Key and Peele Unchained

Sean has blogged here before about the American sketch comedy duo Key and Peele. Around the same time I also came to learn about them after a friend had introduced me to the show. Before giving it to me, he said “it’s like Chappelle’s Show but for today.” These words rang in my ears for days. Dave Chappelle’s straight talking commentary on racial disparity in America combined with goofy abandon was a joy to watch, and honestly, just damn funny. Would Key and Peele be like Chappelle or better?

Key and Peele is framed as a smart sketch show on race relations in America by two “bi-racial” men Keegan Michael Key and Jordan Peele (they both have white moms, they tell us). I found most of their skits funny, but lacking the ballsy commentary and unashamed black perspective that Chappelle’s Show had. However, it was their slavery skit, and the piece preceding it that really annoyed me. Here’s the sketch:

What’s not included in the video above was their introduction to the live studio audience where Peele announces: “OK, so Africa is a fucked up place.” To which Key, seemingly surprised, responds in a disingenuous defense of Africa: “You wouldn’t want to see the Nile? The plains of the Serengeti?” Which is really just the vehicle for which Peele’s lambasting can continue: “You have flyover states. Now, to me that’s a flyover continent.” And the pièce de résistance: “Slavery was an awful thing. Silver lining? It got my ass out of Africa.” The follow up to which was the skit depicting two slaves who get increasingly jealous that no one is bidding for them at the slave auction.

At least in Django Unchained the slave traders got shot (cc: Spike Lee).

Part of the critique of Key and Peele has been that they are “edge-less” and very self-conscious to not offend anyone. Yet, how come they seem to have no qualms in making Africa the butt of an ignorant joke? Is our offence not taken as seriously? Is it really worth it to bring up something as painful and criminal as slavery when the joke is still on the black guy? Why even go there?

Comedy Central clearly seeks to fill the void left by Dave Chappelle when he famously walked away from his wildly popular show (and a $50 million contract!) in the middle of the third season. He claimed that with the $50 million came huge pressure and interference from the network. While Key and Peel frame themselves as “bi-racial” and thus able to occupy both black and white spaces and identities, black people bear the brunt of their humor in all of their skits. White supremacy isn’t questioned at all, while black masculinity is fair game. Which makes you wonder, who is their actual audience? What strings are Comedy Central pulling behind the scenes? Again, Kartina Richardson said it best when she wrote of them in Salon: “Key and Peele fail to ever address the violence of racism, literal or figurative, and this timidity leaves their material lifeless.” In other words, get real about social disparities, and your work will be funnier.

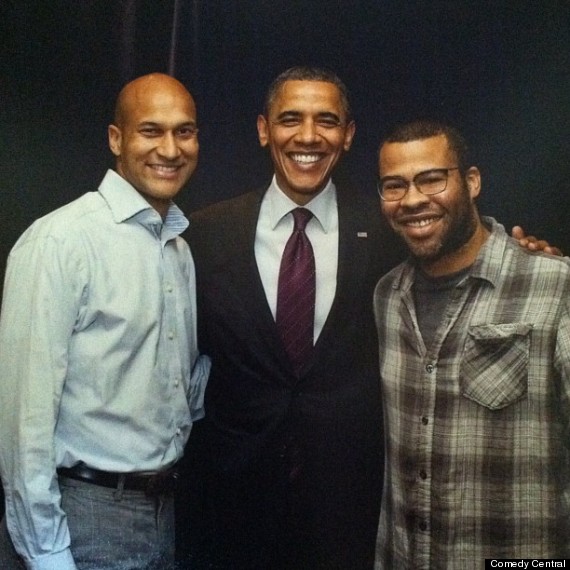

The show has done exceedingly well, with an endorsement by US President Barack Obama himself (after watching their skit of Obama needing an anger translator, which is actually pretty funny and rings true) and they have recently announced a third season. Let’s hope in the future they are able to get to the root of the issues they make fun of: black masculinity, slavery, and racism; and then make fun of that.