Where have the Chapungu gone?

What connects Zimbabwe’s chimurenga spirit, the disappearing bateleur eagle, and the stubborn afterlife of colonial capital?

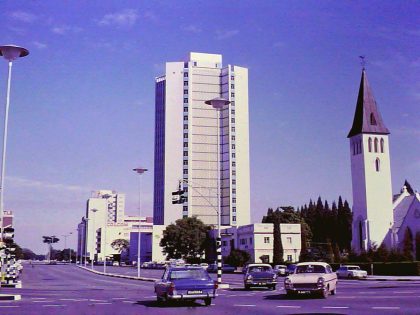

Photo by Glen Carrie on Unsplash.

This essay promises two things: crankiness and an absurd story. The first I cannot avoid, and the second I could, but I am drawn to this narrative arc. The story goes like this: Terence O. Ranger, the historian of all things Zimbabwe, died in 2015. Separately, sometime in the early 2000s, as Zimbabwe entered its ruinous era of currency collapse and social chaos, a species of raptor began to disappear across Zimbabwe. Again, separately, the revolutionary spirit that brought Zimbabweans to the brink of decolonization in 1980 seemed to fade. And, again, entirely separately, international investors siphoned profit out of Zimbabwe’s red earth. This narrative is true in spirit alone.

Terence O. Ranger was not the only historian capable of capturing southern Africa’s past. He was not the first, and he will not be the last, nor was he perfect. But he was a guiding light. Ranger guided historians of Africa with his prescience, not as if he saw the future but instead as though he sensed the history before he pieced it together through the archives. When you read his massive corpus today, you can feel his revolutionary spirit guiding him through Southern Africa’s most complicated events. This is why I warned earlier that this narrative is absurd. When Ranger died in 2015, the revolutionary spirit of Zimbabwe did not die with him. The author of the widely read Revolt in Southern Rhodesia (1967) did not have that power.

Chapungu, the bateleur eagle, has all but disappeared across Zimbabwe. This phenomenon has been explained by biologists in the most generic of ways: “[Like] other wildlife,” bateleur eagle populations have “declined rapidly” due to anthropogenic threats including “pesticide use and habitat loss.” But chapungu are not like other wildlife, because half a century ago, chapungu led Zimbabweans to victory in guerrilla war. This story could be told several ways—most commonly, chapungu embodied ancestral spirits during the liberation war. Or chapungu were animated by Mwari (God). Or both. No matter how the story is told, chapungu were eagles who assisted the people of Zimbabwe during their intense phase of violence.

The disappearance of chapungu in rural Zimbabwe has been explained two ways. Firstly, chapungu were no longer needed for guidance after the war was won in 1980 and Rhodesia became Zimbabwe, or secondly, chapungu, as ancestral messengers, gave up on Zimbabweans. Biologists believe that across Africa, the population of chapungu has declined by up to 79 percent since 1976. Just like the revolutionary spirit of Zimbabwe was neither embodied by nor died with its greatest historian, it would be absurd to say that the chimurenga spirit is in decline at the same pace as the exodus of chapungu.

Why waste all this time complaining about the speculative decline of the chimurenga spirit when Zimbabwe already became independent in 1980? Zimbabwe did indeed gain its independence from the Rhodesian Front’s breakaway colony in southern Africa, known by the same name from 1965–1979: Rhodesia. This victory was the end of a sort of knockoff apartheid in Zimbabwe, where land ownership, mobility, educational access, and voting rights were all tied to race. But in focusing on this victory, from Prime Minister Ian Smith’s Rhodesia, Zimbabwe was unable to gain independence from its original oppressor, the British South Africa Company (BSAC), or, in other words, international finance. This is not only true in theory—the specter of the BSAC haunts every aspect of the Zimbabwean economy.

The parcels of land that were first allocated to the BSAC’s original investors on the London Stock Exchange can still be seen on the map today. Take Border Timbers, owned by the son of the House of Schwarzenberg and Paradise Papers–named Heinrich Bernd Alexander Josef von Pezold. Border Timbers is an FSC-approved, “proudly Zimbabwean” timber company, owning 470 square kilometers and three mills. Border Timbers’ land in Chimanimani was central to the crippling $196 million court case against the Government of Zimbabwe that the von Pezold family won in the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) in July 2015, seven months after Terence O. Ranger left this Earth.

Border Timbers Ltd. is a remnant of land allocations (for the British South Africa Police, no less) under Cecil Rhodes’s BSAC, and has been owned by foreign investors since its establishment. Heinrich von Pezold’s father, Bernhard von Pezold, began purchasing colonial estates in Zimbabwe beginning in 1988, and as of writing, the family owns 78,275 hectares of agricultural land in Zimbabwe, producing timber, bananas, and most profitably, tobacco. Tobacco production accounts for approximately 50 percent of the total pesticide use in Zimbabwe. Biologists say that two of the main reasons for chapungu’s decline is pesticide use and habitat loss.

It would be absurd to suggest that the Austrian-Swiss-German von Pezold family is to blame for the disappearance of Zimbabwe’s most important bird, because this same story, of colonial holdovers in the international ownership of Zimbabwe’s wealth, is repeated across Zimbabwe. Rio Tinto Southern Rhodesia Ltd., for example, was re-formed as RioZim in 2004. It is now “wholly Zimbabwean owned,” because “friendly investors [are] granted Zimbabwean citizenship as part of the government’s efforts to lure investment.” RioZim, the parent company of RioGold, RioBase Metals, RioChrome, RioDiamonds, and RioEnergy, owns and operates Murowa Diamonds, Cam and Motor Gold Mine, Renco Gold Mine, Dalny Gold Mine, Sengwa Colliery, and the Empress Nickel Refinery. Zimbabwe, like Rhodesia under the BSAC, is “open for business.”

In 2023, the Indian billionaire owner of RioZim, Harpal Randhawa, died in a plane crash just north of Murowa, Mazvihwa, in south-central Zimbabwe. The residents of Murowa said that the ancestors downed the plane in response to RioZim’s mistreatment of its workers and the land. As of January 2025, Murowa Diamonds workers were owed over three months in backpay, and 300 workers were engaged in an extended labor strike, evidence that Zimbabwe’s chimurenga spirit endures, and there may be hope for the bateleur eagle.

Within this same rough chronology of post-2000 Zimbabwe, the concept of chimurenga was assaulted from every direction. Now, virtually every political dead-end could be called a “Third Chimurenga.” Marthinus L. Daneel used the phrase to describe tree-planting combined with religious-cultural revival in the spirit of the Association of Zimbabwe Traditional Environmental Conservationists (AZTREC). Then President Robert Gabriel Mugabe referred to land reform in the early 2000s as the “Third Chimurenga.” The chaotic beauty of war-veteran- and peasant-led land reform (jambanja) may have looked like a new Chimurenga when Mugabe wrote this in 2001, but state-led land reform in the proceeding years was devoid of any ideology that could be equated with the two previous Chimurengas.

“Fast Track Land Reform” was rhetorically aimed at “white farmers,” not at colonial-era investor-owned land which posed a much larger threat to Zimbabwe’s future than the remnant white farmers. Gains were made: A Union Carbide–owned ranch near Zvishavane was resettled, one of two major parcels owned by De Beers was partially resettled, and jambanja activists resettled a small section of Austrian-Swiss-German-owned Border Timbers land in Chimanimani. In all three examples, the government turned their back on resettled families, which, coupled with the dearth of international aid in resettlement areas, made life in these places increasingly precarious. Small and abandoned mines made their way into the hands of elite and middle-class Zimbabweans, but in the same era, international capital reinvested in Zimbabwe’s colonial-era mines along the Great Dyke.

For example, beginning in 1993, South Africa–based Impala Platinum and Bermuda-based Aquarius bought out Union Carbide’s shares in the Mimosa platinum mine in Zvishavane, and Aquarius’ 50 percent shares were then bought by South Africa–based Sibanye-Stillwater in 2016; not resettlement but rearrangement of the international stakeholders. The foreign-owned diamond mine mentioned earlier, Murowa Diamonds, ceased operations and stopped paying their workers in 2024, despite producing approximately 1 million carats per year since 2004, after they evicted nearly 1,000 people to open the mine. These are but a few examples, a regional glimpse of a national phenomenon. The gains made during land reform have been offset ten-fold by shareholder-owned, non-Zimbabwean companies’ renewed commitment to carrying on the legacy of the BSAC.

Ranger recognized the hollowness of this deluge of Third Chimurengas, and instead he mockingly likened the Third Chimurenga to the ruling party’s bullying of the ascendent opposition party, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), in the early 2000s. When Ranger began ringing the alarm about the dangers of “Patriotic History” in his final decade, his warning was not directed only at the politics of ZANU-PF, nor was it in defense of the MDC. This dumbing of the past in “Patriotic History” produced a neoliberal political opposition just as tone-deaf as the ruling party, because opposition is not an ideology but merely a reaction. The MDC “[abandoned] liberation politics” as a reaction to ZANU-PF’s misuse of liberation history, which helps explain why both political parties supported Zimbabwe being wide open for investment and foreign ownership, and in continuing the legacy of the BSAC. The true Third Chimurenga will break from these two mirrored paths to reject the investors who plunder and poison the earth and who chased away the bateleur eagles. Those chapungu who will usher in the Third Chimurenga have yet to return, and until then, only the past can guide us.