What former Chadian dictator Hissène Habré’s July trial in Senegal means for his victims

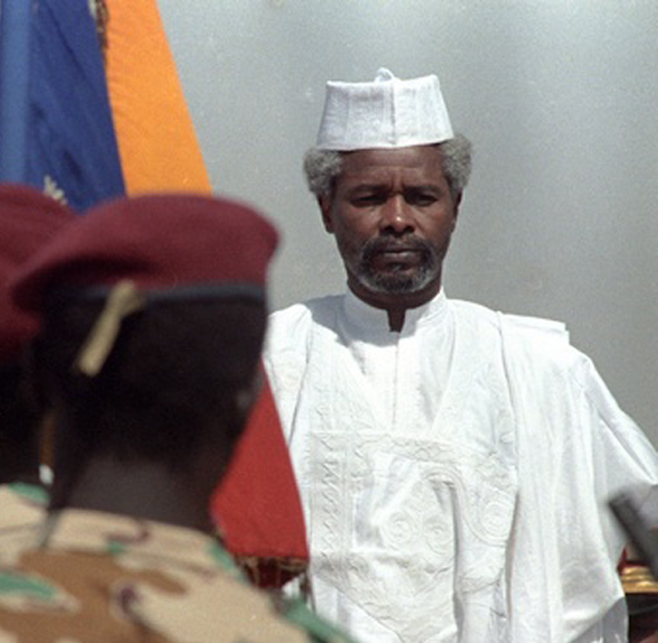

Pope John Paul II and Chadian President Hissene Habre (R) listen to the National Anthem during the departure ceremony at N'Djamena Airport February 1, 1990. The Pope ended a three-day visit to Chad, the last stop of his African tour.

Next month former president Hissène Habré, who ruled my native Chad from June 7, 1982 to December 1, 1990, goes on trial in Senegal, in a special tribunal set up by the African Union. Habré’s reign was one of absolute terror. He created the Documentation and Security Directorate (DDS), which quickly developed into a machine of repression. According to the report of an investigation ordered by the Chadian government in 1992, 40,000 people were killed in the prisons of the DDS.

As Human Rights Watch reminds us, “Habré’s trial will be the first in which the courts of one country prosecute the former ruler of another for alleged human rights crimes. It will also be the first universal jurisdiction case to proceed to trial in Africa.”

Habré lives in exile in Senegal after he fled there following a coup d’etat by the current president, Idriss Deby Itno. In February 2000, we decided to file charges against Habré before the Senegalese judiciary.

Ever since October 2000—nearly 15 years ago—we had engaged the Cabinet of the First Investigating Magistrate in Chad by handing him 57 charges and a collective complaint against the principal collaborators and accomplices of Hissène Habré, citing them by name.

The two proceedings, in Senegal and Chad, were a long, hard battle. In Senegal, the former President Abdoulaye Wade not only did not want Habré to be prosecuted, but also refused to extradite him to Belgium so that he could be tried there, even as Belgium made repeated requests to extradite him. In Chad, the courts offered no response to our numerous efforts at bringing the henchmen of the former dictator to trial.

The election of the current president, Macky Sall changed things Negotiations between Senegal and the African Union were sealed with an agreement enabling the creation of the Extraordinary African Chambers (EAC), which provide for a court of an international character but operating under Senegalese jurisdiction. (The case will be heard by a Burkinabe judge along with two senior Senegalese judges.)

The Chambers were tasked with trying Habré and all people who committed crimes during his rule.

The investigating magistrates of the Extraordinary African Chambers carried out 4 investigatory commissions in Chad in the course of the investigation of victims’ complaints. Their work was recently completed and they issued a referral order before the criminal court of the EAC. We are waiting to find ourselves very soon face to face with Hissene Habré before the court.

For those of us who are from Chad, this is the end of a nightmare, because for more than 20 years we have been rubbing shoulders daily with our torturers without having the slightest certainty that they would be prosecuted, as many of them still occupy influential positions, making them very dangerous both for the victims and for those who accompany them. Many victims have also died without receiving any form of justice. It is a great victory because our persistence and determination have been vindicated: 20 accomplices of Habré were handed sentences ranging from 5 years to life in prison. It’s a great lesson for all those who continue to blindly persecute their people. Impunity no longer has its place in Chad.

I strongly believe in fighting against injustice and I firmly believe that these men and women that I am defending must have been imbued with the same feeling during this 20-year quest for justice. They felt abandoned by their country, Chad, which never recognized their status as victims, nor issued a public apology.

When I found myself facing Habré, alongside two victims and in front of the investigating magistrates for a confrontational hearing, I took full measure of my role as giving a voice to these innumerable people who do not have one.

For me, and, I believe, for many other human rights defenders, impunity is the principal cause of human rights violations. I am convinced that the trial of Hissène Habré will be a turning point for justice in Africa, and this trial will guarantee a final end to these massive and continuous violations in Chad. It will help to ensure that leaders of other African countries stop exterminating and start respecting the people they govern.

* For more on this case, see also previous posts on AIAC: here and here