Firearms aren’t the only weapons

The writings of revolutionary Angolan leader and intellectual Mário Pinto de Andrade helped galvanize the independence struggle. They are now available in English.

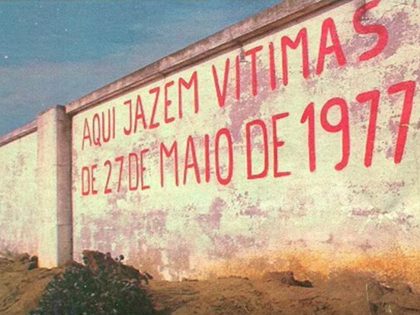

Photo by Olhar Angolano on Unsplash.

Music, rhyme, poetry, and art in general have the power to invade us, to overflow from within, to redirect our course and orientation, transforming our reality through sensibility and energy. Words possess power, they belong to us, and we can share them. Material goods such as clothes, houses, cars, and phones can vanish, but the power of our words and ideas remains for life and beyond, marking generations and nurturing ancestry.

This impact reverberates in the recently released book The Revolution Will Be a Poetic Act: African Culture and Decolonization, a selection of texts by Angolan thinker Mário Pinto de Andrade (1928–1990). The title of the book evokes the iconic song “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” by Gil Scott-Heron (1949–2011). With his questioning, ironic, and political style, Scott-Heron became a key figure of the golden age of Black music and a pivotal influence on rap. Like the song, the book’s title underscores the cultural layer of revolutions, which neither were nor will be televised. Revolutions are not simple events that can be easily accepted or broadcast by mainstream media; they involve multiple disruptive and complex layers in dispute. As Scott-Heron stated in his song, the revolution will not be televised “in four parts without commercial interruptions.”

The Revolution Will Be a Poetic Act was published at the end of 2024 by Polity Press. The book was edited and translated by Lanie Millar, associate professor of Spanish and Portuguese, and Fabienne Moore, associate professor of French, both at the University of Oregon. Combining their expertise in decolonial African literatures, they brought this work to life. The volume gathers essays, speeches, and reflections by the Angolan intellectual, poet, and political figure Mário Pinto de Andrade—an important name in the African and global anticolonial movement. The publication represents an effort to make Andrade’s poetic-political thought accessible to English-speaking audiences, linking his intellectual contributions to the broader struggle for decolonization.

Born in Golungo Alto, Angola, Andrade studied in Luanda before pursuing higher education in classical philology at the University of Lisbon, where he encountered the racial and political tensions of colonial Europe. Brazilian historian Helena Wakim Moreno has explored how these experiences led Andrade to shift his academic focus toward African linguistics and cultures, culminating in studies on Kimbundu, a language of the Ambundu ethnolinguistic group. His essay on Kimbundu, published in Luanda, served as an anticolonial critique of grammars and dictionaries produced since the 17th century.

Andrade was one of the founders of the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) in 1956 and became its first president in 1960. Even in exile, he continued to shape African political-cultural thought through publications and reflections on nationalism and decolonization. His influence extended beyond Angola, notably between 1965 and 1969 through the Conference of Nationalist Organizations of the Portuguese Colonies (CONCP), a key coordinating space for liberation movements across Africa during the armed struggle.

His personal archives—letters, manuscripts, and various documents—are accessible through the Fundação Mário Soares website and offer valuable resources to researchers interested in Angola’s anti-colonial history, complementing the material presented in the book.

The volume is divided into fifteen parts addressing key topics to understand the interplay between culture, race, identity, and anticolonial struggle. Highlights include reflections on Black poetry in Portuguese (“Black Poetry Expressed in Portuguese”; “Black Poets of Portuguese Expression”), critiques of Lusotropicalism and assimilation ideology (“What Is Lusotropicalism?”; “Black African Culture and Assimilation”), and analyses of culture’s strategic role in armed struggle (“Culture and Armed Struggle”; “The Armed Song of the Angolan People”; “Culture and National Liberation in Africa”). The collection also includes more theoretical texts, such as “Theoretical Production of African Intellectuals,” and two interviews that illuminate Andrade’s personal and familial trajectory.

In the sections focused on culture and poetry, Andrade’s writings highlight how Black African intellectuals creatively appropriated the Portuguese language as a symbolic form of resistance to colonialism. By challenging assimilationist dynamics and the myth of Lusotropicalism, he exposed the cultural domination enforced by the Portuguese regime and the false promise of social inclusion through acculturation. His texts, such as “The Armed Song of the Angolan People,” emphasize how songs, poems, and oral narratives served as political instruments on the front lines of struggle.

By revisiting Mário Pinto de Andrade’s thought, this book bridges the anticolonial past with present urgencies. Its ideas transcend oceans and echo, especially within Global South academic centers. Historically, universities such as Dakar, Ibadan, and Dar es Salaam played a key role in shaping intellectuals committed to emancipatory and pan-Africanist projects. In Brazil, these debates have become foundational in African and Afro-diasporic studies, with notable contributions from institutions such as the Center for Afro-Oriental Studies at the Federal University of Bahia, the Center for African Studies at the University of São Paulo, and the now-defunct Center for Afro-Asian Studies at Universidade Candido Mendes.

In addition to recommending the book, we also suggest the article “The Films of Sarah Maldoror” published by Africa Is a Country, to learn more about Andrade’s wife, Sarah Maldoror, one of the pioneering filmmakers of African cinema. Reading Mário Pinto de Andrade today means recognizing the continuity of an intellectual and activist tradition that links Africa and its diaspora, memory and action, word and revolution. This collection is not just a tribute, it is a call to anti-Eurocentric studies.