The films of Sarah Maldoror

Maldoror on filmmaking: "To make a film means to take a position ... I make films so that people—no matter what race or color they are—can understand them."

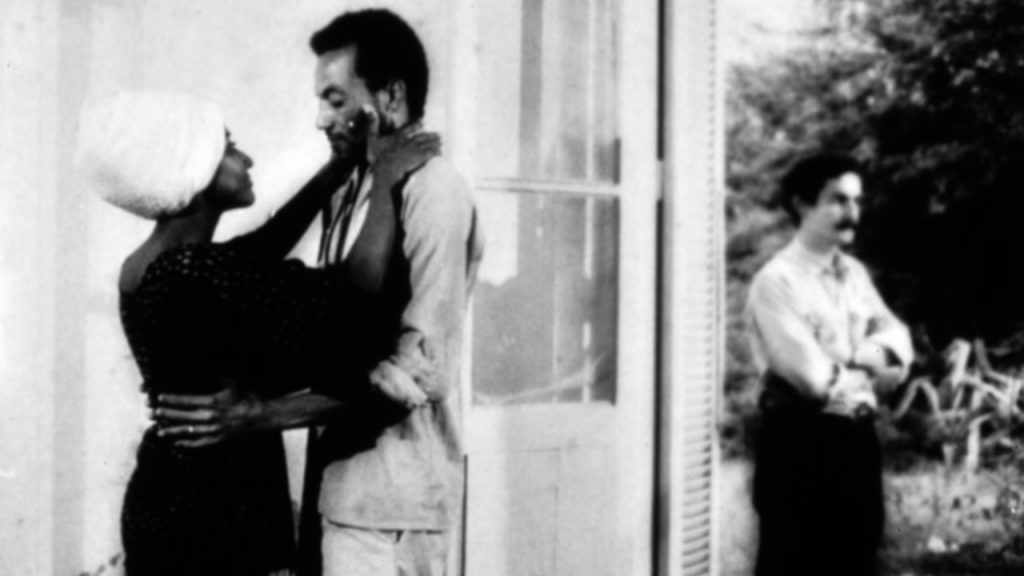

Still from Sambizanga by Sarah Maldoror.

Sarah Maldoror’s film Sambizanga (1972) is a courageous and powerful piece of filmmaking. Beautifully shot in 35mm film, the director masterfully tells the story of a young couple—Maria and Domingos—who enjoy a seemingly blissful family life with their young baby, until Domingos is seized by the Portuguese authorities for being a suspected political activist, and taken to a brutal prison in the city. The film follows Maria on her heroic journey to find and save her husband; the narrative is punctuated by her heartbreaking cries; “Domingos!” and her encounters with officials who turn her away, while Maldoror cuts to scenes of her husbands torture, creating a sense of frantic urgency to the film.

Sambizanga captures a moment in Angolan history where a tide turned. By deliberately setting the film in the past—11 years previously—Maldoror is able to show the deaths and acts of brutality that served to both unify and advance the liberation movement. She shows, as she says in her own words “the political consciousness of the people had not yet matured.” Domingos’ torture and Maria’s struggle to learn the truth are symbolic of a generation of people becoming politically aware. At a time when a single death was still an inconceivable act of violent oppression, Maldoror’s narrative captures a society on the knifepoint of change. Later in this period, death and injury were common in the fight for freedom; it is estimated that by the end of 1961, the first year of the war, 50,000 Africans died as a result of rioting, massacres, mass executions and torture, while approximately 450,000 fled to neighboring Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo).

Maldoror is honest about the didacticism of her film; “to make a film means to take a position, and when I take a position, I am educating people. The audience has a need to know that there’s a war going on in Angola … I make films so that people—no matter what race or color they are—can understand them.”

Her approach to her art has consistently been one tied up in the world of politics, and in the desire for political change. Her personal life is an astounding story in itself. Maldoror is of Guadeloupian origin, but moved to Paris early in her childhood. She was invited in her youth to study film at the Moscow Film Academy in the early 1960s, under the eye of the great Russian director Mark Donskoi. Here, following in the footsteps of the “godfather” of African Cinema, Ousmane Sémbene, she learned about politically committed cinema, developing a revolutionary aesthetic of her own. She worked as an assistant on Gillo Pontecorvo’s celebrated film The Battle of Algiers (1966), and soon after made her first short film “Monamgambée” (1969), which acts as both a narrative and technical practice for her later feature Sambizanga.

Maldoror was by no means an outsider to the liberation movement in Angola. She was closely involved with the MPLA—the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola—as her husband, Mario de Andrade was its former president, who had a close role in the writing of Sambizanga’s script. In her life, as in her films, Maldoror is concerned with community, action and politics. Her scripting of a powerful, stubborn and loving woman as the central character of her feature film both embodies and provokes the complex notions of community during struggle, and what political struggle really is. Domingos is “the activist,” brutally treated for the possession of a mere flyer, his struggle is physical, degrading, the scenes of his torture are difficult to watch for Maldoror has so adeptly shown us his compassionate and loving character in an earlier family scene at his home. Maria’s struggle is protracted, anguished, in the dark. A community of women come to her aid to remind her of her responsibilities to her child. Maldoror achingly reminds us of the ongoing struggle to continue living in such politically volatile times.

The narrative trajectories that Maldoror shows us skillfully unravel a political situation made up of individuals. In the final scene of the film, we see the activists dancing, socializing; upon the news of Domingos’ death, they stand in a circle and celebrate—it is both a moment of mourning and of joy, for as Mussunda—one of the leaders—says, Domingos has begun his real life, at the heart of the Angolan people. This line captures the true spirit of Sambizanga; its will to show the development of a strong political consciousness and a will for change in Angola.