Archiving pan-Africanism

A project - helmed by historians Benjamin Talton and Jean Allman - to archive post-independence African revolutions, including Kwame Nkrumah's personal and professional papers.

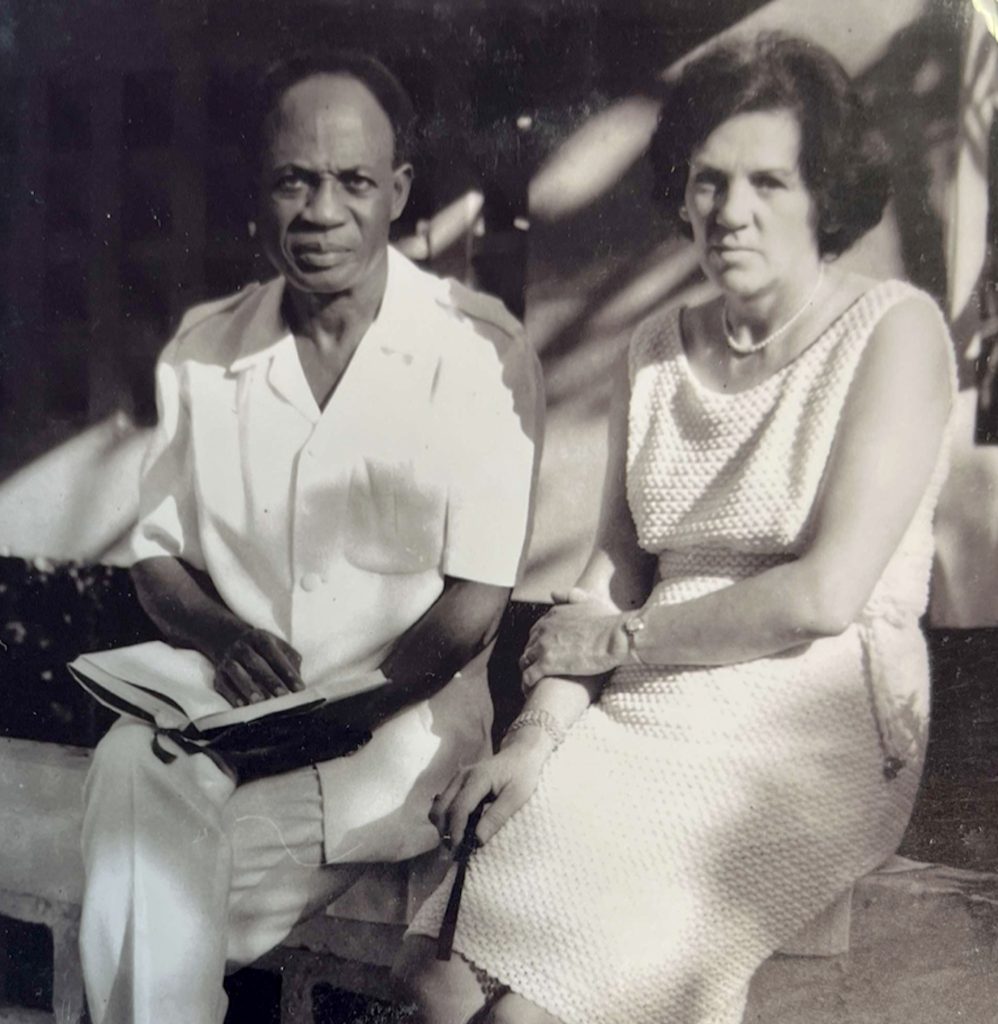

Stokely Carmichael, Kwame Nkrumah, and Shirley Graham DuBois 1967. Image courtesy of the Thabo Mbeki Foundation.

- Contributors

- Jean Allman (JA)

- Benjamin Talton (BT)

On February 24, 1966, a military coup d’état orchestrated by the police and the army overthrew Kwame Nkrumah. The event unfolded in Nkrumah’s absence, with the prior knowledge and approval, and likely the assistance, of the United States and Great Britain. The president was on a peace mission to bring an end to the brutal war in Vietnam.

The coup launched Ghana—Africa’s Black Star—into a quarter century of political instability. This included decades of anti-democratic rule, economic decline, and the World Bank and the IMF dictating draconian measures to liberalize the market. Many would argue that the nation still feels the aftershocks from that fateful day in February 1966.

Seldom discussed is one of the most enduring of those aftershocks: namely, the void in documentary evidence rendered by the illegal seizure of power. The military was relentless in its destruction of official documentation and the personal papers of Kwame Nkrumah. When the soldiers raided Flagstaff House, the site of Nkrumah’s office and residence, they were on a search-and-destroy mission. They seized soldiers loyal to Nkrumah in their determination to destroy anything and everything in their path. Most of Nkrumah’s papers, the records in his office, his notebooks, and his manuscript drafts in various forms of completion, did not survive that fateful day. As was done to the effects of other deposed African leaders, individuals and groups sought to destroy Nkrumah’s personal and political papers. Their deliberateness shows that a lot more than political power is lost in a coup d’état.

Anyone who has worked in Ghana’s public archives on the Nkrumah years, and especially on Nkrumah himself, knows firsthand about the documentary silences, the empty files, and the research trails long gone cold.

Of course, Nkrumah did not just disappear in 1966. While in exile in Conakry, he made regular broadcasts to the people of Ghana. He also began writing and publishing: The Challenge of the Congo, Class Struggle in Africa, Axioms of Kwame Nkrumah, Dark Days in Ghana, Revolutionary Path, The Rhodesia File, Voice from Conakry, and Handbook of Revolutionary Warfare, and several pamphlets. Each of these publications appeared after the coup and before his death in Bucharest in April 1972.

Despite Nkrumah’s prolific output of books and pamphlets, his political legacy slowly faded. The vagaries of African politics reduced Nkrumah’s vision of a politically united continent to an artifact of a bygone, far more optimistic age.

That began to change in the 1980s—a decade of political transformation in Africa.

Across the continent, and throughout the African Diaspora, neoliberalism and the austerity it enforced deferred economic and political innovation. Pan-Africanism, socialism, and people-centered development were largely confined to sloganeering. Still, the decade did not lack leaders and movements that strove to provide political-left alternatives. Many of them looked back to Nkrumah for inspiration in their critique of the geopolitical shift toward political and economic conservatism.

In December 1981 for example, Jerry John Rawlings’ second successful coup signaled the Black Star Nation’s return to revolutionary projects. In Grenada in the Caribbean, Maurice Bishop led the New Joint Endeavor for Welfare Movement, Education, and Liberation, or New Jewel Movement. By engaging in a bloodless revolution in 1979, Bishop successfully positioned his movement as the country’s ruling party. However, his five-year project ended with his own assassination in 1983. That same year, in Burkina Faso, Thomas Sankara embarked on a project to secure the country’s economic independence from France, its former colonizer, and to dismantle the debt trap set by Western financial institutions.

Throughout the 1980s in other words, optimism continued to flash in pockets of Africa and the diaspora. In the opening year of the next decade, Namibia raised its independent flag. Shortly thereafter, Nelson Mandela walked out of prison in South Africa and went on a six-week, 13-country speaking tour. The global anti-apartheid movement became the largest mass pan-African and human rights movement in history, which helped pave the way for democracy in South Africa.

For Nkrumah’s many friends and followers, the 1980s only evidenced the truth of his prediction further: the absence of African unity left an open door to European neocolonialism and structural dependency, creating poverty in African countries. Nkrumah’s words echoed across the years as a call to action, a call for continued struggle—a luta continua!

But why weren’t Nkrumah’s ideas relegated to the dustbin of history with his overthrow in 1966? How were they kept alive, nurtured, circulated, and repeatedly affirmed, even well after his death in 1972?

Among the most active custodians of Nkrumah’s legacy during the 1970s and 1980s was June Milne. Born in Australia in 1920, Milne was educated in Britain and trained as a historian. She lectured at the University College of the Gold Coast and in 1957 became Nkrumah’s editorial assistant. After the coup, when other publishers dropped Nkrumah from their lists, she started Panaf Books in 1968 to keep his works in print and to publish new ones on pan-Africanism. During the years of Nkrumah’s exile in Conakry, she visited him 16 times. She visited him three times in Bucharest, Romania, where he went for medical treatment in 1971, and was there with him when he died on April 27, 1972. Milne continued to run Panaf until she retired in 1987.

During the 1980s, Milne and her network of pan-Africanists, along with the friends and children of Kwame Nkrumah, preserved his legacy. Through conferences and publications, they strove to ensure that the memory of Ghana’s first president would not disappear into the dustbin of history. Milne herself took up the herculean task of gathering, retrieving, assembling, and organizing whatever she could of Nkrumah’s personal and professional papers. She began to build an archive.

It was June Milne who donated most of the Nkrumah Papers to Howard University’s Moorland-Spingarn Research Center (MSRC) in 1984. She traveled to the campus in Washington, DC to officially deposit what she then had at hand. Shortly after, in 1986, she traveled to Conakry and managed to retrieve an additional cache of Nkrumah’s papers and books from Villa Syli, Nkrumah’s home during his Conakry years. She brought this “Conakry Archive” to Howard in 1987. And in 1989, she rounded out these collections with 62 books and administrative files for Panaf.

The bulk of the Nkrumah papers at Howard covers the years 1965-1974. The collection brings together a significant number of letters and cables exchanged between Nkrumah and his acquaintances, friends, and staff. It assembles communications that were made toward the end of Nkrumah’s presidency and during his years at Villa Syli. The correspondence illuminates the circle of personalities orbiting near Nkrumah. To name a few, these included W.E.B. DuBois, Shirley Graham DuBois, Marvin Wachman (then president of Lincoln University, Nkrumah’s alma mater); social justice activists Grace and James Boggs, and Julia Wright, writer, and daughter of Richard Wright. Many others can be identified in the hundreds of files of correspondence found in the collection.

The Nkrumah collection at Howard is essential to any study of pan-Africanism and nation-building in the Africa of the 1960s and 1970s.

Enter two historians: Jean Allman and Benjamin Talton.

I have been working on Ghana’s postcolonial history, particularly on Nkrumah’s Ghana, for many decades. In the early 2000s, as my focus tightened on Nkrumah and the First Republic (1960-66), I spent time with the Howard collection and was surprised to see how much material Milne had been able to amass, including from Villa Syli in Conakry. I was also intrigued by the fact that Nkrumah’s letters to Milne were not included in the Howard collection.

Over the years, I made efforts to contact Milne, who was then in her 90s, but without success. Then, I learned in May of 2018 that Milne had passed away at the age of 98. Almost two years later, I came across an article in The New African, which described the wayward journey that had brought the remaining papers in the Milne papers from Norwich, England, to the Harare-based Institute of African Knowledge, and then to the Thabo Mbeki Foundation, as a deposit for the new Thabo Mbeki Presidential Library and Centre.

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when everyone across the globe was trapped in their houses, I regularly sent out emails to try and figure out where precisely the papers had ended up, if they were being preserved, and if, in fact, they were accessible.

The big breakthrough came in June of 2022, when Blessing Mawire, the Project Manager for Content, Programs, and Internationalization at the Thabo Mbeki Foundation (TMF), responded to my email. “Yes, the papers are in South Africa and the first inventory of their contents was just being completed.”

I immediately invited Mawire and Talton, and several others, to participate in a panel in October, at the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ghana on “The Archival Diaspora: In Search of Ghana’s Postcolonial Past.” It was there that Talton and Mawire began to talk about ways they might collaborate, in order to bring the two parts of Milne’s collections together and to digitize them so they would be globally available.

In late February, exactly 57 years after Nkrumah’s overthrow, all three of us reconvened at the National Library of South Africa (NLSA) in Pretoria, where the Thabo Mbeki Foundation has collaborated with the NLSA for the preservation and conservation of the collection, and to uncover just what Milne had held on to in the decades since she deposited that first batch of Nkrumah material at Howard.

At NLSA, we were granted full access to the papers and discovered that the collection was clearly related to, but distinct from, the files Milne had deposited at Howard almost 40 years earlier.

While Nkrumah is the key subject and organizing focus of the papers, Milne is very much present as editor, confidante, and archivist. With every box, we confronted new revelations through Milne’s own highly active correspondence via letters and telegrams with Nkrumah and those who had been his associates, staff, close friends, and members of his family. Milne, for example, maintained a fascinating, often fraught, but enduring friendship with Julia Wright, the daughter of writer Richard Wright. Milne’s deep and sustained connections with Gamal Nkrumah, Nkrumah’s son, are palpable in her letters to Wright and Fathia, Nkrumah’s widow.

For me, what was most edifying were the detailed records that chart the journey of Nkrumah’s papers from Villa Syli to Howard University. There are files that include correspondence between Milne and MSRC’s staff, particularly Robert Battle, head of the center’s Manuscript Division. The letters provide a surprisingly detailed narrative of June Milne’s early plans for Nkrumah’s papers, MSRC staff’s effort to prepare to house them at Howard, and her two visits to the university. Her letters also reveal that she aspired for the Kwame Nkrumah Collection to be the centerpiece of a Kwame Nkrumah Institute at Howard that would be the world’s premiere center for the study of pan-Africanism.

Highlights, for me, include the long and frequent letters (two to three per week) from Nkrumah to Milne, beginning some two weeks after the coup and ending shortly before his death in Budapest. The topics range from the pamphlets and books he was working on to his health; from the situation in Ghana to the state of pan-Africanism; from the nature of revolutionary warfare to his affection for Milne. The only stretches of time in Conakry not covered in Nkrumah’s letters, are those 16 times when Milne was in Conakry with him. And those periods are carefully documented in her 16 Conakry travel diaries, and the three diaries from her visits to Bucharest. This part of the collection provides unparalleled insight into Nkrumah’s unfolding perspectives on neocolonialism, marriage, capitalism, racism, the global Black Freedom Struggle, and revolutionary violence, as well as the rhythm and substance of his daily life.

The nearly 30 boxes of materials amassed by Milne over more than five decades constitute a significant addition to the archives of the African Revolution and its afterlives, and include not just letters, but photographs, various drafts of Nkrumah’s manuscripts, magazines, newspapers, Panaf files, and LPs. My goal, as MSRC director, in partnership with the TMF, is to ensure unencumbered public access to these extraordinary collections. Toward that end, our collaborative goal is to fully digitize the collections at Howard and the TMF, so that scholars and activists from across the globe, but especially in Ghana, will finally have access to these collections.

For both of us, our brief peek at the collection being processed by the TMF has only affirmed that Nkrumah is no less relevant to struggles for freedom and justice today than he was in the 1950s and 60s or in the 1980s. Thanks to June Milne’s devotion to Nkrumah’s Pan-African vision and her painstaking work over so many decades, not only as his editor and literary executor, but as the diligent archivist of his past, present, and future, Nkrumah lives on. Viva!

My research on the political events, individuals, and issues that defined the 1980s as a distinct historical period, initially did not include Kwame Nkrumah. It appeared to me that the continent, and the African diaspora, had turned in an entirely different political direction by the late 1970s, and Nkrumah was a name to recall within the pantheon of African political icons. But Nkrumah lacked a living legacy. My conception of Nkrumah’s legacy within the 1980s (what a small, but growing group of colleagues refer to as the “Black 1980s”), changed after I explored Howard University’s rich and unique collection of Kwame Nkrumah’s personal and professional papers housed at MSRC, where I assumed the role of director in January 2022.