African Radio’s growing and enduring popularity

Growing numbers of radio stations, across the continent, are training young people to deliver news to their peers themselves.

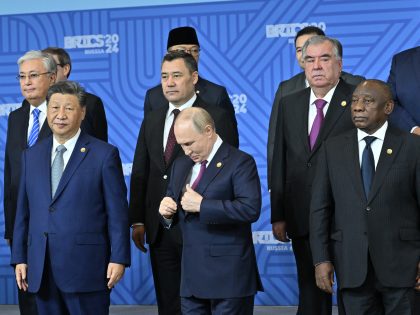

Image: Bush Radio.

A few days ago, I overheard a BBC World Service presenter announce during an on-air discussion on media in Africa by saying that many young people “do away with radio and television” and get their news online and from each other instead.

But do they really? Have new media, such as internet, SMS, smart phones and social media platforms taken over radio’s role as news provider? With all those technologically savvy young people, browsing, downloading and discovering the online world in internet cafes, did radio indeed lose its relevance to young people in Africa?

Now, the meanings of both ‘Africa’ and ‘young’ vary, but if we take Africa in its Sub-Saharan shape and ‘young’ as a life stage somewhere between 15 and 30 (although it really depends on who you ask) the answer that emerges from some simple stats looks like a no.

Even with the improvements in internet access, only a small share of youth in Africa actually enjoys the privilege of steady and reliable connectivity. Access to broadband differs per country, but the realities of Africa’s current online capacity still restrict the majority of young people from fully entering the online world of 3G. And those who do have access to (reliable) 3G are usually the richer urban youth. Levi Obijiofor has written a great chapter on this topic in Herman Wasserman’s book Popular Media, Democracy and Development.

If we are to believe UNESCO, the proliferation of radio in Africa — a process which started when many of the airwaves opened up about 20 years ago — is alive and well today. Following some radio research carried out by Mary Myers, the medium’s growing and enduring popularity as a means of accessing news, information, entertainment and music seems all but fading.

No surprise, really, if you think about some of radio’s advantages. Readily available, immediate, pervasive and affordable, radio is the only reliable means for information and knowledge exchange in many communities where access to electricity, internet, telephones and television is not all that common. And unlike most other news outlets, especially online ones, radio does not discriminate against those who cannot read and write.

Of course, radio’s power and reach can and have of course been (mis)used to spread divisions and hate as well, but its high accessibility still renders it one of the most democratic forms of media. This accessibility can mean a lot of different things for different people. For those who look for ‘informed citizenship’, it might be most important to stay up to date about national or local political developments, when others might be more interested in radio’s ability to offer a window into the world beyond the boundaries of their own communities or countries.

Radios are also light, portable and affordable, which makes them easy to pick up and move around. And by being pretty straightforward to learn, radio is a great platform for young people to produce and create news as well, rather than simply consume it. At a time when ‘youth empowerment’ and ‘youth participation’ continue to buzz around political and development circles, radio might better be conceived as a medium of opportunity for young people in Africa, rather than something they are massively doing away with. The growing interest in youth-centered and youth-led radio shows in Africa attest to the medium’s continuing popularity.

Today, growing numbers of radio stations, across the continent, are training young people to deliver news to their peers themselves.

The fact that today, as a news medium, radio seems to trump online media in accessibility and therefore popularity doesn’t mean that the information revolution isn’t happening, though. It is, and it takes many different and exciting forms. But the improvements in ICTs and infrastructure in some areas don’t mean young people are ‘doing away with radio’ all over the continent. It’s not an either/or story: ‘old’ and ‘new’ media can converge as well; radio shows can be shared on the internet, videos can be played and shared with smart phones (by those who do have access to it) and listeners can use their mobile phones to participate in live TV or radio shows.

So yes, let us celebrate new media and online news, but also keep in mind that revolutions tend to be slower than we’d sometimes like. It will take a while before the majority of young people in Africa will reap the new media fruits. Meanwhile, let’s also give it up for radio.