I have a problem with ‘Black Panther’

Anyone committed to an expansive concept of Pan-African liberation must regard 'Black Panther' as a counterrevolutionary film.

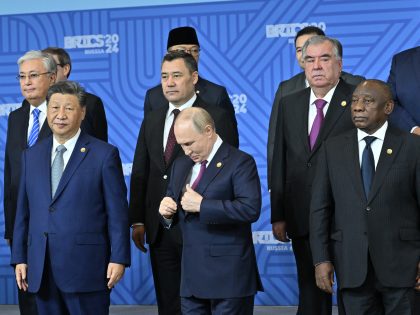

Still from Black Panther.

Black Panther has become a cultural phenomenon unparalleled by any other in recent memory. Rapturous audiences have all but deified the blockbuster film, a remake of a comic book tale about a superhero from the mythical African nation of Wakanda. Viewing the movie has proven especially cathartic for those sweltering under America’s racial politics. With white nationalists on the march and government agencies seemingly conspiring to exacerbate the suffering of people of color, Black Panther’s spectacle of ebony elegance offers more than entertainment; it is a fountain of sweet tea in a searing desert.

Given the dearth of affirming black images in popular media, the impulse to lionize the film is understandable. But Black Panther is more than a celebration of black dignity and sophistication. It is also a discourse on freedom, a dreamscape that draws on black traditions of imagining and seeking to build ideal societies beyond the reach of white supremacy.

Black Panther demands critical examination because utopian visions are unavoidably political; they are among the tools with which oppressed people attempt to draft a just future. Unfortunately, anyone committed to an expansive concept of Pan-African liberation — one designed to free African and African-descended people throughout the world — must regard Black Panther as a counterrevolutionary picture.

That claim may seem unfair, even blasphemous, to fans of the film. After all, Black Panther features a cast of regal and complex black characters. (In a society obsessed with light complexion, it is worth noting that the movie supplies a sumptuous parade of gleaming, mahogany skin.)

Wakanda, moreover, is a model of black self-determination. Blessed with an inexhaustible supply of a wonder mineral known as vibranium, the nation has thrived for generations, escaping colonization and other corrupt influences while shielded beneath a magic dome that conceals the kingdom from the outside world.

Wakanda is technologically advanced and populated by proud and loyal citizens, including a regiment of formidable women warriors.

The problem, from a progressive standpoint, lies in Wakanda’s conservative nationalism. Rulers of the state reject suggestions that they use their technological might to empower other black people across the African continent and around the world. Wakandan leaders maintain a stubborn isolationism, dispatching secret agents on occasional, benevolent missions in foreign lands but eschewing any meaningful program of international solidarity.

This is a stunningly narrow policy. For in the movie, as in real life, those black people not fortunate enough to possess a fantastical energy source endure centuries of slavery, colonialism, imperialism, and subjugation. They are systematically underdeveloped and brutalized, even as their labor enriches their oppressors. Yet through it all the Wakandans remain detached, surrounded by luxury and comfort in what amounts to an enormous gated community. In other words, they behave like any other modern capitalist elite.

In the film, the character most resentful of Wakanda’s insularity is Killmonger, the African-American son of a slain Wakandan expatriate. Raised in a tough Oakland, California, neighborhood, Killmonger is a dark soul, a troubled child of the diaspora who vows to return to the land of his forebears, seize power, and distribute Wakanda’s unrivaled military weapons to oppressed black people across the globe.

In short, Killmonger is a revolutionary. The fact that he is presented as a sociopath is one of the most problematic aspects of the film.

On a superficial level, Killmonger serves as foil to Black Panther’s titular protagonist. As a political device, however, he plays a much larger role, for his character exists to discredit radical internationalism. In fact, Killmonger is the mechanism through which Black Panther reproduces a host of disturbing tropes.

Trope number one: African and African American estrangement

Killmonger embodies the old adage “you can’t go home again.” His quest to “return” to the soil of his ancestors (a place he has never been) is portrayed as tragic and unattainable. Yet there is a great deal of history behind that emigrationist impulse.

For centuries, African Americans and other members of the African Diaspora have sought “repatriation” to the Mother Continent. This yearning for reunification and restoration of kinship bonds is a byproduct of the historical experience of dispersal. Dispossessed and exploited throughout the globe, generations of black folk have craved a land base where they might find security, prosperity, and power. Often they have looked to Africa for such a foundation.

After World War Two, however, the US Cold War establishment sought to disavow any form of grassroots black internationalism. Pundits argued that “the Negro” was exclusively American, that African Americans and Africans were strangers, and that Pan Africanism was a futile and dangerous fantasy.

But Black Americans never abandoned the effort to reclaim African ties. The objective inspired largely symbolic activities in the 1960s and 70s, including the embrace of African cultural garb, hairstyles, and names. Yet it also helped revive a revolutionary consciousness, a belief that the process of decolonization could uproot western imperialism and liberate not only Africans, but African Americans and other subjugated people.

This was not just a black ideal. It was the animating principle of the Nonaligned Movement, a struggle for Third World autonomy and power endorsed by the “Afro-Asian” conference at Bandung, Indonesia, in 1955. The spiritual heirs of Bandung, including Malcolm X, rejected the United States’s self-proclaimed status as “leader of the free world.” They viewed the US as a violent empire and they insisted that “the darker nations” must acquire the power—military and otherwise—to resist American aggression.

Killmonger, it seems, is a fictional grandson of Bandung, though he has clearly failed to digest the movement’s emphasis on peace and human rights as alternatives to expansionism. However, the real American power structure still fears any global alliance that might present an ideological counterforce to US hegemony. So Killmonger is depicted as deranged and his plot to arm those Frantz Fanon called “the wretched of the earth” is cast as a bitter crusade for vengeance rather than as a rational response to the horrors of white supremacy and imperialism.

In this manner, defenders of empire are able to distort the historical project of the Third World left while equating with terrorism any vision of globalization not managed by US capitalism and its allies.

Trope number two: African American pathology

Portraying Killmonger as demented does not merely smear radicalism. It also recycles racist themes of black corruption and immorality. Ironically, this aspect of Black Panther has been largely ignored amid delight over the film’s more auspicious representations of blackness. In truth, though, the flattering depictions are uneven. Black Panther sets African virtue against African-American vice.

The juxtaposition is pernicious. For assertions of black degeneracy often accompany narratives of cultural decline, including the idea that the traumas of slavery or urban life permanently damaged African Americans. As the historian Daryl Scott has shown, such myths have long generated contempt and pity for black America. What they have never done is honor the resilience that enabled black folk to survive the nightmares of the New World.

Cloistered and provincial, Wakanda lacks a revolutionary heritage that might help shape its social institutions or foreign relations. Oakland, on the other hand, possesses a legacy of radical struggle enriched by the irrepressible spirit of African Americans.

Trope number three: the White Savior

If Black Panther rehashes ugly images of African Americans, it also reaffirms the white savior type. In an especially grotesque twist (spoiler alert), the role is filled by a CIA operative who is brought to Wakanda for medical treatment but winds up helping the kingdom defeat Killmonger. The ironies here are legion. One strains to identify a greater foe of the African masses than the CIA, the agency that helped assassinate or subvert some of the continent’s brightest lights, from the Congo’s Patrice Lumumba to South Africa’s Nelson Mandela.

Framing America as a guardian of African interests camouflages the conglomeration of western forces, from global banks to multinational corporations, that have continued to leech Africa’s wealth long after the formal end of colonialism. It also masks the stunning extent to which US militarism has penetrated the continent on behalf of a ceaseless “War on Terror.”

If the Wakandans had read the Martinican theorist Aimé Césaire, they might recognize American imperialism as “the only domination from which one never recovers.” Instead the closing scenes of Black Panther suggest that further collaboration between the kingdom and the global superpower lies ahead.

Black Panther contains other vexing elements. It is curious, for example, that a society as advanced as Wakanda has not renounced monarchical government. (Perhaps creators of the movie share Afrocentrism’s romantic preoccupation with potentates.)

However, the disavowal of radical internationalism may be the film’s greatest sin. For by caricaturing the philosophy, Black Panther repudiates the global consciousness that remains essential to combatting war, domination, and exploitation in Africa, America, and beyond.

Solidarity does not mean unanimity. Stereotype and suspicion continue to color many African encounters with the Diaspora. Yet mutuality based on shared principles can trump both alienation and the condescending uplift mentality that drives Wakanda, by the end of the film, to propose the installation of an outreach center in Oakland.

Black Panther has captured our attention. But it cannot constrain our imagination. We must transcend the film’s conceptual boundaries, restoring a politics that valorizes all black life while demanding the salvation of oppressed people everywhere.