The Unruly Rush of the City

Julie Mehretu's canvases depict a public zone dichotomous to that of their own surrounding, brimming with a sense of the life of a city which we can never really know or measure, whose politics is alive but oddly incubated.

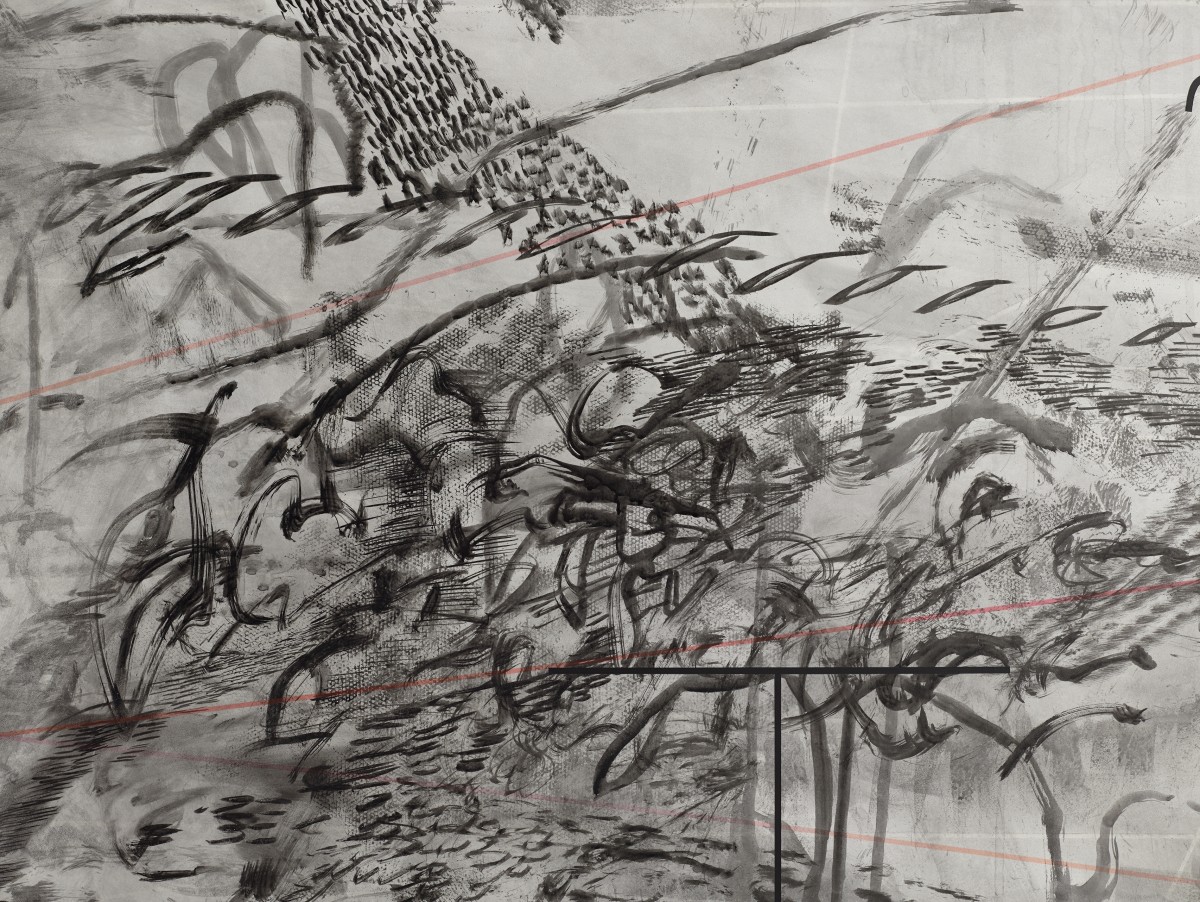

"Invisible Sun" by Julie Mehretu.

It is as if Julie Mehretu has boxed some corner of a great, rambling city, shaken it, and spilled the contents out onto a canvas. Girders and struts, and the faint memory of the structure and reason that once guided their making, lies broken. Now, on the canvas, these once straight lines are contaminated with the inevitable growths and architectural warts that bloom as cities age – the shacks, kiosks, burnt out cars, potholes; the mess of city life.

In these huge, monument-sized canvases that hang in White Cube Bermondsey, Mehretu’s work addresses the unreason of the city, its visual noise, and in her deft fusion of geometric drawings and the endless abstractions she paints and draws upon them, they sprawl like the cities themselves, descending into a kind of visual madness that reflects the peculiar, frenetic condition of urban life.

In Kabul (2013), delicate, architectural pencil drawings seemingly self-multiply, over and over. Mehretu overwhelms their rationale – the faint, straight lines re-accumulate so many times that the buildings they once depicted drown beneath, only discernible from a corner here and there, or a window that survived the brambling swarm of Mehretu’s markmaking that grew out of its foundations, like some parasitic shrub.

Beside it hangs Invisible Sun (algorithm 2) (2013), a cloud of grey and black acrylic. Perhaps if Henri Michaux, long into a Mescaline binge, had tried to paint a city, it would have looked something like this. The painting rushes with movement; wide smeared brush strokes shroud the canvas in a thick fog. It brings to mind the atmosphere of cities not yet cleaned and filtered by European pollution laws; like a walk through downtown Nairobi that results in black snot and dust in every crevice, while exhaust pipes cough plumes of black smoke, hungry for cheap petrol.

Mehretu captures the unruly rush of city life in a terribly convincing way, and visually mimics something of its anti-logic. And yet, there is a paradox that troubles her work.

At White Cube, the architect David Adjaye has designed an altar-like chamber composed of four walls, dramatically lit, angled and facing towards one another. Here hangs the Mogamma: A Painting in Four Parts, which was first shown at dOCUMENTA 13. The complexity and detail of the quadtych is immense. The title refers to Al-Mogamma, the name of the all-purpose government building in Tahrir Square, around which swarmed the protests of 2011, which eventually ousted Hosni Mubarak. In these four paintings, Mehretu has taken plans and drawings of countless city squares and layered and abstracted them beyond recognition. Once again, her deft markmaking transforms layer upon layer into a thriving mass – flashes of neon might be traffic lights, lines and arrows could be the campaign map of an oncoming army, or it could almost be a photograph of a post-apocalyptic terrain, perhaps from Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. But their home, in this cathedral-like gallery space, contradicts the public histories they summon.

These are large, monumental pieces; a collectors dream, a princely addition to any private collection. As Karen Rosenberg in the New York Times pointed out, ‘In 2007 Goldman Sachs commissioned an 80-foot mural from Ms. Mehretu for the lobby of its new building in Battery Park City’. Mehretu has been embraced by the financial sector, yet the spaces of revolution she depicts – and which form the bulk of her recent work – seem to demand a messier, less precious home.

There is an uncomfortable juncture between the expensive curation and the exciting and vivid urban sprawl that her paintings and drawings explore. And a tension, too, in the co-option of her work by large banks and institutions, whose recent apocalypse she does not directly address, yet which hovers here, like an uncomfortable specter, for they surely have had a huge impact on the ‘formation of personal and communal identity’, so central to her artistic interest. Instead, the exhibition skirts these more challenging questions. The canvases depict a public zone dichotomous to that of their own surrounding, brimming with a sense of the life of a city which we can never really know or measure, whose politics is alive but oddly incubated, but which exists here in some compelling form, in Mehretu’s scrum of marks and gestures.