It’s Not Just About Cecil John Rhodes

Statues of icons of colonialism continue to exist in their visibly unaltered state throughout South Africa’s major cities.

In the past week I received an email from my alma mater requesting the University of Cape Town (UCT) alumni to comment on its Student Representative Council’s calls for the sculpture of Cecil John Rhodes to be removed from its prominent position on UCT grounds. The email reads: “… Twenty years into our nation’s democracy, it is clear that the UCT community now needs to make a decision on whether this statue should continue to occupy such a prominent place, both on our campus and in the landscape of our identity as a South African university on the continent of Africa. The legacy of Cecil John Rhodes undeniably forms an inescapable part of our history. The question we must now ask ourselves is whether he should continue to be venerated in the manner in which the statue presently seems to do. Can we continue to memorialize him in this symbolic way, while being committed to transformation? Can we create a more inclusive and diverse university community — one that is sensitive to the role that Rhodes played in the history of our country, and our continent?”

Max Price, the vice chancellor of UCT has since revealed that his proposal to remove the statue has been supported by the institution’s senior leadership group (SLG), but in light of important debates that have emerged over the past few weeks, I question whether this is the best approach. I am writing this from my current university where until very recently a bronze plaque with a dedication to the former South African prime minister and ‘architect of apartheid’ H.F. Verwoerd graced the entrance walls of a prominent building on campus (the building was partially destroyed by a fire in February) and where later this year I will attend my graduation ceremony in a hall named after another former apartheid prime minister, D.F. Malan. Given this current context, I welcome the vice chancellor’s efforts to critically engage with pleas from the student body to have the statue removed. The Haitian historian, Michel-Rolph Trouillot reminds us that “all facts are not created equal: some leave physical markers, others do not … What happened leaves traces, some of which are quite concrete – buildings, dead bodies, monuments, political boundaries that limit the range and significance of any historical narrative”.

While I agree that material culture is both embedded with and transmits meaning as well as produces historic narratives, the university’s efforts shouldn’t simply be focused on the removal of the statue, as this may rob us of an important opportunity to track and expose the role of power in the making of history.

Those South Africans (and others) who don’t understand why celebrating and memorializing Cecil John Rhodes in the public landscape in the way we currently do is problematic or offensive, may need to revisit the country’s history and this requires digging a little deeper than the colonial narratives they may have been taught about men like Rhodes at school. Rhodes, who became prime minister of the Cape Colony in the late 1800’s was instrumental in the establishment of imperial laws that forced black people from their land to make way for industrial development — this formed part of the greater British colonial project which helped to disenfranchise the black population in South Africa — the consequences of which we are all familiar with today. I would argue that the sculpture gazing over the Cape Flats in its uncontested state, symbolizes the slow rate of transformation in the institutional, physical and socio-economic spaces of the Western Cape and in South Africa in general. In this regard, it is important for institutions like the University of Cape Town to recognize their role in maintaining systems of privilege that contributed to the lack of reform since we launched into Democracy in 1994.

In the transformation of former monument sites in South Africa, scholars like the Stellenbosch University-based historian Albert Grundlingh have commented on the ANC government’s low-key approach towards dealing with former symbols of apartheid (in terms of the removal and replacement of monuments). Grundlingh writes: “Apart from removing certain statues of H.F Verwoerd, prime minister from 1958-66, renaming airports and redecorating parliament, there has not been any concerted attempt to wipe the slate clean.” After the removal of the H.F. Verwoerd statue from the Parliament buildings in 1994, then president Nelson Mandela warned to use sensitivity in removing former Afrikaner symbols, saying: “[we] must be able to channel our anger without doing injustices to other communities.” Subsequent to the removal of the last 15-foot Verwoerd bust in Bloemfontein in 1994, which took several hours to pull from its perch, virtually no more changes were made to the material reminders of the old order in South Africa. Grundlingh writes that the ANC government has chosen instead “to reinscribe the past by developing its own legacy projects, so far eschewing huge monumental structures and opting for instead for practical, living, open museum sites. Robben Island is the Government’s flagship project in this respect.”

This hands-off approach to adjusting South Africa’s memory landscape is apparent in the way in which the icons of colonialism continue to exist in their visibly unaltered state throughout South Africa’s major cities. As the University of KwaZulu Natal scholar, Sabine Marschall writes: “… heritage officials in particular are well aware of the great importance communities in South Africa attach to their political icons and the heritage sector would hardly dare engaging in ventures that might undermine its widely perceived role as contributing to morally elevated societal goals such as community empowerment, reconciliation, education and nation-building.”

From 11 to 13 December 2013, the public viewing of former state president Nelson Mandela’s body took place at the Union buildings in Pretoria and was broadcasted live on SABC2, a national television channel. It was significant and symbolic to me (of the state of our nation) at the time that Nelson Mandela’s national memorial was juxtaposed with the unaltered visual landscape which reflected South Africa’s colonial and apartheid past. (A few days after, on 16 December 2013, South Africa’s national Day of Reconciliation, the South African State President Jacob Zuma, unveiled a bronze statue of Nelson Mandela at the Union buildings.) Sabine Marschall wrote in 2009 (and this became apparent while watching the 2013 broadcast of Mandela’s memorial) that no concrete guidelines or criteria had yet been developed in order to facilitate the removal of selected colonial and Apartheid era monuments: “The process of removal is acknowledged as being contentious and divisive, whereas the installation of new monuments is presented as an inclusive, unifying act, conducive to nation building and reconciliation” — which formed the basis of the national rhetoric of South Africa since Desmond Tutu coined the term “Rainbow Nation” in 1994. The results of this reconcillitory approach are reflected by current debates about our material pasts, sparked by UCT students which has erupted elsewhere in the country.

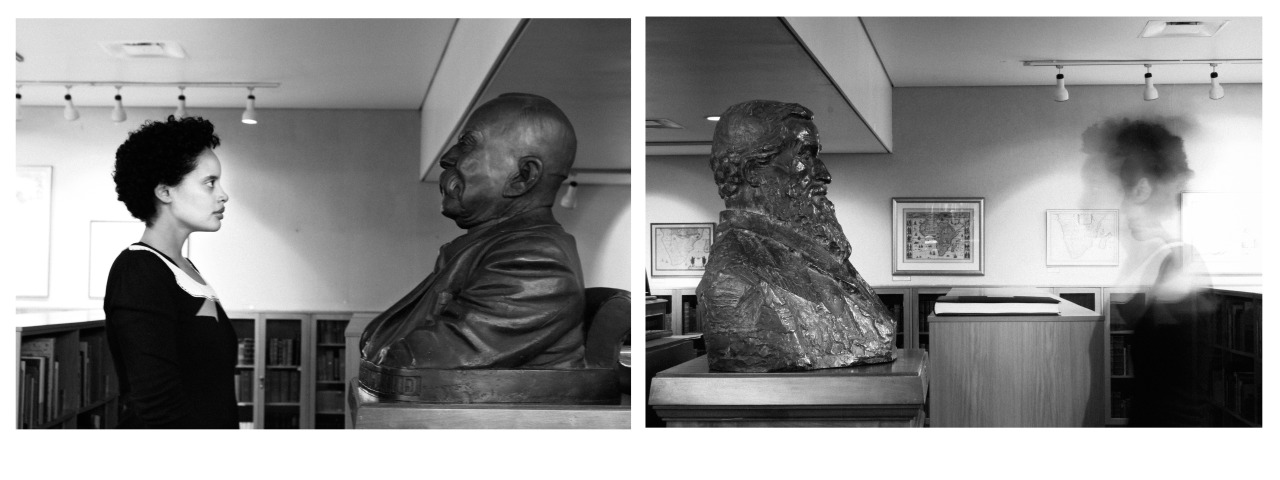

What’s clear is that the Rhodes sculpture at UCT (and similar sites elsewhere) needs intervention. There have been suggestions made by the UCT Vice Chancellor (the US equivalent is a University President) for a bronze plaque to be installed at its base to alter the heroic narrative around the Rhodes legacy in South Africa. Perhaps a better idea is to make the statue available for intervention by artists (via a transparent invitation and selection process) to disrupt the language and visual coding of the sculpture itself (in terms of materiality, scale and accompanying text) to permanently alter its meaning and the way in which it is read by present and future generations. The statue could become a reminder to the institution that there are pressing issues in terms of reform (beyond just removing it) that need to be addressed. My concern is that in ‘wiping the slate clean’ by removing the sculpture and placing it in the glass vitrine of a museum, far away from it’s context, an opportunity may be missed for continued dialogue about the lingering presence and effects of South Africa’s colonial past.