God tax the king

The British royal family has tried to shake off its colonial past. But its long reign over these wrongs was succeeded by a new form of plunder, exacted today by Britain’s tax haven empire.

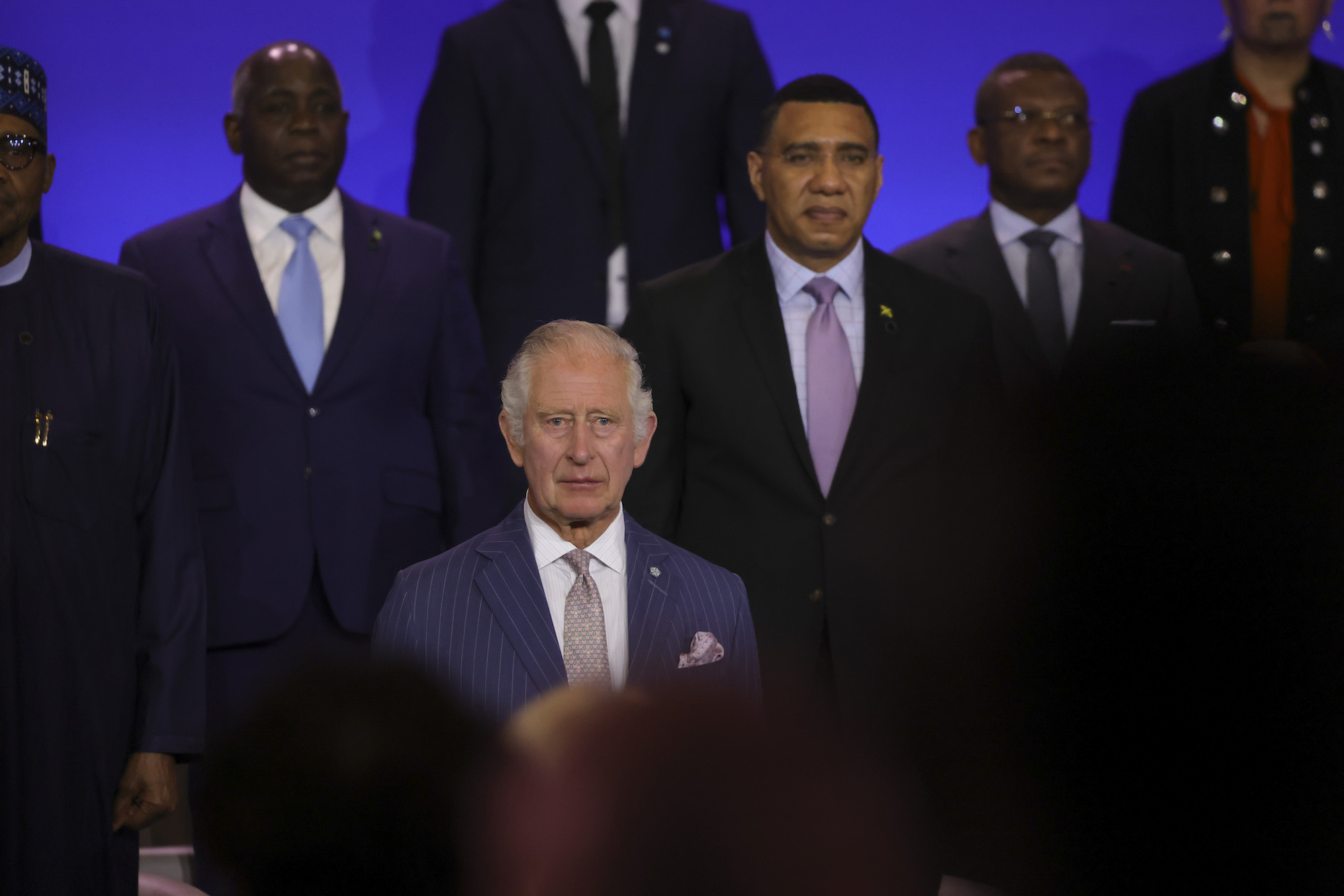

Prince Charles in Kigali, Rwanda. Image credit Simon Dawson for No. 10 Downing Street via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

The world’s biggest tax haven empire has a new king. King Charles III will be anointed, blessed, and consecrated on May 6. He is sovereign over Great Britain, the Crown Dependencies, and the British Overseas Territories, which collectively inflict nearly 40 percent of the tax revenue losses around the world.

Britain was starting to spin its web of tax havens around the time Charles was born in the late 1940s. Britain allowed and often encouraged this insidious second empire as many nations were breaking from the shackles of European and British colonialism. Currently, British tax havens aid and abet multinational corporations shifting profits out of the countries where most of the real business happens. Wealthy and powerful individuals are also able to hide money and assets behind the secretive laws of the spider’s web.

The Tax Justice Network—a coalition of activists, and scholars campaigning against tax avoidance—sent an open letter to King Charles urging the monarch to address the economic and human cost imposed by the British tax havens over which he is sovereign. The letter details the organization’s latest research which estimates that British tax havens mete out a total tax loss of more than US$189 billion per year on the world. The total tax losses are more than three times the humanitarian aid budget the UN needs this year to help 230 million people living on the brink after multiple disasters.

While Britain’s overseas aid has dwindled in recent years, unwinding the web of tax havens instead would help many governments fulfill the rights of their citizens. If we were to reverse the tax revenue losses caused by the UK spider’s web, there would be 36 million more people with access to basic sanitation, 18 million more people with access to basic drinking water, and almost seven million children could attend school for an extra year, according to the Universities of St. Andrews and Leicester modeling tool GRADE.

Yet, the British political establishment doesn’t look ready to reform. Successive Conservative prime ministers and their families have been fingered in leaks and investigations, including the Panama and Pandora Papers. The wife of current British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak also played the tax game, avoiding an estimated £2.1 million per year in taxes from foreign income.

The British government has also undermined efforts to transform international tax law. For the last 60 years, the UK—along with the exclusive club of the richest nations at the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)—has set rules to their benefit. African states, in an act of defiance, presented a resolution at the United Nations in November 2022 that paves the way for negotiations on an international tax cooperation framework at the UN instead. The UK and its OECD friends unsuccessfully pulled out all the stops to prevent a vote, and spoke out against the resolution, but ultimately joined in its unanimous adoption. They will likely throw many hurdles in the way to stop negotiations from getting off the ground at the UN General Assembly later this year, as their initial input to the Secretary-General’s Tax Report makes clear.

In his speech to the Commonwealth Heads of Government in Rwanda last year, King Charles, then Prince of Wales, expressed his sorrow over Britain’s “most painful period of history.” “To unlock the power of our common future,” he said, “we must also acknowledge the wrongs which have shaped our past.”

The British royalty’s long reign over these wrongs was succeeded by a new form of plunder, exacted today by Britain’s tax haven empire. King Charles has an opportunity to stop the clock running on this plunder. As the inheritor of the British Crown and its legacy, King Charles could use his unique position to encourage dialogue on UN leadership over international tax rules—a move that could pivot the course and legacies of history—and support the right of African countries to exercise sovereignty over their taxing rights at the UN General Assembly.

At home, the King might rightly argue that he has no business interfering in the UK government’s policies. It may be His Majesty’s Government, but it’s a democratically elected government of its people. We should not expect Charles to outline his positions on the need for the UK finally to meet its commitments to end anonymous companies that make it too easy for criminals and would-be tax evaders to hide assets and illicit money, or to introduce public country-by-country reporting so that multinational companies’ tax abuse remains largely out of sight. In the UK, the reporting would have increased corporate income tax by £2.5 billion per year.

What we can hope for, however, is that the new King will set the tone for the end of his tax haven empire. By acknowledging publicly Britain’s leading global role in tax abuse, and the human costs this imposes all around the world, Charles could make a necessary break from the history of imperial and royal denial. He could point the way to reparative funding for territories that make up the tax haven empire, as well as to those countries in Africa and elsewhere where the empire’s most violent extraction took place.

Extensive slavery routes and sanctioned colonial pillaging all added jewels to the crown over centuries, some of which make appearances at coronations. King Charles himself also has some questionable wealth and tax practices. Without changes in its tax havens and the global tax rules, Britain will continue to rack up its bill of reparations to former colonies.