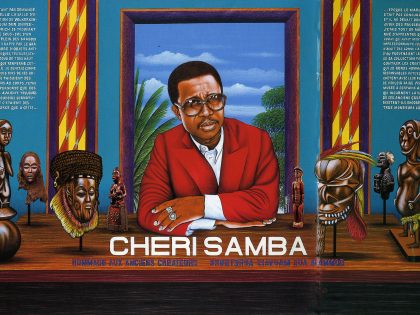

"Identity is Fragile V," Serge Alain Nitegeka (2021). Photo Nina Lieska. Courtesy Stevenson Gallery.

Objects can change as a reflection of how circumstances of the people who carry them do so too. In cases of forced migration, the load is at once physical and psychological. Backpacks, plastic sheets, and duffel bags stretch and take on new forms and textures. These modified objects become adequate to carry personal belongings over long distances. As refugees deal with the immediacy of the journey, negotiate the differences in language, food, weather and the different kinds of obstacles encountered along the way, a sense of uncertainty prevails. It is a labyrinth in which the exit moves all the time, an unstable ground that requires constant adjustment. There is the trauma of the journey, and there is the trauma that led to forcibly leaving in the first place. For artist Serge Alain Nitegeka, who had to flee Rwanda at a young age during the genocide (April – July 1994) first to Democratic Republic of Congo, then Zaire, on foot, “you look at what you can carry and sort of get rid of things you don’t need. It’s a very small list you have to deal with…you know? You have to cut off the excess. And it’s not like you have a lot to cut off, but [you ask yourself] ‘what can I carry with me forever, indefinitely?’ ”

After leaving Rwanda, Nitegeka and his family first stayed in a refugee camp in Goma, then moved to Kenya, and eventually settled in South Africa in 2003, where he studied Fine Arts at Wits University. I had a conversation with him that oscillated between reflections of his recent solo exhibition Black Subjects at the Wits Art Museum (WAM) in Johannesburg, his last fifteen years of practice and what mechanisms he has found to cope with trauma.

Owing to his own life experiences and the effects this continues to have in his creative decisions, Nitegeka believes a lot lies in “dealing with trauma (…) dealing with the experience of having it and having to carry it because it’s one that doesn’t let go of you. It’s something you live with every day. It’s learning how to look at it, configure it to your own personal physique, your own personal abilities.” Something salient was his view on how abstraction and minimalist design can counter the mind clutter as a sanitised language that “denies everything, admits nothing (…) You don’t deal with anything directly. You express yourself in riddles, empty riddles, and you as the author are the one who has the breakdown of what certain forms mean to you.” In essence, abstraction becoming a shield of sorts, an antithesis to exposure.

But no matter how shielded a person is, identity needs work too, because as abstract as this construct might be, it is fragile, it needs maintenance and, the artist argues, vigilance. This is explicitly posed in the self-portrait Identity is Fragile V (2021), but unravelled most interestingly in one of Nitegeka’s most unassuming pieces titled Fragile Cargo from 2010. In our conversation, we spoke extensively about this work; a small sculpture with a piece of bent plywood tightly fitted in a black frame. The three-dimensional frame stands for the conditions that need to happen for something to keep its shape, to be in a particular way. The containment is visible and there is a balanced tension in how the plywood is delicately fitted. “It is about identity over material: how it changes, how it’s forced, how it’s molded, how the environment shapes it… (…) But then that abstraction of identity, how it’s made and how it needs to be maintained was surprisingly very touching to a lot of people that have attended my walkabouts [at WAM]”, shared Nitegeka.

He hadn’t seen the sculpture in more than ten years, and was reunited with it in Johannesburg this year where he “saw it unravelling in front of my eyes the periods I was going there [to WAM]. I had to go and fix it a bit more, sort of put back, because it’s quite resistant. I put it in that sort of cage to keep it the way it was because, on its own, it kept on wanting to snap back into the plywood it was.”

Structural Response V is the latest iteration of Nitegeka’s iconic large scale all-black wooden plank installations that have been widely exhibited in South Africa and overseas. In these installations, visitors are immersed and made to feel small in relation to the scale of the beams that cross above and around them at sharp angles. There is a sense of danger for those who visit the installation. Movement is difficult, but not impossible, echoing the hurdles migrants have to go through as they move from country to country. At WAM, the Structural Response V had a new addition in between the wooden beams: tents lit with a warm light from the inside, giving the impression of occupied spaces. The tents had been previously shown as Camp, a standalone outdoor installation at Nirox Sculpture Park (2025) and Spier Light Art Festival (2025), but never shown as part of the Structural Response. The contrast between the softness of the tents and the hostility of the beams is not only material, it is conceptual. That is, while the beams signal to the hardships of forced migration, the tents point towards a private moment of leisure and rest. These temporary shelters evoke the existence of scenes that the audience does not, cannot, access. Visitors can, however, get close enough to witness that fictional intimacy inside the tents and be part of it as observers.

The artist shared that the tents function as a tool to create a bridge with the audience, as these structures not only refer to the precarity experienced by refugees, but they also signal to other, more joyful, associations with tents: travel, childhood, family holidays, camping and so on. Nitegeka experiments with that overlap between precarity and play in order to get closer to visitors and create what he calls an “audience relatability.” He expanded:

So the idea of camping and its associations in South Africa is a relatable experience. So to have that experience of, you know, joy, relaxation, vacation, family, togetherness (…) and you juxtapose that with displaced people. [You] have a situation whereby you reduce the gap of ‘the other’, ‘the displaced’, ‘the asylum seeker’, ‘the refugee’… You sort of shorten the gap between the host country and the displaced people (…) we all have a kind of common, shared, appreciation to camping or shelter that is a necessity. So on one level, there is an association that’s made, and I think all that goes a long way towards an understanding of tolerance, if you might.

For years, Nitegeka only used black in his work, as this related with central themes in his work such as the uncertainty of the future and the void, but also to his identity as a black man. His choice of materials was intentional from the get go, as he mostly worked with found materials and crates because “they’ve lived in the world, they’ve done things.” Although most of Nitegeka’s works aren’t figurative, the figures that do appear are always the same ones covered in all-black suits. The suits strip away physical features, past experiences and individual identities, rendering the figures anonymous and equal within their shared circumstances. The ‘subjects’ Nitegeka depicts struggling through uneasy paths, pushing against walls, and lifting mended objects could be anyone. As characters of an unfinished story, these figures could be spotted at WAM in the film Black Subjects (2012) and in large scale paintings like Displaced Peoples in Situ: Studio Study XXXVIII (2025). He explained that “the reason for that conceptually, is to put the same people in different environments… that they are moving. There’s this movement: today there are in this painting, then they’re going to end up in a different painting, and they’re going to be in a different environment and landscape. They’re going to be figuring out and in this mess where they, you know, pushing things, they’re trying to organize, and this perpetual, never ending exercise that they’re involved in. They’re in this liminal space indefinitely…”

In 2008, while he was in his third year of Fine Arts at Wits University, Nitegeka rubbed himself with a mix of Vaseline and crushed charcoal. Once fully covered, he jumped inside a crate, closed the lid, hammered himself in and then tried to get out. Because of the charcoal, as he attempted to get out, he left traces of his frantic efforts on the wood. What was later exhibited in the student show were broken crate pieces with imprints of his body, remnants of that performance nobody witnessed. Back then, Serge deliberately subjected himself to difficulty in producing that work, pursuing a type of permanent ‘readiness’ – an impossible task that continues to obsess him. He shared about his rationale:

“The mindset is to be ready, physically, mentally and constantly put myself into the unknown and uncertain positions and see how I respond to sort of learn something about myself…Some of it is quite labor intensive and physically demanding. I think the idea is to have that chosen suffering to prepare myself for the unchosen suffering. I think it’s a counter trauma, sort of self generated response to that. I’ve read up quite a bit about trauma and how different people deal with it, but the one I relate to is the one of physical exhaustion, exertion is a way of living with something. Momentarily check out, but it’s also an affirmation that you’re strong, you know, that you’re not as vulnerable, and that you’re gonna be ready for the next thing.”

In the liminal space between the known and the unknown, adaptability emerges as a necessity. People change in the movement across countries because they have to, and traces of that history are visible: in the body, in the adoption of new cultures and languages, and sometimes even in weary rehearsals of ‘readiness’ for whatever might come. There is also nostalgia in the pain that accompanies the journey, as the artist described on his Instagram: “Getting caught up in the reordering of perceptions amid frequent repetitions, failures and triumphs builds character. One endures, whatever it takes. However, one never gets quite there. There is history in the way. You look back, indulgent of the past, to a time when things were a bit more settled.”

Serge has never gone back to Rwanda, though he says he would like to. He mentioned he often thinks about his work as a celebration of the endurance of the human body and the human mind. His art speaks about a series of experiences, some very private, which most of the audience will never decipher because it is posed as a riddle that can’t be solved. The point being that, to build that “audience relatability” Nitegeka speaks about, it is not necessary for the people engaging with his work to know about the exact intention or experience behind it, but rather to have an openness to the various social and emotional associations objects might carry. For some, a tent may relate to joy; for others, it may evoke memories of displacement. The key is if such differing responses can find room beside each other. If an artwork—be it through a piece of plywood or a lit tent—can prompt that, and if it can resist evolving meanings in time, then part of the empty riddle’s work is already done.