The architecture of power

Inside the crumbling walls of Nigeria's Old Secretariat, echoes of colonial governance and national awakening meet the silence of decay.

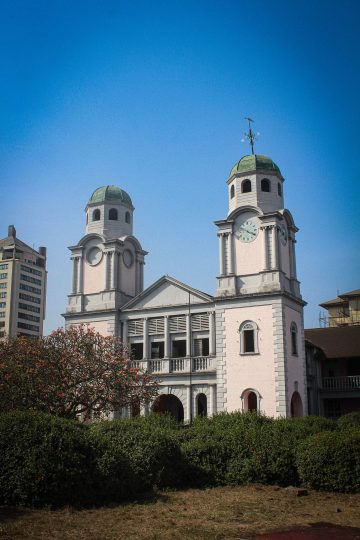

Central Portion of the Colonial Secretariat. Image credit E. H. Duckworth © Northwestern University, Illinois.

Nestled along the Eastern end of the Old Marina, amongst buildings erected around the same architectural, associational, and political period, stands a crumbling structure many walk and drive past without a second glance. But in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this building—the Old Secretariat—was the administrative and legislative heart of colonial Lagos. The everyday Lagosian or Nigerian would catch a glimpse of it whilst driving on the Ring Road section at the Outer Marina.

The Old Secretariat was not just a testament of British political domination but an architectural rupture in the skyline of Lagos Colony at a time when Afro-Brazilian structures and traditional Yoruba houses dotted many parts of the colony. It served as an architectural masterpiece for its time, and even in our day—as well as the seat of colonial administration, where decisions were made, for good and bad. The bad included the appropriation of lands owned by “Natives” in 1909 and 1910, as well as the creation of the Colonial Church—both moves were seen by Nigerians, and especially members of the C.M.S. Christ Church Marina, as racist and brewing segregation within the society and earned the condemnation of notable nationalist leader Herbert Samuel Heelas Macaulay, as well as other prominent figures.

The Old Secretariat (then known as the New Secretariat) was constructed between 1891 and 1893 to provide a centralized location for key government offices, including those of the governor, deputy governor, chief secretary, and other senior officials. Initially estimated to cost £500, the final expenditure amounted to £764 5s. Designed by the Public Works Department (now the Federal Ministry of Works and Infrastructure), the building embodied a distinctly neoclassical style that reflected British ideals of order and authority.

Its façade featured a main entrance framed by voussoirs, a keystone, Doric pilasters, and dentils, while the twin towers incorporated open frames reminiscent of Cape Dutch architecture. The second floor displayed a central pediment bearing the British coat of arms above the Legislative Council balcony, supported by five Ionic columns on stylobates. Above this rose the twin towers with an entablature comprising architrave, frieze, and cornice, and paired Ionic pilasters that served mainly decorative purposes. Crowning the structure was a cupola—a dome-like feature typical of the period—used primarily for ornamentation, completing the building’s imposing statement of colonial power and prestige.

These architectural features were not merely decorative but also symbolic. The neoclassical design, with its columns, pediments, and symmetry, reflected the ideals of order, authority, and permanence that the British Empire sought to project in its colonies. The grandeur of the Old Secretariat’s façade contrasted sharply with the living conditions of most Lagos residents at the time, underscoring the visual and spatial expression of colonial power. Its design communicated the dominance and prestige of the colonial administration, making the building both a functional seat of government and a physical statement of imperial control and ambition.

The Legislative Council Chamber, housed in the central part of the second floor of the building, just above the first floor lobby, was most likely occupied from the mid or late 1910s up till the time when the National Assembly at the Racecourse (now Tafawa Balewa Square) was built (partly on the site that was once housed Godstone House—the eclectic home of Sir Kitoyi and Lady Lucretia Layinka Ajasa).

The Legislative Council Chamber in a British colony was mainly responsible for governance and lawmaking, where appointed or later elected representatives met to debate and pass laws under the authority of the colonial governor, who represented the British Crown. The council debated bills, amended them, and either passed or rejected them, with final assent coming from the governor on behalf of the monarch. It also advised the governor on governance matters, though the governor often retained overriding power. In addition, the chamber discussed and approved colonial budgets, including taxation and public spending, though financial control remained largely with the colonial office in London. Membership varied by era, with members appointed, nominated, or partially elected, but representation of local people, especially Africans or indigenous groups, was minimal and mostly symbolic. The council also served as a tool of colonial control by co-opting local elites, creating divisions between pro-British figures such as Henry Carr and anticolonial leaders like Herbert Macaulay, thus giving the appearance of inclusion while real power remained in British hands.

Between 1927 and 1931, the Legislative Council, operating from the Old Secretariat played a key role in the creation of the Lagos Executive Development Board, an important agency that spearheaded slum clearance on Lagos Island and the development of the Yaba Garden Estate to ease overcrowding. At a 1927 Council meeting, Hon. Eric Moore questioned the effectiveness of the Yaba Scheme and urged the government to fund swamp reclamation on the island to create more building sites. The chief secretary disagreed with the claim of failure and confirmed plans to use a new reclamation plant for future works on Lagos Island. In this Legislative Council, there were four elected positions, one seat representing Calabar and three seats representing Lagos. Seven other seats were for appointed members which included Samuel Obianwu, Sir Kitoyi Ajasa, Samuel Herbert Pearse, E. H. Oke, Mark Pepple Jaja, I. O. Mba (representing the Igbo Division), and Isaac Thomas Palmer (representing Benin and Warri Division)

In late 1928, discussions in the Legislative Council reflected growing concern about health and urban conditions in Lagos, alongside efforts to address overcrowding through the Yaba Garden Estate scheme. The estate represented one of the colonial government’s earliest attempts at planned suburban housing, intended to decongest central Lagos and promote healthier living conditions, a key step in the city’s early urban development.

Although the Yaba Township debates might seem tangential, they are significant because they capture the kind of major urban and public health decisions that shaped colonial Lagos, many of which were deliberated and authorized within the Old Secretariat. The discussions on the Yaba Garden Estate between 1928 and 1931 highlight how the Legislative Council, meeting in this building, sought to confront urban overcrowding, sanitation, and housing shortages in Lagos. These debates reflect the colonial administration’s early attempts to plan suburban expansion and social engineering through land policy and segregation, core aspects of Lagos’s transformation in the late 1920s and 1930s.

By tracing these deliberations, we see that the Old Secretariat was more than an administrative office; it was the site where key policies influencing Lagos’s physical and social landscape were conceived. Yet the same patterns visible in those discussions, such as bureaucratic inertia, limited public accountability, and the neglect of long-term maintenance, also foreshadowed the decay and disuse that would later affect the building itself.

The Legislative Council served as a foundational structure in Nigeria’s political evolution—bridging colonial administration and the emergence of national governance. Initially dominated by appointed colonial officials and elite collaborators, the Council gradually opened up to more formal and democratic participation, with the first elections held in 1923. Over time, representation expanded beyond Lagos to include elected members from Calabar and, eventually, other regions of the country. This shift signaled a slow but significant move away from exclusive colonial rule toward a more inclusive legislative process—laying the groundwork for the Regional Houses of Assembly and, ultimately, the central National Assembly. The debates, tensions, and reforms within the Legislative Council reflected Nigeria’s early struggles for representation, autonomy, and the reimagining of governance on its own terms.

The Council Chamber was most likely not in use from 1955 to 1956 when the new National Assembly building was completed and the Assembly’s daily activities had to be moved to the Race Course. By 1954, the Lyttleton Constitution made Nigeria a federation with separate regional legislatures and a Federal House of Representatives in Lagos, creating the need for a new federal chamber. During the transition, the House met temporarily at an adjoining building in the Old Government House in Marina, while the older Legislative Council continued sessions at the Old Secretariat. This division reflected Nigeria’s political evolution, the Secretariat symbolizing colonial governance, and the new Race Course National Assembly, completed in 1956 and opened in 1957, representing the emergence of national self-rule and later hosting the landmark independence debates of 1960. It is largely unknown that the course of Nigeria, her fate and destiny, was once decided on a regular basis in the confines of this historic structure. Despite the history attached to the Old Secretariat, it has been overlooked by the government who, despite declaring it a National Monument, have left it to its current state of degeneration. The rear section of the Old Secretariat once housed a section of the Public Archives, but its documents pertaining to Nigeria’s history had to be moved to another location as a result of disrepair in that section.

From the 1890s to the mid-20th century, it hosted legislative debates and decisions that shaped Nigeria’s early political journey. Today, its fading structure reflects a broader national disregard for historical preservation. Behind its age-long derelict state lies a broader question: What becomes of a nation that forgets the spaces that shaped its political and social evolution?

With efforts from civic groups like The Creative Alliance, the National Commission for Museums and Monuments (the federal agency tasked with responsibilities pertaining to historic sites and monuments), and others working to document and preserve this history, there is hope.

The Creative Alliance, an interdisciplinary collective of artists, historians, designers, and cultural practitioners, launched the TALE project to explore how historic sites can be reactivated as living cultural spaces. In July, the project hosted a two-day exhibition at the National Museum Lagos, bringing the Old Secretariat’s layered history into focus. The exhibition featured archival images, historical research, photography, sound design, and an immersive digital experience inspired by the Secretariat’s grand entrance and lobby. Oral histories from those connected to the building’s past added personal narratives to the story, while fireside conversations with architects, historians, and cultural workers invited the public to consider not only what the building once represented but what it could become. This multi-sensory approach sought to preserve the building’s memory while sparking dialogue about how such spaces might be reimagined for artistic activation, cultural education, and civic gathering.

In a conversation, Seju Alero Mike, the project coordinator and creative director of The Creative Alliance, highlights that “our work on the Old Secretariat began as both an act of remembrance and a call to possibility; to see this structure not only as a relic of colonial administration but as a living site capable of hosting artistic and cultural activation.”

She goes on to say: “We believe that spaces like this hold memory and potential in equal measure. By bringing artists, historians, and communities into dialogue with its walls and archives, we aim to preserve its layered history while proposing new uses that benefit the public. It is an opportunity to turn what might otherwise remain an abandoned monument into a space for creative practice, cultural education, and civic gathering. Our hope is that by documenting, interpreting, and animating the Old Secretariat through artistic interventions, we contribute to a wider culture of memory in Lagos; one that values its historic spaces and invests in their renewal. Projects like these not only safeguard heritage but also invite people to imagine new futures from old foundations.”

Yet such initiatives require broader public support and sustained governmental action. Lagos—and Nigeria—must decide: Will we continue to walk past our heritage until it collapses under silence, or will we begin to look again, with care, urgency, and intention?