What is the university for?

We should not be tempted to idealize the university ‘as it was’ – especially in a country like South Africa.

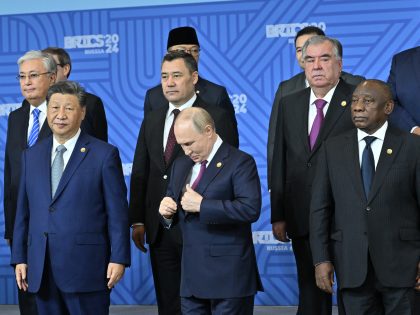

Image Credit: Nicholas Rawhani

In the wake #FeesMustFall protests that electrified South Africa one week ago, much has been made about the way in which universities have been bent to the needs of international capital and its neo-liberal demands. Students and workers rightly condemn the expense, outsourcing and indebtedness that make a mockery of the university’s’ ‘ideals’ of thoughtfulness, critique and freedom. This should be so. Yet we should not be tempted to idealize the university ‘as it was’ – especially in a country like South Africa, where universities have meant oppression, segregation, epistemological violence and apartheid, as much as (or even more than) they have meant ‘knowledge.’

Instead, unlike in the global north, in South Africa the possibility exists to admit to two ways we hear the parsing “for” in “what is the university for.” On the one hand, we hear a question about what the university is supposed to be doing now, and on the other, we hear a question about the university’s standpoint. With the emergence of a new scripting of the university in the image of capital and its drive to accumulation, the question of what the university stands for seems to take precedence over the question of what the university is to be doing now. The demand is not to reverse the orders of these questions but to realize that in South Africa today, the opportunity exists to study both senses of hearing the phrase “what is the university for”, in their very simultaneity, and at whatever speed. In such simultaneity the university may open itself to a future in which it more searchingly requires its students, faculty and workers to think ahead by asking what we should be desiring at the institutional site of the university.

We would be remiss if we did not think of the university as more than an institution that preserves the best of what we have learned for the greater public good. The university is, and must be uncompromisingly intellectual in its desire, commitment and pursuits of these two simple, albeit contested ends. An emphasis on what the university ‘was’ is conservative; we need to be thoughtful. The university is perhaps to be approached less as a question of putting knowledge in the service of the public, than as a space for inventing the unprecedented. .

As much as universities are thought to advance knowledge, its reigning ideas have shifted considerably over the centuries. If at one moment the reigning idea of the university was that of reason, it later emerged as an institution grounded in the concept of culture. Today it is being appropriated to the logic of the market and a prospective future of growing indebtedness. Taken together, this latest installment of the idea of the university that appears to be proliferating globally is creating a deep sense of anxiety, alienation, and a feeling of proletarianization. The university is becoming a hyper-industrialized information machine that is beginning to reveal itself as an information bomb.

In contrast to the hyper-industrialized information machine, the university’s uncompromising intellectual sense historically derives primarily from the idealism that brought it into being, and in the second, in its overwhelming, but not exclusive location in the changed circumstances of the Second World War. Such idealism contended with the hegemonic formations of state, capital and the public sphere in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In Africa, the birth of the university accompanied the wave of nationalist independence movements that swept through the continent in the aftermath of the Second World War, with the promise of development underwriting its public commitments. And in South Africa specifically, the university was tied more fundamentally to the determinations, intensification and demands of a racializing state and capitalist formation. The distortion in the original idealism of the university has been overtaken by the long twentieth-century in which the university became entangled in an even longer process of dehumanization. It has also been overtaken by a rapid expansion of technological objects through which research and teaching are now extensively mediated, resulting in, among other manias, the fetish of outcomes and measured results.

Bound at once to a contract with the state and simultaneously to a public sphere, the university has had to reinvent its object of study, abiding by duration and commitments to the formation of students in respect of its reigning ideas. It is in the interstice of these seemingly opposing social demands that the inventiveness of the university as an institution is most discernable. Rather than being given to the dominant interests of the day, whether state, capital or public, the university ought by virtue of its idealism to be true to its commitment to name the question that defines the present in relation to which it sets to work, especially when that question of the present may not appear obvious to society at large. Yet, in naming this question the university is ethically required to make clear that it does not stand above society.

Today there is growing concern that the university has lost sight of its reigning idea – the demands of radical critique and timeliness – and all the contests that ensue from claims made on that idea. In the process its sense of inventiveness has been threatened by an encroaching sense of the de-schooling of society, instrumental reason and the effects of the changes in the technological resources of society that have altered the span of attention, retentional abilities, memory and recall, and at times, the very desire to think and reason. Scholars around the world bemoan the extent of plagiarism and lack of attention on the part of their students; features that they suggest have much to do with the changes wrought by the growth and expansion of new technological resources. What binds the university as a coherent system is now threatened by the waning of attention and the changes in processes of retention and memory. In these times, retention has been consigned to digital recording devices. Students and faculty are now compelled to labor under the illusion that the more that we store and the more we have stored, the more we presumably know.

Here again we can learn from our past. The movement that unfolded in the 1980s at SA universities was a statement of force against the cynical reason of apartheid, yes, but it also contained an element of the creative act, the process of inventing the unprecedented, which underwrote every effort at turning apartheid’s rationality on its head. It is a version of the creative act that is now threatened by the onset of memory loss. In its place seemingly more vacuous words have come to take the place of formidable concepts in formation. Words such as ‘efficiency’ and ‘excellence’ now replace more thoughtful and thought-provoking notions of “epistemological access”. Where the concept of “epistemological access” generated extensive curricula debate in the 1980s, efficiency and excellence serve as buzzwords with little or no epistemic grounding. And newer scripts of creativity are producing fantasies that may yet prove to be the nightmare for students in the future. The speculative logic of the student as an entrepreneur of the self lends itself to the promise of consumption and fulfillment, but at the same time, drags students into a state of limbo and mere functionality. Against this slide into mindless creativity, an older notion of the creative act, like the notion of a work of art that resists death, must surely be a possible concept upon which to constitute a future university. This is a work of art that calls on a people that does not exist yet. It is the idea of the university that creates the space for the invention of the unprecedented.

There has never been a more hazardous time to forget to ask “what is the university for?” The university’s future resides in cutting into the future and into established knowledge. All the while, we should hear in the echoes of the past, the demand to keep desire alive, to remain awake, and to constitute a community that is open to the future.

In South Africa, where the university under apartheid was placed in the service of a cynical state rationality that divided society along race, class and gender lines, the question of our time now demands that we ask how we reinvent the idea of the university. We need to think once again about approaches to technology, the state and the public sphere – and how each gives a view on the desire that now remains repressed in our respective knowledge projects. We need to recuperate the sense of attention and play, of the creative act as opposed to the banality of neoliberal creativity, that will prove indispensable for naming our present and finding our way out of those predicaments that threaten to undermine the best of our knowledge upon which the future of our students, faculty, its workers and that of the institution of the university rests.