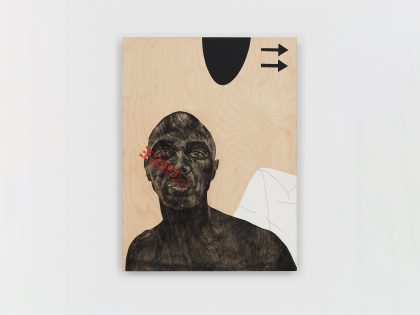

The Upright Man, Thomas Sankara

Burkina Faso is finally beginning to do right by the memory of revuolutionary leader, Thomas Sankara.

Soldier in Burkina Faso. Image credit C. Hugues via Flickr CC.

This month, a foundation in Sankara’s name, unveiled plans for a public memorial. This happens nearly 29 years ago this month after he was murdered and two years since Blaise Compaoré–considered one of the key people responsible for Sankara’s murder– fled the country.

Throughout this time, Sankara remained an inspiration to young Africans and people committed to a radical pan-Africanist future. His supporters and admirers argue that his short four-year reign as President of Burkina Faso from 1983 to 1987 – for all its faults – pointed briefly to the potential of different political futures for Africans, beyond dependency, neocolonialism and false dawns of “Africa Rising.”

Plans for the memorial and a museum were announced at a symposium in Ouagadougou held in Sankara’s honor and attended by nearly 3,000 people. As the BBC reports: “The proposed memorial is estimated to cost around $8m (£6.2m) and will be funded by small contributions from supporters of the former Burkinabe president.”

On October 15, 1987, armed men burst into the office of Sankara, murdered him and twelve of his aides in a violent coup d’état. In events that eerily paralleled those in the Congo 27 years earlier (when a conspiracy of European intelligence agencies and their Congolese surrogates murdered Patrice Lumumba), the attackers cut up Sankara’s body and buried his remains in a hastily prepared grave. The next day Compaoré, who was Sankara’s deputy, declared himself president. Compaoré then went on to rule the country until 2014, when he was forced to flee the country amidst a popular uprising. Between 1987 and 2014, Compaoré both attempted to co-opt and distort Sankara’s memory and making promises to bring his murderers to justice. Nothing ever came of that.

Burkina Faso (known as Upper Volta until 1984) didn’t attract much attention outside West Africa until Sankara overthrew the country’s corrupt and nondescript military leadership in 1983. (It bears repeating that Burkina Faso had been ruled by military dictatorships for at least 44 years of its independence from France. The military before Sankara basically acted as surrogates for French interests in the region. One year after Compaore fled, there was a brief one week coup, but the country has been ruled by democrats and figuring out a new constitution since then.)

Like Lumumba – an earlier principled political leader who was a violent casualty of the Cold War – Sankara proved to be a creative and unconventional politician. He wanted to a chart a “third way,” separate from the interests of the major powers (in his case, France, the Soviet Union and the United States). This, however, resulted in a complex legacy where those who praise his social and economic reforms — discussed below — have a hard time squaring it with his often-undemocratic politics.

In 1985, Sankara said of his political philosophy: “You cannot carry out fundamental change without a certain amount of madness. In this case, it comes from nonconformity, the courage to turn your back on the old formulas, the courage to invent the future. It took the madmen of yesterday for us to be able to act with extreme clarity today. I want to be one of those madmen. We must dare to invent the future.”

The documentary film, Thomas Sankara: the Upright Man by the British filmmaker Robin Shuffield, is probably the best filmic account of Sankara’s rise, governing style, reforms and his eventual murder. It also gives some sense as to why–unlike say Lumumba among Third World nationals or Nelson Mandela among Western elites–people beyond West Africa (and now with students in South Africa) don’t mention Sankara much these days (except for those with more than a passing knowledge of postcolonial African politics).

Sankara openly challenged both French hegemony in West Africa as well as his fellow military leaders (Sankara labelled them “criminals in power”). He called for the scrapping of Africa’s debt to international banks, as well as to their former colonial masters. Check the many clips of him doing just that at public events in Harlem, New York or Addis Ababa.

His reforms were widespread, both at a symbolic level and in terms of political and economic reforms. For one, in 1984 he changed the country’s name from Upper Volta, the name it kept from colonialism, to Burkina Faso. The country’s new name translates as “the land of the upright people.”

Sankara preached economic self-reliance. He shunned World Bank loans and promoted local food and textile production. (There’s a classic scene in Shuffield’s documentary where he had the whole Burkina delegation to an Organization of African Unity meeting decked out in local textiles and designs.)

Sankara outlawed tribute payments and obligatory labour to village chiefs, abolished rural poll taxes, instituted a massive immunization program, built railways and kick-started public housing construction. His administration aggressively pushed literacy programs, tackled river blindness and embarked on an anti-corruption drive in the civil service.

Women, the poor and the country’s peasantry benefited mostly from these reforms. His administration promoted gender equality in a very male-dominated society (including outlawing female circumcision and polygamy). As Sankara told a local audience in 1984: “Socially, [women] are relegated to third place, after the man and the child — just like the Third World, arbitrarily held back, the better to be dominated and exploited.”

He discouraged the luxuries that came with government office and encouraged others to do the same. He earned a small salary ($450 a month), refused to have his picture displayed in public buildings, and forbade the uses of chauffeur-driven Mercedes and first class airline tickets by his ministers and senior civil servants.

But Sankara’s regime was not immune to undemocratic practices.

He banned trade unions and political parties, and put down protests (most significantly one by teachers in 1986). Many people were the victims of summary judgments by people’s revolutionary tribunals, which sentenced “lazy workers,” “counter-revolutionaries” and corrupt officials. Sankara himself would later admit on camera that the tribunals were often used as occasions to settle private scores.

By 1987, he was politically isolated. His enemies – a mix of the French political establishment (he had humiliated President François Mitterand in public on a few occasions) and regional leaders (like Ivorian President Félix Houphouët-Boigny) – began to tire of him.

Compaoré is widely suspected to have ordered Sankara’s murder in order to do the French and regional dictators a favor. Though Compaoré pretended to publicly grieve for Sankara and promised to preserve his legacy, he quickly set about purging the government of Sankara supporters.

In contrast to the cool reception given Sankara earlier, Compaoré was welcomed by Western governments and funding agencies. Within three years, Compaoré had accepted a massive IMF loan and instituted a structural adjustment program (largely seen as one of the major causes for the ongoing economic crises in Africa). Compaoré also reversed most of Sankara’s reforms. Not surprisingly this included the insistence that his portrait hang in all public places as well as buying himself a presidential jet.

While he was in power, Compaoré proved reluctant to investigate Sankara’s death fully. His government wanted to “move on.” Compaoré – whose regime had been implicated in the civil wars in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Cote d’Ivoire and Liberia – even tried a makeover as a “democrat” (he won a series of elections in the 1990s and 2000s), and was a key ally of the US.

After Compaoré fled the country in 2014, he, along with fourteen senior army officers, were indicted for their role in Sankara’s murder. However, the case has stalled.

As Mathilde Monpetit wrote on AIAC in July 2015, Sankara was a key inspiration of anti-Compaore protesters, some even identifying as “Génération Sankara.” But Monpetit wondered aloud about the renewed interest in the liberation politics that Sankara represented; “Is this renewed interest indicative of a revived interest in socialism, or simply the grasping of a people looking for a leader after the end of a political era? Sankara may simply stay the Che Guevara of Burkina Faso, in death representing an image of Burkinabè anti-colonial discontent that need not be compatible with the actions or ideology of the people who put his image on their shirts and walls.”

This weekend’s symposium, however, suggested that Sankara remains a real presence for social movements (and some governments) in Africa. Present were, for example, were activists of Balai citoyen, the citizen movement which played a role in the 2014 uprising in Burkina Faso, as well as Fidel Barro, one of the leaders of Senegal’s Y’en a Marre. Burkina Faso’s cultural minister told the audience: “Those who killed Thomas Sankara simply cut the tree, forgetting the roots. Now, we all know, the strength of the Baobab is based in its roots. Whatever they did, Thomas Sankara remains alive forever.” The foundation building the memorial and the museum insists, however, that it be build by the people and not the state.

The last word goes to Barre told an AFP reporter: “There is a Sankara for economics, a cultural Sankara, an avant-garde Sankara, a Sankara for the democratization of [political] power, a Sankara for the freedom of expression and speech. It is all these Sankara that these youth have come to admire because they want that Africa moves forward. They need that Africa becomes independent. Sankara goes beyond Burkina Faso, he is an African and World treasure.”

- This post draws on a piece I wrote for The Guardian in October 2008 as well as reference a number of posts written on Burkina Faso on this site.