From Kampala to Soviet Kyiv—and back

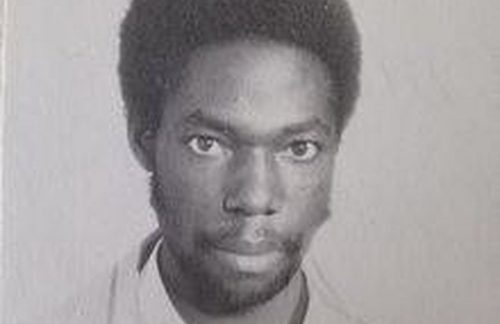

The Ugandan architect, Stephen Mukiibi, reflects on his studies in Soviet Ukraine and the lessons he learned on equality, environment, race, and friendship.

The Faculty of Architecture, Institute of Construction, Kyiv, 1987. Photo by Oleksandr Ranchukov.

- Contributors

- Stephen Mukiibi (SM)

- Łukasz Stanek (ŁS)

- Oleksandr Anisimov (OA)

In the wake of decolonization, many African leaders exploited Cold War rivalries in order to extract resources for modernization and development. Architecture, planning, and construction were at the forefront of the Soviet and Eastern European offer for Africa. From the early 1960s, state-socialist institutions designed and constructed multiple medical, educational, cultural, and sports facilities as well as housing and industrial plants across the continent. Some of these buildings were highly visible gifts for countries pursuing the socialist development path, such as Ethiopia during the Derg regime, while others were bartered for raw materials, sometimes with governments hostile to socialism. The socialist countries also supported architectural education in Africa, both by sponsoring universities on the continent and by offering scholarships for Africans to study in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Among the recipients of such scholarships was Stephen Mukiibi, who in the 1980s studied architecture at the Kyiv Institute of Engineering and Construction (known today as the Kyiv National University of Construction and Architecture) in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

I am an urban scholar based in Kyiv. I am currently working on a project called “After Socialist Modernism,” which addresses Soviet Ukrainian architecture and architectural education and connects them to post-socialist urban transformation.

Thank you for that introduction; let me also introduce myself. I come from Uganda and I’m an architect, scholar, and educator. I was trained in Soviet Ukraine, and I still have good memories of my time there. At that time, I entered adulthood and I was forming my tools as a professional. I have good memories of Kyiv—I miss it in a way—and I don’t regret studying there. Afterwards, I returned to Uganda, then I continued my studies in the UK, and after my training there I came back to Uganda. I joined academia and that is where I am now.

I first arrived there, in Kyiv, into the field of architecture, with almost no previous experience nor any idea of what it was. By then, the Soviet Union was giving bursaries for studies in different areas based on the students’ performance in physics, math, and chemistry, and I was selected. Initially, I was going to study engineering in Uganda, as architecture was not being taught in the country. The only architects in Uganda were those who had been trained in Nairobi or countries in the West. We also had a few Ugandan architects trained in the Soviet Union—in Russia, Ukraine, and other republics.

What year did you come to Kyiv?

I came to Kyiv in 1983, by the end of the year. Then I started a yearlong preparatory course, and in 1984 the actual studies started. I graduated in 1990.

Did you know Russian?

No, I didn’t. I had a few colleagues who had studied a bit of Russian. Ugandans who went to the Soviet Union for training did so through two different channels. There were those who, like me, applied for a scholarship through the government of Uganda and the Ministry of Education. Others applied through the Russian Cultural Center in Kampala. They often had received some training in the Russian language and in Russian culture.

The first year was the year of preparation: they taught us the language and took us through the subjects, including those relevant for the profession. And so we had some mathematics, physics, chemistry, and a few other things. We also received some training in the fine arts, drawing, and sculpture.

Who participated in the preparatory course?

We had fellow students from Latin America and Africa. We learned about the history and culture of the Soviet Union. It was also … a bit political.

How so? Were political topics part of the curriculum?

Yes, they were part of the whole thing, because you had to be introduced to the basics of what Karl Marx wrote about the socialist system. Since this was the time of the Cold War, it was important for the Soviets to communicate their position. I think that this included the expansion of their influence to other countries, in competition with the West.

How did you think about why you were there? Did you see yourself as part of this Cold War competition?

I think that we had mixed feelings about it. We were not very sure about the whole thing, but as time went on you could see the competition between the East and the West. We also saw that Soviet assistance to Africa was part of this competition. But at the same time, we were appreciating the fact that we could study for a profession, which we had to focus on.

The Soviets were competing with the other system, and therefore they were trying to show that their system was better. So you had to listen and to think about it. … I did try to compare what I saw with what I had gone through since my childhood, and it was a challenge, but it also gave me another perspective. Remember that the country where I came from was basically a capitalist state, but it was not an advanced country. So we were not advanced within capitalism, and then I was told about socialism and communism, and how they came about, and how they were going to be. So I was wondering: was communism our future? I was really wondering about that. What is interesting to me is that I had an opportunity to see the two sides of the coin, and I can appreciate the good and bad sides of each of the systems.

During the 1980s, many Western critics challenged the tradition of modernist architecture. Was this also the case in Kyiv?

Yes, that discussion was going on, and it was interesting, because some teachers referred to it as a way of explaining how the socialist system was possibly a better option. Not everyone participated in that discussion, but a few professors were following it and talking about it.

Was that critical view directed at Soviet architecture too?

Not really; that wasn’t there. Nonetheless, a number of Soviet students expressed their views guardedly, criticizing architecture in the Soviet Union as monotonous, ideological, and lacking the expression of freedom of opinion. Otherwise, in lectures, the professors used to discuss Western architecture with both fair and unfair criticism.

You were studying in Kyiv, the capital of Soviet Ukraine. Was the question of national identity or specificity discussed?

Do you mean the issue of the national identity of Ukrainians versus the USSR?

Yes.

It was not evident, and it was not openly discussed. The message was that the USSR was a unified, single country. And you couldn’t easily see the differences until you interacted with a few of your colleagues. For example, in the hostel, I shared rooms with Soviet students from other republics. And a few of them could tell you about these differences. There was a feeling that the Russian influence was overshadowing others. As far as the difference between Russian and Ukrainian culture was concerned, it was there but latent; you couldn’t really see it on the surface.

What about Soviet Central Asian republics?

I had lectures about their architecture in class, but my exposure to this region was not big.

Were architecture and planning in Africa discussed at all?

There was a bit of that, but not in detail, because of the scarcity of professionals who had experience in Africa. There was more focus on northern Africa because some among our teachers had longer interactions with those countries and gained more knowledge about them. But discussion about sub-Saharan Africa was really limited.

Soviet scholars published a couple of books on architecture and urban planning in tropical climates; for example, Rimsha’s Gorod i zharkii klimat [The City and the Hot Climate]. Were you aware of them?

Yes—not exactly this book, but others going into that direction were there. Our teachers were telling us about architecture in different climates: hot and humid, hot and dry. … They were also telling us about the general principles of design in response to climate.

When you were working on your designs, did you choose locations in Uganda or in the Soviet Union?

From the first to the fourth year, we did projects based on locations in the Soviet Union, but for the final year project we were given the option to choose, and I chose a location in Uganda, in the town of Jinja.

What kind of feedback did you get on this project from your tutors?

They didn’t know that place; they had never been to the country like that. They were aware, though, of the crucial requirements of design. But I had colleagues from Uganda who were also in the same program, who were ahead of me, and one of them [Professor Barnabas Nawangwe] is now the vice-chancellor of our university. They used to go home and come back and get some of the information I would require, including situation plans, demographic data, building regulations, and so on. I got these pieces of information from them, and I could discuss them with my professors. Environmental questions were high on the agenda, and we discussed them a lot, which I appreciated. When I look back, it is striking to me how much we focused on these environmental issues—which are so important, as today everybody understands.

Did you travel in the Soviet Union during your studies?

The training was done within Ukraine, and we moved around within Ukraine. But during holiday times we had the opportunity to travel. I don’t know how it is now, but traveling was cheap back then. Actually, that was one of the advantages of studying in the Soviet Union. Once you learn the language, you could move anywhere and get exposed to new things. So we managed to travel to Leningrad, Odessa, and Tashkent. But that was our own initiative, not part of the course.

Did you go on these trips alone or with your fellow students?

There were times I traveled with African students, and a few times I traveled with my Russian friends. They took me to see some places.

Did you feel the difference in architecture across various places in the Soviet Union?

Yes, to some extent. Of course, you could feel it when you traveled, for example to Moscow, which was different from Tashkent. But Soviet planning meant that there was not much difference in architecture. This was interesting for me: the fact that there was something common in architecture. They tried to provide common services and facilities which could be more or less replicated across the Soviet Union. There was something monotonic about these facilities, being constantly replicated.

Did you see this monotony as a bad thing?

In one way, yes, because you wish to see more variety, more creativity. But when I look back, I can understand it as a cost of solving the problem of the multitude. It was about numbers: how to ensure that everyone was provided with a minimum of services. In that case, of course, you can lose some creativity. The second thing was that this repetition could have resulted from political decision-making, starting with ideas of what was preferable or desirable, but also involving restrictions on alternative solutions.

How do you remember your everyday experience in Kyiv?

I would say that it was a rich experience. I had very memorable, good moments, and I also had bad moments. You could face serious racism from some individuals, but you also had friends—good friends—who would always protect you and guide you in many ways. During the first year of training, we were living as foreigners, alone. But we came from different countries, and I could learn how different people lived. And when I started the first year of my architectural studies, that was also when I started living with Soviet students. I could learn more about them, and I had an interesting time. It had some challenges, especially when you go to some places and find that there were those who called you “monkey.” But after living in many other places, I found that those things happen. What is more important is to meet those who accept you, and consider how they do accept you. Do they accept you as an individual? Someone you can trust and relate to? And I had that. All those years affected and shaped me, because those were my young years, and it was the first time I went away from home and became independent. It was a good experience.

Did the authorities react to these racist incidents?

You see, it wasn’t something that was accepted in the society, as far as the Soviet Union was concerned. But what can you do if someone on the bus does that? There were a few cases when someone reported incidents to the police, but nothing was done. Or you found that the policeman was also of that nature, so you let it go. Still, we had friends that could stand up for us. But on the other hand, because the Soviet Union was trying to sell itself to the outside world and to the developing countries, racism was rebutted. It also happened that someone who was found to be doing this was reprimanded.

Did such incidents also happen at the university?

There were a few incidents with students and teachers. For example, I’ll tell you the story about a colleague from the preparatory course. He wanted to go in for a swim, and the moment he entered the swimming pool, other students moved out. He found it funny, of course, and just continued swimming. Those incidents could happen, and it would depend on the administration how such cases were handled.

How did you make sense of this behavior? Especially in view of the official Soviet position of antiracism?

I saw it as very unfortunate, because the official message was different. I realized that you have to be a bit careful how you move around and conduct yourself in public, because you could experience certain things of that nature. But on the other hand, it also varied from place to place. And now, when I look back, I know that racist people can be found in any country, and that is something you can’t argue about. But as far as the Soviet Union was concerned, the reality was a bit different from the official position.

Did you travel abroad?

Yes, during our holidays we traveled to other parts of Europe. That was a time when I had the opportunity to travel and see other parts of the world. There was limited possibility of traveling for the Soviet people, but as foreigners we had that opportunity. So we used to travel to Europe and see what it was like. And you could feel the difference, especially the moment when you moved out of the Soviet Union. While [East] Germany was still a bit the same, after leaving Eastern Europe you could feel the difference. And it was quite remarkable.

Where did you travel?

To Spain, the UK, Germany—East Germany at that time. I traveled to some countries of Eastern Europe as well, including Poland.

Traveling to Western Europe must have been expensive.

By that time, it wasn’t. This was one of the things that were interesting in the Soviet system. Russian currency was cheap by that time. We were given a stipend, which was enough for us in terms of food and also some extras. And foreign students could also benefit from illegal dealings. You could buy a few things in the West that were not on the market in the East, and if you found someone who bought that item, you could earn some extra money. Some people were very involved in that. I also had an opportunity to work in the UK, as I had a cousin there, and then I would come back to Kyiv and life would continue.

Have you stayed in touch with anybody?

Unfortunately not; that’s the part which I regret. What happened was that when I finished the training, I went to see my cousin in the UK. And I lost my suitcase with all the contacts, and I never got it back. The only contacts I have are of the other Ugandan colleagues who also studied in Kyiv.

After your move to the UK, you studied in Newcastle. What was the difference between your studies in Kyiv and your studies in Newcastle?

Newcastle, actually, was a bit later. I first came back to Uganda and joined the University as a junior assistant lecturer. Later on, I applied to the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, and I enrolled into a short course. Afterwards, I pursued a master’s course, then another master’s, and then a PhD. Of course, there was a difference in culture: the level of openness to certain things was different. I do appreciate having had that wide exposure, that comparative experience—unlike a person who studied architecture from year one in the UK, for example. Nevertheless, I also saw that there was something in common in the former Soviet Union, and Europe, even in America: there was little knowledge about Africa. I met only a few professors who had worked in Africa and had very good knowledge about the subject. And working with those professors made my studies much more complete.

Stephen, thank you so much for agreeing to talk to us. Let us introduce ourselves briefly: I’m an architectural historian at the University of Manchester. I have recently written a book, titled Architecture in Global Socialism, focused on the Cold War-era architectural exchanges between the socialist countries in Eastern Europe and the decolonizing countries in West Africa and the Middle East.