Milk in the Upington sun

Fear of the future, longing for the past: the new story in South African politics.

President Cyril Ramaphosa. Image credit GCIS via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0.

For Pakistani-born author Mohsin Hamid, pessimism almost naturally precedes regressive and right-wing movements because when we become incapable of seeing progress in terms of reaching our political destination, we naturally look to our past for safety and comfort. The past, therefore, becomes an item of nostalgia. From ISIS trying to reinstate a Muslim Caliphate to Donald Trump trying to make America great again, to the Brexit campaign trying to imagine a pre-migrant Britain. All of these regressive movements are driven by some kind of frustration with the present, a pessimism concerning the future, and a subsequent move to recreate the past.

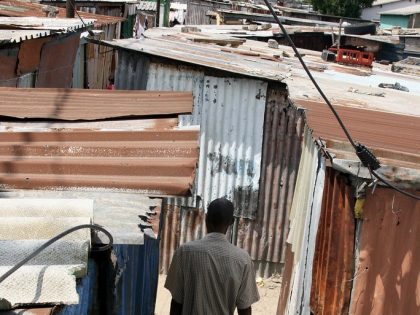

Contemporary South Africa, in my view, reflects this growing sense of pessimism and ensuing attraction to regressive forms of politics seen across the world. Economic hardships, violent crime, ineffective, corrupt governance, and persistent poverty and inequality have frustrated our ability to formulate optimistic visions of the future. The now old catchphrases of 1994 such as “Rainbow Nation” and “New South Africa” seem not to carry as much weight as they once did. These phrases are instead being regularly questioned and even mocked. Later iterations of South African feel-good catchphrases, such as President Ramaphosa’s “New Dawn” slogan seem to have expired quicker than milk in the Upington sun.

The New Dawn has struggled to overcome poor electoral performance by the ANC and a seeming inability of Ramaphosa’s government to follow through on many of the goals they set for the country. A deep sense of disappointment has set in the national mood. This disappointment however, extends beyond our lackluster government. Indeed, much disappointment stems from our deep guilt as a society: our inability to protect women and children; our inability to overcome our everyday interracial conflicts; and our inability to build credible opposition movements. These are just a few examples of situations in which I feel many of us subconsciously have a deep sense of guilt and subsequently have offered ourselves over to general pessimism.

Many South Africans seem to have given up on trying to find our destination and are now invested in heading back to some version of the past. This is not to say there’s unity among the pessimists. Versions of the past differ greatly and so do the actual periods of the past that different pessimists wish to recreate. Notable examples of pessimistic movements are the likes of Operation Dudula, which seeks to reverse migration trends to a time when the numbers of African migrants in South Africa were far fewer. Another example is the rightward shift of the Democratic Alliance (DA) towards a purer interpretation of traditional liberal principles. Several factors have led to this and pessimism in my view is one. At some point, the DA seriously pursued the goal of being an inclusive political party. That pursuit has led them down a rocky path that many within the party seemingly abandoned. Numerous other civic organizations have also sprung up seeking to promote some kind of reversal of current trends. Gatvol Capetonian has sought to reverse demographic trends in the Western Cape. The CapeXit movement promotes a pre-1994, pre-Apartheid vision where Pretoria had far less influence over the affairs of the Cape. Neither Gatvol nor CapeXit has seen widespread growth in support, however their methods of fetishising the past seem to be shared by many other social movements.

It is therefore critical that we understand the dangers of pessimism. We need to see it as more than just a frustrated state of mind in relation to government. Political pessimism is very often a gateway to further regressive and reactionary politics. It is also extremely manipulatable, South Africa has a long list of charismatic pessimists who peddle cynicism and fear in order to ride the wave of negative emotions that emerge. These characters pursue their interests without much regard for human well-being or even life. Therefore I believe that in defense of societal stability we should take care to ground our social movements in optimistic visions of the future.

These visions should not be confused with utopias that are detached from reality, but rather as attempts at viewing our current circumstances in terms of growth opportunities, instead of only seeing threats. For instance, what could be gained from greater cooperation with our regional neighbors instead of fearing that their nationals seek only to plunder what little we have? Others might ask what lies beyond the rigid patriarchal demands that so many in South African society passionately defend. Many have already begun grappling with how a shift to renewable energy could create a more just and inclusive society.

In the end, it will be the specifics that determine how successful these visions can be. One thing is certain though, the longer we fail to imagine an optimistic future, the more we will seek shelter in the dark past.