Algeria and the Black Panthers

In the 1970s, Algiers served as refuge to African Americans who confronted US racism with force and had to flee the country. Some Panthers hijacked planes.

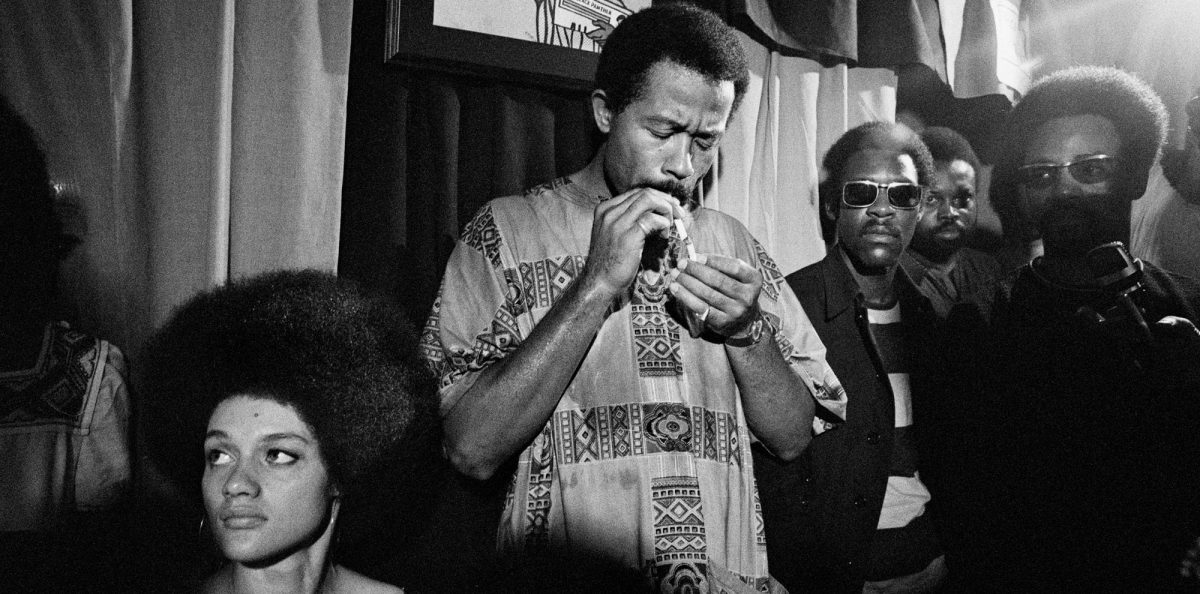

Eldridge Cleaver and wife Kathleen Cleaver, Algiers 1969. Image: Bruno Barbey/Magnum.

As airline travel became more common in the 1950s and 1960s, hijacking planes also became a common practice. By the early 1970s, nearly 160 high jacking incidents occurred.

The book “The Skies Belong to Us” by the American writer, Brendan Koerner, charts some of this history of the golden age of airplane highjacking and connects it to the activities of the Black Panther Party and the party’s international office in Algiers.

Koerner’s account of skyjackings in the US in the 1960s and 1970s is nothing short of surreal. In that unimaginable world, passengers did not undergo TSA screenings, there were no scanners, did not even have to show boarding passes or IDs, and sometimes even paid for their tickets after reaching their destination. Skyjacking was not even illegal in the 50s and high-jacking airplanes had very little to do with political cause. One of Koerner’s most entertaining examples, a man who diverted a plane to Cuba because he was missing his mom’s style frijoles.

To think that there was a time when riding an airplane in the US was almost as easy as getting on a bus is almost as phantasmic as thinking about Algiers as once the refuge to African Americans who confronted US racism with force and had to flee.

Algeria was one of the favorite destinations for hijackers, beside Cuba.

Newly independent Algeria had a deep flair for revolutionaries. Houari Boumédiène, Algeria’s second president and revolutionary leader, showed unconditional support of the Palestinian cause and Western Sahara, had close ties with Nelson Mandela (and the South African liberation movement), Yasser Arafat and the PLO, Fidel Castro and the Cuban revolution, and authorized actions such as welcoming the international section of the Black Panther Party and the Canary Islands Independence Movement (MPAIAC) – which aired their radio station from Algiers. Boumédiène’s solidarity with revolutionary movements across the globe earned the country a reputation of being a revolutionary heaven, a Mecca of sorts of revolutions.

One side effect was that Boumédiène’s internationalism also turned Algiers into a popular destination for politically-motivated highjacked airplanes. In fact, in 1975 Venezuela’s Ilich Ramirez Sanchez and his 42 hostages landed in Algiers putting Abdelaziz Bouteflika (then-minister of foreign affairs; now the President) in the negotiator’s seat. In 1977 leftist Japanese Red Army guerrillas landed their high-jacked plane and surrendered in Algiers, and in 1970 when 40 “Brazilian political prisoners were exchanged for the kidnapped West German Ambassador,” they requested to land in Algiers where they were welcomed with cigarettes.

But perhaps one of the most dramatic stories of planes highjacked to Algiers had to be the two airplanes highjacked by Black Panther members Roger Holder and George Wright and commandeered to Algiers in 1972. By then the Black Panther Party had opened an international chapter in Algiers led by Eldridge Cleaver who decided to seek exile in Algeria once Cuba did not look safe enough. Eldridge was in the company of several Black Panther Party members who were very active from the Panther offices in Algiers. Indeed, Donald Cox, Pete O’Neal, and Kathleen Cleaver were based there, and it made sense for Holder to set Algiers as the destination of his highjacked plane.

On June 2 1972, Western Airlines Flight 701 with 98 passengers and a seven-member crew was hijacked in Los Angeles by Holder and Catherine Marie Kerkew. The flight was on its way to Seattle when Holder executed his long-planned “Operation Sisyphus.”

Holder was a US army veteran, toured Vietnam four times, but on his third tour of Vietnam got arrested for possessing marijuana in Saigon. His time in jail made him not only experience firsthand race oppression of African Americans within the U.S. military, but also made him deeply reflect on the war effort and the injustices he experienced both as a perpetrator and a victim of the war machine. Holder’s traumatic memories of his friends killed in action and his disillusionment with the Vietnam War haunted him for the rest of his life. He planned the skyjacking as a way to get out of the feeling of guilt he felt for both participating in the war and surviving it. He also wanted to put pressure on authorities to free Angela Davis who was then standing trial for murder.

Kerkew was Holder’s companion, accomplice, and lover. She came from Coos Bay in Oregon, randomly met Holder in January of 1972 when he knocked on her San Diego apartment’s door looking for her roommate. Kerkow’s involvement with the Black Panthers did not come across as a commitment on her part to the cause but a result of her rebellious personality.

Holder and Kerkew dropped half of the passengers in Los Angeles and the other half in New York, where the plane refueled before taking off for Algiers without any passengers. In Algiers and Roger and Cathy secured their $500,000 ransom. Holder, however, was not enamored by what he experienced in Algiers.

Upon Holder’s arrival with Kerkew, Algerian government officials quarantined the couple and their ransom. After long interviews and investigations with security services, Cathy and Roger were released to the Black Panthers but the money stayed in the custody of the Algerian state until a meeting with President Boumediene was arranged. Boumediene was on an official visit to Senegal. When he returned, he summoned the couple to the presidential palace. Koerner documents that despite Holder’s deep struggles with racial injustices in the US military, the President quickly dismissed him and Cathy as pedestrian trouble-makers rather than visionaries. The cash ransom was sent back to the US, but US requests to extradite the couple were rejected, and political asylum was granted to both of them.

Eldridge Cleaver was revolted that Boumediene took away the money that belonged to the revolution. This frustration was further escalated by a similar event, when a Detroit-based group commandeered Delta Airlines Flight 84 along with a one million dollars ransom to Algiers on July 31, 1972. Cleaver tried to beat Algerian security officials to the Maison Blanche Airport (now named after Houari Boumediene), aiming, to no avail, at instructing the highjackers to not part with the cash. The money was once again returned to the US.

Cleaver, frustrated, decides to address “Comrade Boumediene” in an open letter presented at a press conference despite his second-in-command Pete O’Neal advising him not to. Cleaver insisted that “the Afro-American people are not asking the Algerian people to fight our battles for us. What we are asking is that the Algerian government not fight the battles of the American government.” Boumediene was, as O’Neal feared, insulted by Cleaver’s words and responded not only by having dozens of soldiers raid the International Sector residence and haul away telephones, typewriters and AK-47s, but also by asking Cleaver to step down as head of the International Section.

From Boumediene’s perspective, the Algerian government was a generous host to the Black Panther Party. It allowed it to operate openly and freely, supported it politically and financially (disbursed monthly stipends thanks to petro-dinars), and ran the risk of severing its business (gas and oil) deals with (among others) American companies. From this point of view, the Black Panther Party had to demonstrate, in action, what it said it was there to do. Earning the money needed for the mission (rather than relying on skyjacked ransoms) was a necessary if basic step.

Yet, the Algerian government was not alone in its disenchantment with the Panthers’ International Section leadership. Indeed, when Cleaver accepted to step down as leader of the party and turn it over to O’Neal under the ultimatum presented by Algerian authorities, Holder was aghast and loathed Cleaver for this for a long time. Shortly after, O’Neal and his wife left Algeria to find greener pastures in Tanzania. (O’Neal, incidentally, would go on to gain some minor celebrity as the subject of his time in Tanzania, “A Panther in Africa.”) O’Neal named Roger Holder as the head of the International Section who eventually also left with Cathy for France.

Kerkew’s whereabouts remains a mystery. The couple seems to have separated in Paris where Cathy abandoned the Black Panther cause in favor of living a bourgeois life among French artists and celebrities. To this day, it is not clear what had become of her. Brendan Koerner closes the book imagining her in Paris living the kind of American Dream that could only be lived if America was left behind.

Algeria’s legacy for supporting international revolutionary causes can still be seen today in the country’s continued stand on the Palestinian cause and on Western Sahara. Yet its record on questions of race and attitudes towards blackness, especially as manifested in its practices with regards to migrants and refugees from neighboring Mali and Niger, is so poor it’s hard to imagine a time when Black Panthers roaming the Casbah or the spirit of the famous Pan-African festival of 1969 filling the streets of Algiers were a common thing.