The geography of a storm

Hurricane Melissa made clear what COP30 obscures: the climate crisis still follows the lines of empire.

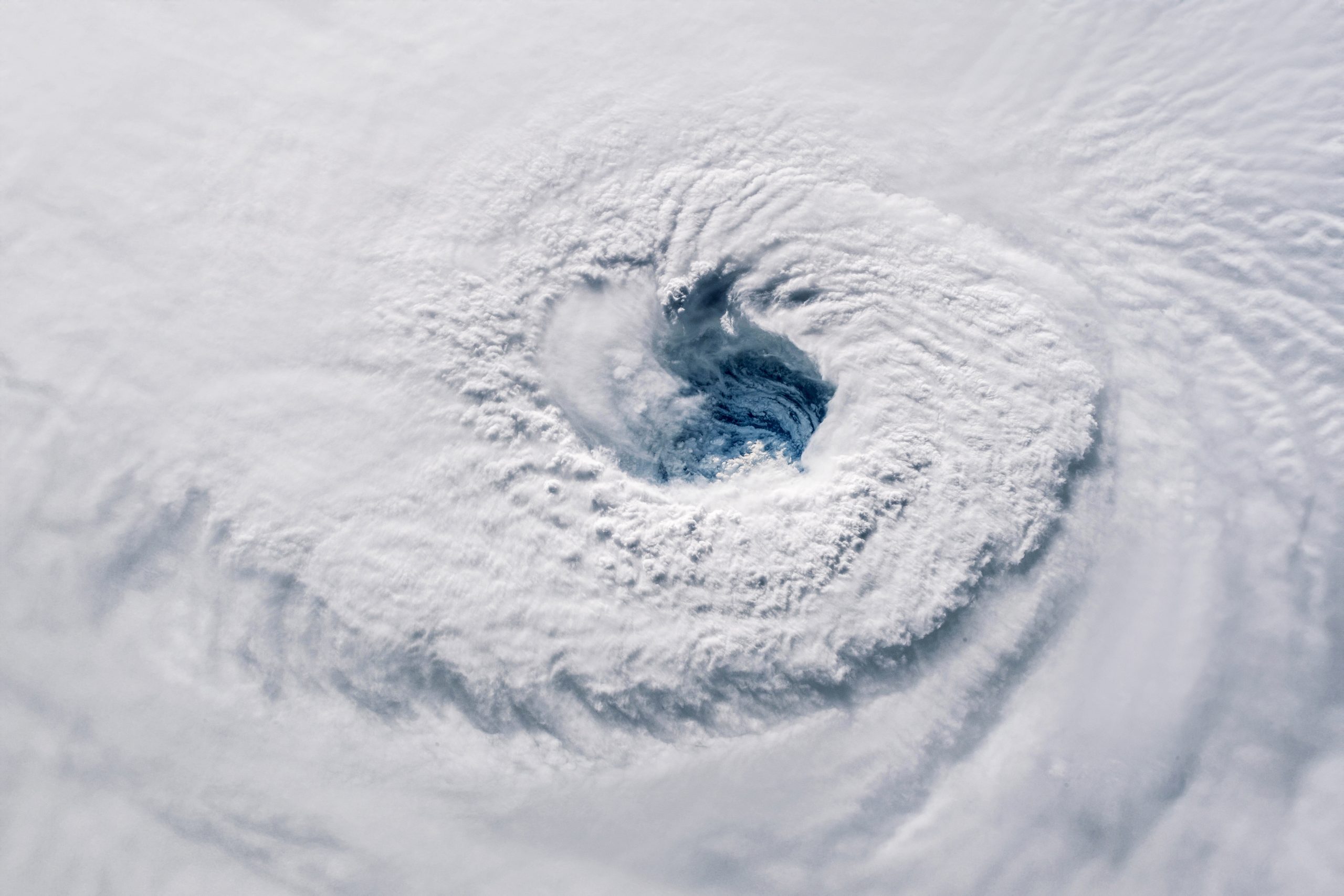

Hurricane Melissa, 2025. Image © Alones via Shutterstock.

Last week, Hurricane Melissa struck Jamaica, Haiti, and Cuba. The full impact is still uncertain; the water has yet to recede. Videos circulating online show torrents tearing through streets, cars swept away, homes submerged under rising floodwaters. So far, more than 50 people are reported dead—but that number will likely climb once the storm calms and communication lines are restored. In Jamaica alone, more than 2.8 million people are without electricity. “There is no infrastructure in the region that can withstand a Category 5,” the Jamaican prime minister warned before the storm made landfall.

The region’s infrastructures are designed for extraction and export—systems that enrich others while leaving the islands exposed. They are not built to protect people against devastating climate events. So, after the worst hurricane ever recorded on Jamaican soil, how are they supposed to rebuild? How does a country already burdened by debt and austerity recover when every rebuilding effort is financed through the same global structures that made it vulnerable in the first place? This is the paradox of postcolonial climate disaster: those least responsible for the crisis are expected to reconstruct their ruins with the tools of their own dispossession.

Ironically, all this unfolds as world leaders and environmentalists prepare for COP30—just days away—where climate justice will once again be declared a global priority. Yet following Hurricane Melissa’s devastation across the Caribbean, silence reverberates across the very networks that claim to fight for the planet. Greenpeace, for example, has not issued a statement on the hurricane; instead, today its feed commemorates the first anniversary of the floods in Valencia. Both are symptoms of the same accelerating climate crisis, but their unequal visibility reveals how environmental concern continues to follow colonial lines of empathy. This is far from “new.” As Nathan Hare argued in his 1970 essay Black Ecology, mainstream environmentalism has long centered the concerns of white and affluent societies while ignoring the toxic realities of racialized environments. Half a century later, that critique still holds: climate concern too often stops where empire begins. What we witness with Hurricane Melissa is precisely that continuity: an environmental politics that can mourn melting glaciers but not drowned Black geographies.

For decades, Black and brown nations—including those of the Caribbean—have warned that the climate crisis is not an abstract future but a lived reality. From the Pacific Islands to the Sahel, from Philippines to Palestine, the Global South has been sounding the alarm long before it became fashionable to speak of “climate emergency.” Yet even as world leaders gather each year under the banner of the COP, the outcomes remain devastatingly unchanged. Indigenous leaders are invited to perform welcome rituals, young activists are photographed for glossy campaigns, and small-island states deliver pleas that vanish once the cameras turn away. After 29 COPs, what has truly shifted? What will be so different in this upcoming COP? Emissions continue to rise, fossil fuel subsidies persist, and the same corporations that profit from the destruction of the planet sponsor the negotiations meant to solve it. The theater of inclusion masks a structure designed to preserve the status quo.

So while leaders from the Global North fuel their private jets in preparation for COP30—ready to trade targets, pledges, and “green” solutions—the storm in the Caribbean is a reminder of what those conversations consistently erase. The language of decarbonization and greenwashing rarely names its colonial foundations; the frameworks of climate governance often avoid the term climate colonialism altogether. If they would look beyond their negotiation tables and into the lives of those in the Global South, they would see that climate change has been a daily reality for far too long. For many, it is not a crisis to come but an inheritance already lived: rising tides, poisoned air, and vanishing ground. What the North calls “adaptation,” the South has endured for generations in silence: without recognition, without reparations, and without rest.

Hurricane Melissa should serve as an alarm for those preparing to gather at COP30. Jamaica now faces the impossible task of rebuilding—its millions without power, homes and livelihoods erased in a single night, and the emotional wreckage of lives upended once again. Yet even as delegates board their flights to negotiate “ambitious” targets, what Melissa exposes is the terrifying normality of catastrophe in the Global South. These storms are no longer rare; they are the predictable outcome of a world still addicted to fossil fuels, overconsumption, and denial. If COP30 means anything, it must begin by reckoning with this reality: that every delay, every watered-down commitment, every empty declaration will translate into more flooded towns, more unlivable coasts, more grieving communities.