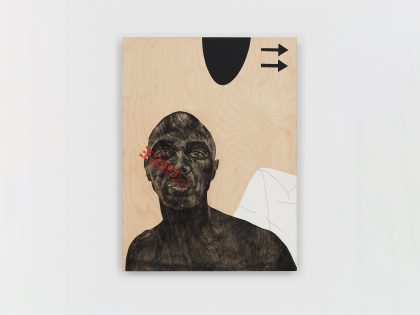

The Rape of Africa

Celebrity photographer David LaChapelle chose Naomi Campbell to represent how Africa is raped for its resources. Did it work?

A relief from "Critique of a global society fuelled by greed …" A detail from David LaChapelle's "The Rape of Africa."

David LaChapelle, he of the gaudy photography and expensive music videos, has a new show, “The Rape of Africa,” running in London. We are told, it is “an angry political statement,” by The Independent. The show is ” a tribute to Botticelli’s painting ‘Venus and Mars’.” The point is to announce him as a “serious artist”: “…On a personal level it announces LaChapelle as no longer a celebrity snapper, but an important contemporary artist more than capable of bringing intellectual and historical weight to his art,” observes The Independent’s Fiona Sturges. One image has gotten a lot of attention. In it, the supermodel Naomi Campbell is Venus, the goddess of love. On the right, a white male model as Mars lies sleeping. Behind them are scenes of war. “The couple are flanked by children, two of whom carry machine-guns.” Sturges concludes, “the ravaged backdrop, the armed children and the piles of gold point to a land and a culture destroyed by global consumerism, notably the gold and diamond industries, and war. Meanwhile Campbell, in all her exotic finery, represents the objectification of African women, by Western culture, as their homes and countries are torn apart.”

Sturges goes onto note that reactions to the image have been largely positive, but LaChapelle tells her everyone doesn’t approve: “One critic said that having Naomi Campbell sitting there looking beautiful wasn’t an honest representation of people in Africa.” LaChappelle tells Sturges:

I asked him: ‘If it was a woman with a distended belly and open sores, would that be more profound for you?’ We see those images every day, on the TV and in newspapers. I have this idea that you can use glamour and still have it represent something that matters. I believe in a visual language that should be as strong as the written word. It’s following the same idea as murals where you have a series of narrative pictures. They are telling stories and communicating with people, which is always what I have set out to do.”

The sense you get from the article is we are now meant to take him (more) seriously.

I appreciate (pop) culture, especially the ways in which it intersects with politics in and on Africa, more than the next person, but David LaChapelle somehow doesn’t seem to be the right person for this job. Of course, “this job” is routinely taken up by many North American and Europeans artists, celebrities, and the like. All one needs to do to stay relevant is say something “meaningful” about Africa.

The show runs until 25 May at the Robilant + Voena gallery in London.

- To be fair, I did enjoy his 2005 film, Rize.