Love, race and history in Ghana

Historian Carina Ray on her book that explores the history of interracial intimacy in the Gold Coast and Ghana.

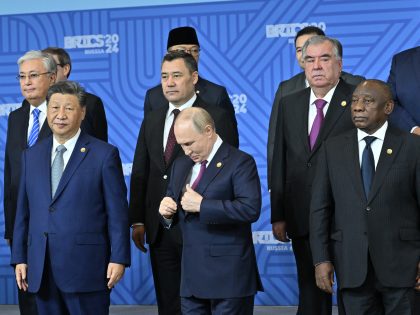

Image from the book's cover.

A couple months ago I was fortunate to read Carina Ray’s excellent new book Crossing The Color Line: Race Sex and the Contested Politics of Colonialism in Ghana on the history on interracial intimacy on the Gold Coast. I decided to interview her and when our conversation moved from political economy and racism to political economy, racism and love, we figured – Valentine’s Day! So here it is: an AIAC take on love, critical politics included.

Why do you think that the history of interracial intimacy in the Gold Coast / Ghana important? What drew you to study it and to these stories in particular?

Let me answer the second question first. When I started the archival work that culminated in Crossing the Color Line, my intention was to write an altogether different book about multiracial people in colonial and post-independence Ghana. Much has been written about them in the context of the precolonial period as cultural, social, political, and linguistic intermediaries—the ubiquitous “middle(wo)men” of the trans-Atlantic trade, especially as it became almost exclusively focused on the slave trade. Hardly anything, however, has been written about this group during the period of formal colonial rule in British West Africa. So I set out to do just that, but quickly discovered that while the archive had much to say about interracial sexual relations in the Gold Coast, there was relative silence about their progeny.

This struck me as an intriguing departure from most early-twentieth century colonial contexts in which anxieties about multiracial people spurred increasing condemnation and regulation of interracial sex. In the introduction and first chapter I spend some time addressing why a book about sex across the color line has comparatively little to say about multiracial people. This was largely because multiracial Gold Coasters during the formal colonial period generally identified themselves, and were identified by Africans and Europeans alike, as Africans. To my mind it would have been ahistorical to write about them as a distinct social group. This allowed me to engage the question of interracial sexual relations in a deep and substantive way in its own right, instead of as a precursor to progeny.

To answer your first question about why this history is important, I have to return again to the nature of my archives. What jumped out at me immediately when I started working with the sources was the extent to which they revealed not only the deeply human and interpersonal dimensions of these relationships, but also the wider grid of Afro-European social relations that they were embedded in. The colonial government’s obsessive focus on interracial sex was methodologically generative because it produced a multidimensional archive that provided surprisingly detailed accounts of the conflicts and connections that characterized the everyday lives of and interactions between Africans and Europeans. What at first glance may seem like a narrow focus on interracial sexual relationships actually opens up an unprecedented view into colonial race relations in the Gold Coast. Part of what makes these relationships so compelling and important, then, is their potential to recalibrate our thinking about colonial economies of racism in ways that allow us to see greater parity between settler and administered colonialism without suggesting an equivalence.

But these relationships are also important in their own right, not least because so many of them force us to reckon with the unsettling gray area where racism and affect could and often did coexist. How else can you explain the British doctor who risked his distinguished career as a colonial medical officer to marry across the color line, and then proceeded to maintain his membership in a Europeans-only club that barred his African wife? In this and in so many other instances where I was confronted with relationships that resisted neat categorization, I found myself recalling Frantz Fanon, who in writing about interracial intimacies in Black Skin, White Masks, says “Today we believe in the possibility of love, and that is the reason why we are endeavoring to trace its imperfections and perversions.” I can’t think of a more profound or precise theoretical approach to the problem of love, in general, and the problem of love across the color line, in particular. This is not to suggest that all of the relationships I document in Crossing the Color Line were loving, but rather to say that loving relationships were not immune to the racism of their time.

Why and how did interracial sex go from being a fact to being a problem?

Although both Africans and Europeans most forcefully articulated interracial sex as a problem during the colonial period, I think its important to point out that during the precolonial period Africans tightly regulated these relationships in ways that indicate that they recognized their potential benefits and risks. Likewise, the various European powers that held sway along the Gold Coast managed their varying anxieties over these relationships in ways that recognized their indispensability to the European presence on the coast. That’s an important background to the question so that readers are not mislead into thinking that the Gold Coast was an interracial sexual utopia prior to the onset of formal British rule.

What was different about the first decade of the twentieth century was that the hyper-racialization of formal colonial rule meant that the very things that had once made interracial sexual relationships indispensable—namely their ability to acculturate and integrate European men into local societies in ways that allowed them to develop beneficial reciprocal networks—were now “undesirable.” Indeed that was the very term Governor John Rodger used to describe relationships between African women and European officers when he officially banned them in 1907. Coming on the heels of “a century-long shift from a Britain that asked to one that demanded and a last commanded,” to borrow from Tom McCaskie, the ban on concubinage not only signaled a new political modus operando, it also heralded a new era of colonial racial insularity, albeit one that was never fully achieved.

Readers won’t be surprised that interracial sexual relationships emerged as a “problem” under formal colonial rule, but what I hope to show is that making concubinage a punishable offense did more to undermine British authority than it did to preserve it. This is particularly evident not only in the individual disciplinary cases brought against offending British officers, but also in the wider current of anticolonial agitation that swelled around the increasingly illicit nature of interracial sexual relations. These relationships could no longer be publicly recognized and so they appeared all the more unseemly to Gold Coasters, who used them to call into question the moral credibility of British colonial rule. In short it was how the British chose to manage concubinage, as a problem, that actually became the bigger problem in the end.

I want to pursue an issue you raised in your first response. What about love? Where is the scholarship on love in African history? We hear a lot about pain, we learn a lot about anger and hate, but what of affection? How do your stories contribute to the history of love and what lessons do they teach us for love’s present?

Your question rightly points to a massive lacuna in our field, but also to deeper more unsettling questions about why historians have, until very recently, neglected love as a historical force and object of analysis in Africa. That pain, hate, and ager, to which I would add fear and suspicion, surface so frequently says more about the biases that shape our field, than it does about the affective and emotive economies that shape the lived experiences of African peoples, past and present. I would be remiss if I didn’t add that in as much as I think Africanist historians need to move beyond functionalist or transactional approaches to sexuality, marriage, and allied concerns, to get at affect, I also think that the scholarship on love elsewhere in the world would do well to remember just how intertwined affect and function can be…just how transactional love can be. Forget about romantic love, anyone with a kid knows that love is amenable to being bought!

But back to the scholarship. When Jennifer Cole and Lynn Thomas published Love in Africa – a book that is never out of my arm’s reach – I remember thinking to myself, this book is as close to a mic drop as any of us Africanist historians will ever come! TADOW! For me their book is the “call,” and now the question is, what’s the “response.” Jennifer had already pointed the way with Sex and Salvation: Imagining the Future in Madagascar, a beautifully and persuasively written historically-informed ethnography, and Rachel Jean-Baptiste’s Conjugal Rights: Marriage, Sexuality, and Urban Life in Colonial Libreville, Gabon takes up the challenge too. I also appreciated Pernille Ipsen’s analysis of love in her book Daughters of the Trade: Atlantic Slavers and Interracial Marriage on the Gold Coast, which moves beyond a purely functional or pragmatic reading of Ga-Danish marriages in the context of the transatlantic slave trade. But clearly much more work is needed on this front.

In the case of Ghana and Britain both colonial racism and anticolonial resistance conditioned the possibilities for love across the color line in the twentieth century. The raced and gendered configuration of couples—African woman/European man or African man/European woman—and the respective political and social geographies of colony and metropole they inhabited shaped not only the kinds of emotional ties that developed, but also our ability as historians to interpret those ties. I was constantly aware of how much more fraught it was to write about the affective ties between African women and European men in the Gold Coast than about about love and affection between African men and European women in the British ports or elsewhere in Europe. Comparatively fewer caveats seemed necessary and I am still grappling with the why of that, especially since Marc Matera does such a superb job of showing just how racially vexed those relationships were in Black London: The Imperial Metropolis and Decolonization in the Twentieth Century.

But I also think there is something more fundamental at work in how people think about love as a panacea that is profoundly reductive and hinders our ability to see the ways in which love has and continues to coexist with racism…and a range of other isms for that matter. It’s clear from many of the stories in Crossing the Color Line that a variety of affective ties grew amidst the racism and exploitative and unequal power relations that shaped these relationships. That observation still holds true. I’m always struck by the lack of attention paid to how racism operates internally within interracial relationships today, yet there is no shortage of reportage, like this and this, emphasizing how external societal racism negatively impacts interracial couples. The assumption seems to be that if you are in an interracial relationship you can’t be racist. Well, we know that’s not true.

You’ve given us a lot to think about. I know that some historians don’t like being asked about what their work means for our present and future, but I was hoping you could underline your book’s contribution to ongoing conversations in the continent and diaspora. What do you hope readers take away from your work?

Actually, I take a very different approach. I think its crucial, especially as Africanists, to think about what our work means for the present and future precisely because the African past is always at play in the ways that people think about, talk about, write about, make policies about, etc., etc., Africa today. The very fact that our field is in itself a repudiation of centuries of racist thought about Africa’s lack of history and its lack of coevalness with the West, points to the urgency of actively engaging the present and the future, when and where possible, in our research.

That ideological commitment is at the heart of my book’s conclusion. In the section on “Interracial Heterosexuality, Homosexuality, and States of Panic,” I draw on the insights gleaned from my work on colonial interracial heterosexual relations in Ghana to think through the recent intensification of church and state-sponsored homophobia in a number of different African countries. Subjecting contemporary homophobic discourses to both comparative and historical analysis reveals them to be part of a much longer history of sexual panics visible across different parts of the continent, especially during the colonial period and continuing through today. In taking this approach, what I hoped to show is that homophobia in places like Nigeria, Zimbabwe, and Uganda today does not represent an incomprehensible form of African social conservatism, a claim that inevitably leads down a slipper slope toward old tropes of African backwardness and stasis, underpinned, as they are, by the idea that Africa and modernity are incompatible. Rather, like the sexual panics that gripped their colonial predecessors, it is better understood as a symptom of deeper anxieties and social dis-ease occasioned by the crises facing the state in post-independence Africa – of which those at the forefront of this disturbing trend are unsurprisingly also those facing particularly acute crises of legitimacy.

What’s next? Where do you go from here?

I have the tremendous privilege this year of being at the Society for the Humanities at Cornell, where I’m getting started on my new book project, tentatively titled “Somatic Blackness: A History of the Body and Race-Making in Ghana.” In so many ways this is the book that I thought I would write first, so it represents a return to the foundational questions about race, identity, blackness, and the body that first captured my attention as an undergraduate study abroad student in Ghana in 1993! Wow, I really just dated myself there.