The uncompromising Zoë Wicomb

Zoë Wicomb's fellow South African, JM Coetzee once wrote: "For years we have been waiting to see what the literature of post-apartheid South Africa will look like. Now Zoe Wicomb delivers the goods."

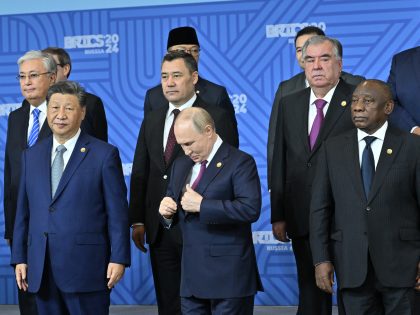

Zoe Wicomb, middle. Her husband, Roger Palmer is on the left. March 2017, Cape Town. Image credit: Sean Jacobs.

Zoe Wicomb is unquestionably among the most significant and widely-read literary interpreters of South Africa. Reading her work from a genderscript is fascinating. My colleague, Meg Samuelson, from the English department, wrote the following on Wicomb’s outstanding contribution:

She’s one of the most consummate literary craftspersons in the world of South African fiction, and among the most acclaimed literary interpreters of South Africa to the world. In the Humanities, we claim that foremost among the social goods we foster are critical thinking and democratic values. I’ve found Wicomb’s fiction and essays to be pre-eminently helpful in advancing this work. They relentlessly strip away structures of authority and scrutinize the commonsensical in ways productive of active, questioning readers and citizens.

Samuelson continued that Wicomb’s brings:

… the Western Cape into a world literary frame – engaging in an uncompromising yet intimate interrogation of its local textures and histories while entangling it in wider worlds.

Wicomb is increasingly receiving international recognition, and deserves to be honoured in her home country – and home region – not least because of her sustained yet nuanced challenges to nationalism, Western Cape exceptionalism and the politics of home.

Among writers, she has asked some of the more probing questions of the post-apartheid dispensation – including: what kind of force does nationalism become when it is detached from national liberation, while still claiming legitimacy from that struggle? What kind of democracy is achieved out of militarized struggle – and masculinist memory? How will the legacies of company, colonial and apartheid rule and their refusals mutate into new social pathologies or potentialities? What does it mean to be at home in a nation and region in which home-place has been denied to so many or is constructed out of racial and gendered terror?

… Black womanhood is the political subject position from which she writes. Yet, while her fictional and critical oeuvre pricks holes in the pretensions of patriarchy and intervenes in structures of racialization, it simultaneously refuses to retreat into identity politics, resisting in turn the complacencies or violence such politics can spawn.

Outside South Africa, Wicomb has been described as “an extraordinary writer” who “mined pure gold from that place [South Africa].” Toni Morrison, the Nobel Laureate and Pulitzer Prize Winner, described Wicomb’s first novel, You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town (1987), as “… seductive, brilliant, and precious, her talent glitters.

Here’s J.M. Coetzee, her fellow South African and a Nobel Laureate as well as twice Man Booker Prize Winner, on Wicomb’s second novel, David’s Story (2000):

For years we have been waiting to see what the literature of post-apartheid South Africa will look like. Now Zoe Wicomb delivers the goods. Witty in tone, sophisticated in technique, eclectic in language, beholden to no one in its politics, David’s Story is a tremendous achievement and a huge step in the remaking of the South Africa novel.

The postcolonial and feminist literary scholar, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, wrote on David Story: “A delicate, powerful novel, guided by the paradoxes of witnessing, the certainties of national liberation and the uncertainties of ground-level hybrid identity, the mysteries of sexual exchange, the austerity of political fiction.”

Her fiction has been nominated and shortlisted for or awarded the following prizes: shortlisted for the Barry Ronge Fiction Prize (for October) in 2015, nominated for the Neustadt International Prize of Literature (for her oeuvre) in 2012, shortlisted for the Commonwealth Prize (for The One that Got Away) in 2009, and was winner of the M-Net Prize (for David’s Story) in 2001.

In 2013, she was awarded the Windham Campbell Literature Prize for Fiction. Wicomb was an inaugural winner of this prestigious new global writer’s prize – housed at Yale University – for an oeuvre rather than single work (Windham Campbell claims to now be one of the largest literary prizes in the world). The prize citation noted that: “Zoe Wicomb’s subtle, lively language and beautifully crafted narratives explore the complex entanglements of home, and the continuing challenges of being in the world.”

Wicomb has had the unusual distinction for a living South African writer of her fiction being the sole focus of three international conferences, each of 2 to 3 days in duration and hosted, respectively, by the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London; the University of Stellenbosch; and, York University. Special issues devoted to her work have been published in the Journal of Southern African Studies; Safundi (double issue); and Current Writing. Her fiction is widely taught – both in South Africa and internationally – and is the subject of numerous completed and in-progress theses, articles and book chapters (reading through the citation lists of her fiction is practically like reviewing the Whose Who of South African literary scholarship).

There are more than one hundred critical studies that engage with each of her first two works, You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town and David’s Story. Currently in preparation are an edited collection of her essays and a collection of articles on her fiction.

Besides her fiction, she is also the author of a number of incisive critical articles on South African and southern African literature and art, including the highly influential essays “Shame and Identity: The Case of the Coloured in South Africa” (1998), “To Hear the Variety of Discourses” (1990; rpt. 1996), and “Five Afrikaner Texts and the Rehabilitation of Whiteness” (1998).

Wicomb is sought after as a reader and speaker at international literary events, and has held a number of fellowships and writer residencies, including at the University of Cape Town, the University of Macau and at the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study. She was the 2015 Chair of Judges of the Caine Prize for African Fiction (the most prestigious and influential Africa-wide literary prize), and has been selected by Nobel Laureate JM Coetzee as one of two South African writers to participate in the “Literatures of the South” program launched at the Universitad San Martin in Buenos Aires in 2016. Currently Emeritus Professor at the University of Strathclyde (where she was previously a professor of postcolonial literature and creative writing), she has been Professor Extraordinaire at the University of Stellenbosch (2005-2011) and was awarded an Honorary Doctorate by Open University (UK) in 2009.

Her mind is like a steel trap. Born in Namaqualand her books reveal a directness. persoon sonder fieterjasies [someone without airs-Ed.], as they would say over there.

The famous French philosopher Hélène Cixous once wrote in The Laugh of the Medusa: “Men have committed the greatest crime against women. Insidiously, violently, they have led them to hate women, to be their own enemies, to mobilize their immense strength against themselves, to be the executants of their virile needs.”

Substitute men/women for white/black as a matrix for this complex writer. Antjie Krog, the well-known poet and political commentator is “begging to be black,” metaphorically. Wicomb, like Krog, confronts us with “the heart of whiteness.” In this time of upheaval Wicomb’s racial script also begs for attention.

Her extraordinary texts reflect on genderscripts, postcolonialism and racial identity. The “shame and identity” of being the Other in a troubled South Africa is the dynamo for her textual reflections.

- Zoe Wicomb was recently conferred with an honorary doctorate by the University of Cape Town. Meg Samuelson nominated Wicomb and assisted in the collection of the material for this edited version of the oration delivered by Hambidge at the graduation.